Get to know the Papua New Guinea Sculpture Garden

The Papua New Guinea Sculpture Garden on the corner of Santa Teresa Street and Lomita Drive has been a feature in Stanford’s landscape since 1994 when 10 artists from the Sepik River region of Papua New Guinea spent four months in the oak grove chopping and chiseling wood and stone into depictions of their myths and legends. During their residency, there were musical performances at the sculpture site, a weekly lecture series on Papua New Guinea, and bark painting classes. The artists talked to the public through a translator about their craft and culture and engaged with local K-8 student visitors. They also enjoyed campus barbeques and evening music sessions with Stanford students.

Go to the web site to view the video.

The 10 artists selected to come to Stanford were recognized as the most accomplished master carvers in the Sepik River region. They came from six villages in the Iatmul and Kwoma societies, and for most, it was their first opportunity to work outside Papua New Guinea. Ranging in age from 27 to 74, they typically worked in trans-generational teams, combining the extensive mythic and artistic knowledge of the older men with the physical strength of the younger men.

Integral with the actual carving, the artists collaborated with Papua New Guinean landscape architect Kora Korawali, American architect Wallace Ruff, and Stanford stakeholders to develop the site plan for the garden. The goal was to reinterpret Papua New Guinean artistic and design perspectives from the two cultural groups within the new context of a Western public art environment.

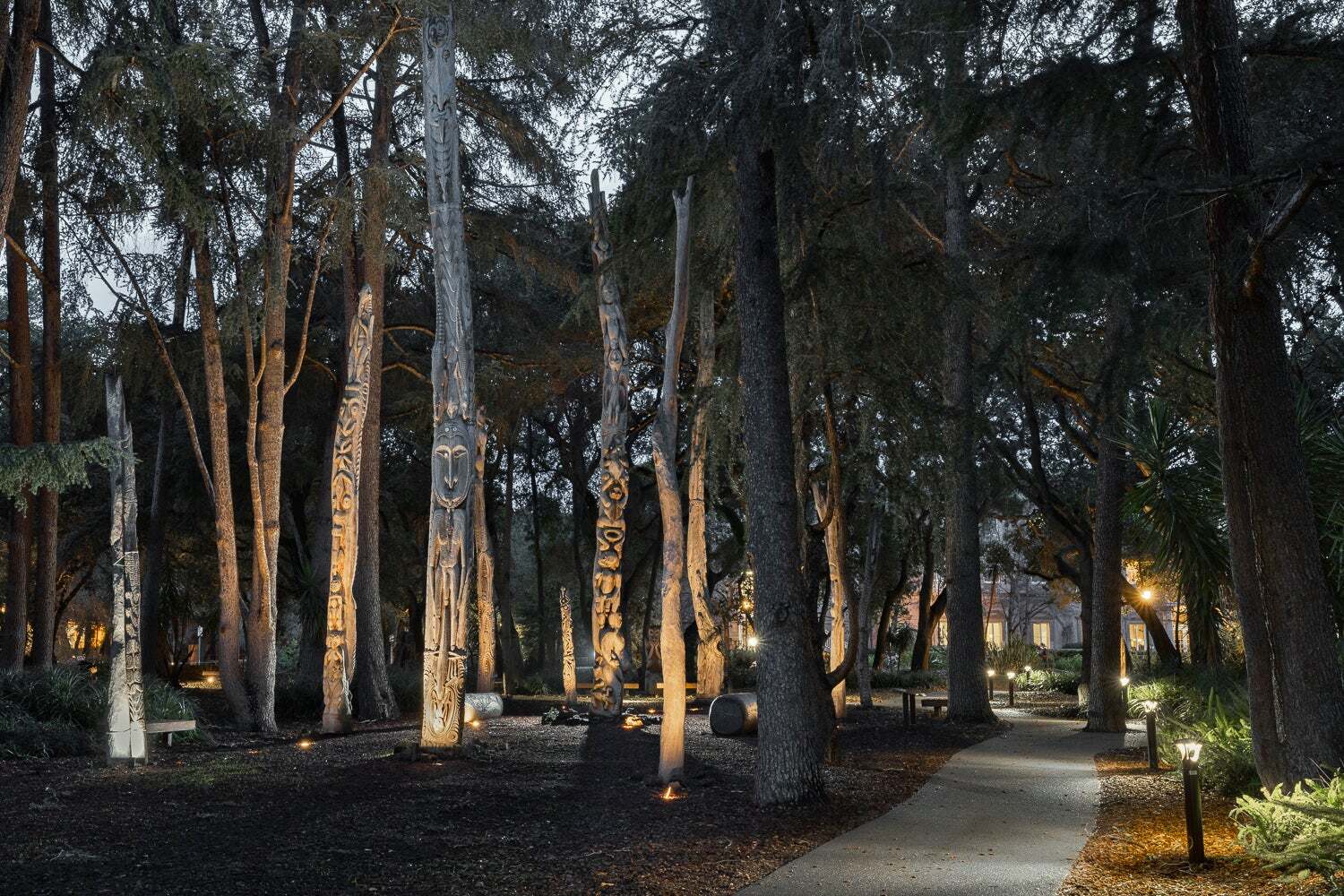

After the artists completed their residency, their sculptures were secured in place, and the site plan was further developed for visitors with pathways, landscaping, lighting, and labels. The artists returned to campus in 1996 to conduct an official sunrise-to-sunset drum and dance ceremony. This Papua New Guinea tradition capped a five-day celebration of the garden’s official opening. Since then, the garden has been accessible to the public 365 days a year, with Cantor Arts Center docents offering monthly tours.

The idea for the garden came from two Papua New Guinea artists, Naui Saunambui and Yati Latai, who proposed creating an art project in the United States to Jim Mason, ’91, MA ’94, during his anthropological fieldwork on the Sepik River in 1989. Interested in continuing to engage with the people who generously supported his research, Mason returned to Stanford and began organizing and fundraising for a sculpture garden under the sponsorship of the Department of Anthropology in the School of the Humanities and Sciences. Four years later, he returned to Papua New Guinea to assemble a group of artists, including Saunambui and Latai, and escort them to the Stanford campus, where he oversaw the project to its completion.

The artists produced 40 carved posts, freestanding individual figures, garamut slit drums, and other large-scale site-specific works that are part of Cantor’s outdoor art collection. The project was an opportunity to create a dialog between the artists and the Stanford community, where students could learn about the concerns and life experiences that motivated the artists’ work, and the artists could learn about campus life and the broader Bay Area.

Watercolor illustration of a spirit house by Alison Amberg, MA ’16, included in the book titled To the Beat of the Garamut Drum written by Stanford Graduate School of Education classmate Christie SmithYoung, MA ’16, as their Sanford Teacher Education Program elementary final social studies project in 2016.

The figures painted on Kwoma posts are mostly abstractions of totemic plants and animals belonging to the clan of the artist. The underside of the roofs in Kwoma spirit houses would be covered with similar paintings on bark panels.

Materials

Two significant elements of the sculpture garden are the grouping of tall posts on either side of the central path that suggests spirit houses. In Sepik River villages, elaborately decorated spirit houses function as ceremonial spaces and social centers for conversation with good friends, rest after a day of hard work, and enjoyment of their world’s visual and mythic accomplishments. This communal and contemplative atmosphere has been recreated in the garden by the carved and painted posts arranged in two typical spirit house floorplans. Usually, these structural members would support walls and a roof, but at Stanford, they remain exposed for optimal viewing.

Figures on both sets of posts and the large garamut slit gong drums depict various stories of creation, histories of clan ancestors, and nature spirits that populate the religious lore of the Kwoma and Iatmul people. The drums are played during celebrations and ritual occasions in the spirit house, as well as to call spirits and communicate between villages in an elaborate percussive language.

Posts in Kwoma spirit houses are traditionally painted using earth-based pigments. At Stanford, the artists used acrylic latex color-matched to the Indigenous paints. Iatmul spirit house posts typically combine carved and smooth posts. The most common carving woods for spirit house posts and freestanding sculptures in Papua New Guinea are indigenous kwila (Instia bijuga) and garamut (Vitex confassus), which the artists sourced in Papua New Guinea and shipped to Stanford for the project.

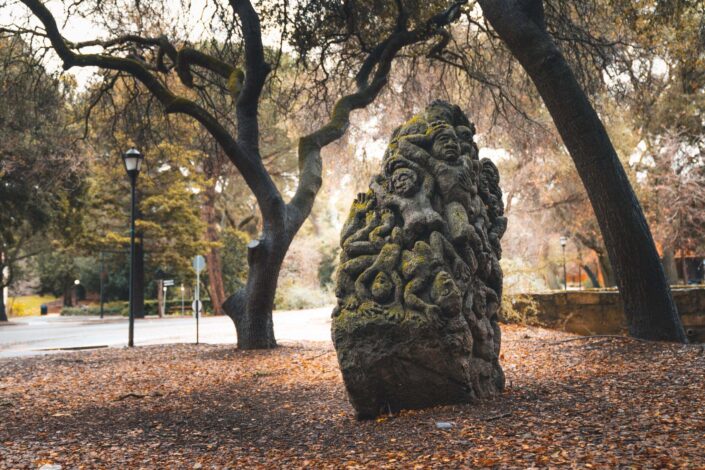

Experimenting with new materials and forms is a tradition for visiting artists at Stanford. Stone is not a traditional carving medium on the Sepik River, so pumice stone was obtained near Mono Lake on the California-Nevada border to allow the artists to expand their craft with cement adzes and chisels.

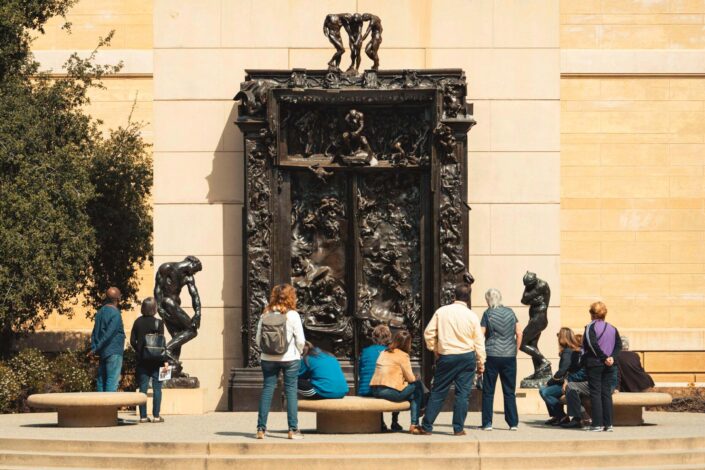

Reinterpreting Rodin

Papua New Guinea artists Simon Gambulo Marmos and Jo Mare Wakundi reinterpreted two bronze works by August Rodin in the Cantor’s collection to relate to Iatmul myths: The Thinker and The Gates of Hell.

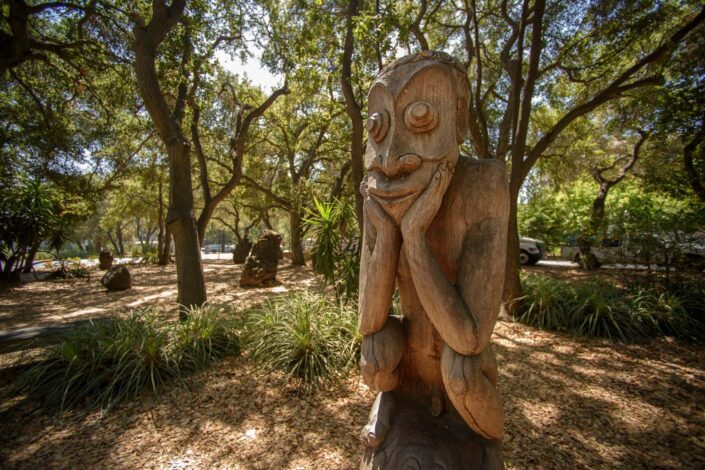

Carved in wood, The Thinker (Yerakdu) in the Papua New Guinea Sculpture Garden depicts the story of an ancestor sitting alongside the hole from which he emerged into the world. He is thinking about how he can create fellow humans out of clay. His first attempt has just failed, and broken body parts are scattered around his feet.

The Gates of Hell / Opawe and Namawe, carved in pumice stone, references the story of a flood that destroyed the ancestral world after a man tricks his older brother into killing his wife. The younger brother’s family is depicted on one side of the stone sculpture, and the twisted bodies of the village people drowning in the flood are on the other.