Charles ‘Chuck’ Baxter, expert in marine ecology and co-founder of the Monterey Bay Aquarium, has died

A biologist’s biologist, Baxter was a continual presence in Stanford’s marine sciences and on the Monterey Peninsula for 60 years.

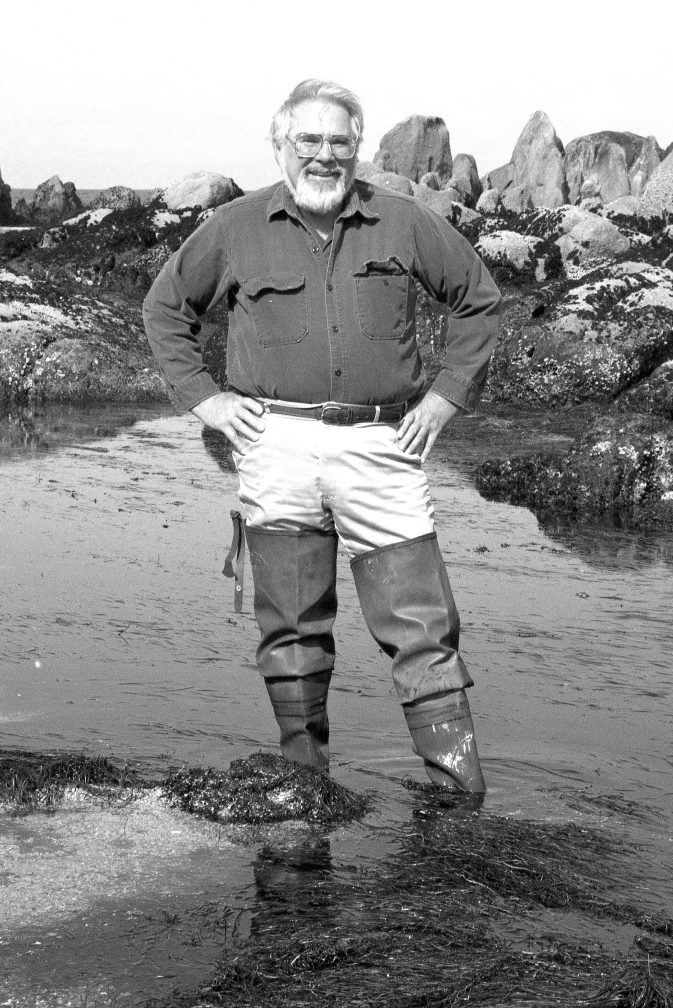

Charles “Chuck” Baxter, 1927–2022 (Image credit: Susan Harris)

Charles “Chuck” Baxter, an expert in marine ecology, a long-time lecturer at Stanford University’s Hopkins Marine Station, and a co-founder of the Monterey Bay Aquarium, died Aug. 19 at Community Hospital of the Monterey Peninsula surrounded by family. The cause was cancer. Baxter was 94 years old.

For more than three decades, Baxter was a fixture in the Stanford Department of Biology and at Hopkins Marine Station in Pacific Grove, California, lecturing and leading research efforts between 1961 and 1993, when he retired. His classes focused on the structure and function of animals, their evolution and ecology, and their influence on humans – and vice versa.

Baxter was a true field biologist who spent innumerable hours in the water turning rocks and counting and cataloging the species he found. A study he led in the 1990s noted the changing character of the species of Monterey Bay in the six decades since a similar study by Willis Hewatt in the 1930s. In the latter study, Baxter and co-authors charted an increase in “southern” species more accustomed to warmer waters, as well as a concomitant decrease in “northern” cold-water species. The researchers tied the differences to climate change.

“Chuck changed my life and my career. He introduced me to the flora and fauna of the intertidal. I fell in love with the diversity of life that live on rocky shores,” remembered Sarah Gilman, a professor of biology at Claremont McKenna College who worked with Baxter on that key study. “Chuck inspired me to think deeply about the species I study. He was an instigator. Big things just seemed to happen when he was around – like the Monterey Bay Aquarium or MBARI research institute. But he was never in the spotlight. I will always remember him in the field – hip boots halfway up, turning over a rock to look at the multitudes underneath.”

Deep dives

Charles Harold Baxter was born in Santa Monica, California, on Dec. 20, 1927. He grew up in Washington state. Baxter attended Santa Monica City College briefly before being drafted into the Army at the tail end of World War II. He then transferred to UCLA to study engineering. During a money-earning hiatus delaying what would have been his senior year, Baxter went diving off the breakwater at Venice, California. It was a life-changing experience. Picking up the book Between Pacific Tides by noted Monterey-based marine biologist Ed “Doc” Ricketts as his guide, Baxter’s career began a new trajectory. He returned to UCLA to earn his bachelor’s and master’s degrees in zoology.

“My courses in biology were fascinating, and I had gone from being a rather average student in engineering to trying to hit the top scores on the exams and impress all of my professors with my dedication and interest,” he recounted in an oral history recorded for the Stanford Historical Society.

He began lecturing at Stanford in 1961, working frequently at the Hopkins Marine Station on the Monterey peninsula. Baxter relocated permanently to Carmel in 1974 and taught at Hopkins until 1993. That year, he received the Lloyd W. Dinkelspiel Award from Stanford, the university’s highest recognition of undergraduate teaching, for inspiring students with “the joy of discovery and research in marine sciences.” The concept of retirement, to Baxter, seemed open to interpretation and he continued to contribute scientifically and to teach for at least two more decades. He noted in a second oral history that his last course at Hopkins Marine Station was in 2014.

“Chuck Baxter was probably my best friend, certainly the most influential one,” said James Watanabe, a retired lecturer at Hopkins. “I’ve known Chuck for 50 years, since I was a naive know-it-all Stanford undergrad. He was my teacher, my mentor, my most valued colleague, a sounding board for crazy ideas that would pop into my head, and most of all a steadfast dear friend. There was no topic in biology or farther afield that he couldn’t discuss cogently with deep insight. It seems like everything I may have accomplished as a biologist or a teacher traces back to Chuck.”

Other adventures

From 1978 to roughly 1982, Baxter took a leave from his teaching to join the planning group for the Monterey Bay Aquarium. He later contributed to the production of the PBS series The Shape of Life and consulted on another, National Geographic’s Strange Days on Planet Earth.

In 2000, the Western Society of Naturalists named Baxter as its “Naturalist of the Year,” declaring him an “unsung hero who defines our future by inspiring young people with the wonders and sheer joy of natural history.”

In 2004, Baxter participated in a famed Hopkins-led expedition to the Sea of Cortez which retraced the 1940 journey by Doc Ricketts and author/friend John Steinbeck aboard the sardine-boat-turned-research-vessel Western Flyer to study the ecology of Mexico’s Baja Peninsula. The cruise captured the popular imagination. National Public Radio sent a reporter to tag along. Donations and encouragement poured in. One proposition came from a frustrated marine biologist who’d bought a brewery instead. He offered to supply a staple of Ricketts’s and Steinbeck’s journey – beer.

From the Sea of Cortez expedition (left to right): Rafe Sagarin, Chuck Baxter, and Bill Gilly. (Image credit: L.A. Cicero)

“He sent down five cases for us to sample, which we did and found it very acceptable,” Baxter recalled with a laugh. “So he shipped down 70 cases … to load for the trip down to Baja.”

“Chuck was immensely knowledgeable, creative, curious, generous, and caring, always interested and interesting,” wrote biology Professor Fiorenza Micheli, the David and Lucile Packard Professor of Marine Science and co-director of the Stanford Center for Ocean Solutions and Hopkins Marine Station, in an email announcing Baxter’s death. “He had an extraordinary impact and positive influence on generations of students and colleagues, and he will be deeply missed.”

Baxter is survived by his wife, Susan Harris, of Carmel, California; sons Greg and Jeff, and daughter Cheryl, and five grandchildren.