Water for the environment and for people

Stanford researchers are compiling best practices and forward solutions to ensure enough water is available for both sustaining natural systems and meeting people's needs.

Stanford researchers are compiling best practices and forward solutions to ensure enough water is available for both sustaining natural systems and meeting people's needs.

Carving its way through the Grand Canyon, the mighty Colorado River has long been a symbol of the American West's unbounded wilderness. In reality, the river is heavily engineered, managed and used. It peters out before reaching its delta. In most years, users' water rights – the amount they are entitled to by law – actually outstrip the amount of water available.

"That catastrophe replays itself on a smaller scale all across the West," said Leon Szeptycki, executive director of Stanford's Water in the West Program, a joint program of the Stanford Woods Institute for the Environment and the Bill Lane Center for the American West. "It was built into the legal system that if water flows downstream and you lose control of it, it's a waste of water."

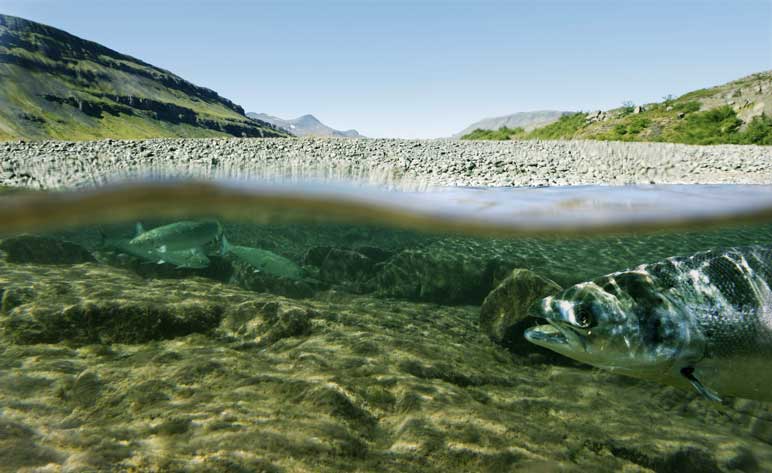

The use-it-or-lose-it ethos is compounded by growing populations, a changing climate and widespread drought. Among the biggest losers: fish and ecosystems dependent on stream and river flows. Current safeguards, such as the federal Endangered Species Act, mandate reductions in water diversions at the cost of intensifying the perception that water reserved for the environment comes at the expense of water for users such as farmers and city dwellers.

Colorado River viewed from Parker Dam

Underwater view of Salmon River in Idaho

137 threatened or endangered fish species in the U.S.

Now a group at Stanford is working to address the problem in a way that meets both environmental and human needs.

As part of a Stanford Law School practicum that Szeptycki taught in partnership with the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation (NFWF), student researchers have drafted a report that synthesizes best practices into recommendations for increasing the number of water rights transfers to maintain healthy flows for ecosystems. The report is due out later this spring. Elizabeth Hook, a law student who worked on the project, summarized the findings: "Just provide the largest tool-kit for deal-making that you can, with clarity and streamlining of administration at all levels."

Among the upcoming report's findings:

Specifically, the report suggests states institute five promising legal tools:

"No state is the same," said Kori Lorick, another law student who contributed research. "Each state has different stakeholders and different priorities – what works for one may not work for another."