The movers and shakers of Stanford’s earthquake center

From a single footfall to catastrophic tremors, waves of impact are all around us. The researchers at the John A. Blume Earthquake Engineering Center study the world’s vibrations – big and small.

Go to the web site to view the video.

Inside Stanford’s John A. Blume Earthquake Engineering Center, a remote-controlled toy car carrying a very special payload zips over the 8-foot span of a model bridge. The unique cargo – a vibrational sensor – reveals the bridge is cracked. Fortunately, this is only a test and researchers created the fissure on purpose to verify the sensor worked. Like most experiments at the Blume Center, however, this work aims to someday make its way off campus and into the real world.

Lying near a famous seismic hotspot – the San Andreas fault system – it’s no surprise that Stanford’s John A. Blume Earthquake Engineering Center houses investigations of earthquakes from every angle. But these researchers also use their expertise to study human health, climate change, urban planning, alternative building materials, and Martian soil – all in the pursuit of better, more beneficial, engineering.

“We don’t engineer earthquakes here,” joked Gregory Deierlein, who is the John A. Blume Professor in the School of Engineering. “Rather, we’re interested in engineering better buildings, better communities. We do a combination of experimental testing, computational modeling, developing theories, and applying them. We also engage with practicing engineers, community leaders, and so forth to understand what cities can do to safeguard their communities.”

Activities within the Blume Center include research, instruction, publication of reports and articles, and sponsorship of seminars and conferences. The center is part of the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, which is in the School of Engineering and the Stanford Doerr School of Sustainability, but also enables cross-department collaborations. Research that happens within the Blume Center spans a wide range of topics but the common themes are safety and the future.

“The best part of earthquake engineering – and civil engineering in general – is it’s an altruistic endeavor,” said Deierlein. “In other words, we’re here to make buildings safer and make communities more resilient. At the end of the day, everything we do has that in mind.”

Testing, testing

The varied vibrations that permeate our lives cannot be captured through just one method. For this reason, researchers associated with the Blume Center rely on physical and computer-based simulations, as well as real-world tests outside the lab. The physical testing equipment inside the center includes shake tables and several reaction frames, which replicate various activities – from footsteps to extreme ground shaking – that structural systems and materials of buildings might encounter.

Deierlein uses physical experiments combined with computational simulations to painstakingly characterize how severe the shaking of a particular earthquake would be, and how that would affect structures made of different materials – masonry, concrete, structural steel – or of different types, like low-rise buildings or skyscrapers. Michael Lepech, professor of civil and environmental engineering, conducts physical tests on new composite materials his lab is developing with a focus on sustainability. These tests often aim to replicate the amount of wear and tear a structure might experience over its lifetime from basic daily use – such as traffic on a bridge or wind on a building. In many cases, the physical data produced in the Blume Center are the basis of further computational modeling.

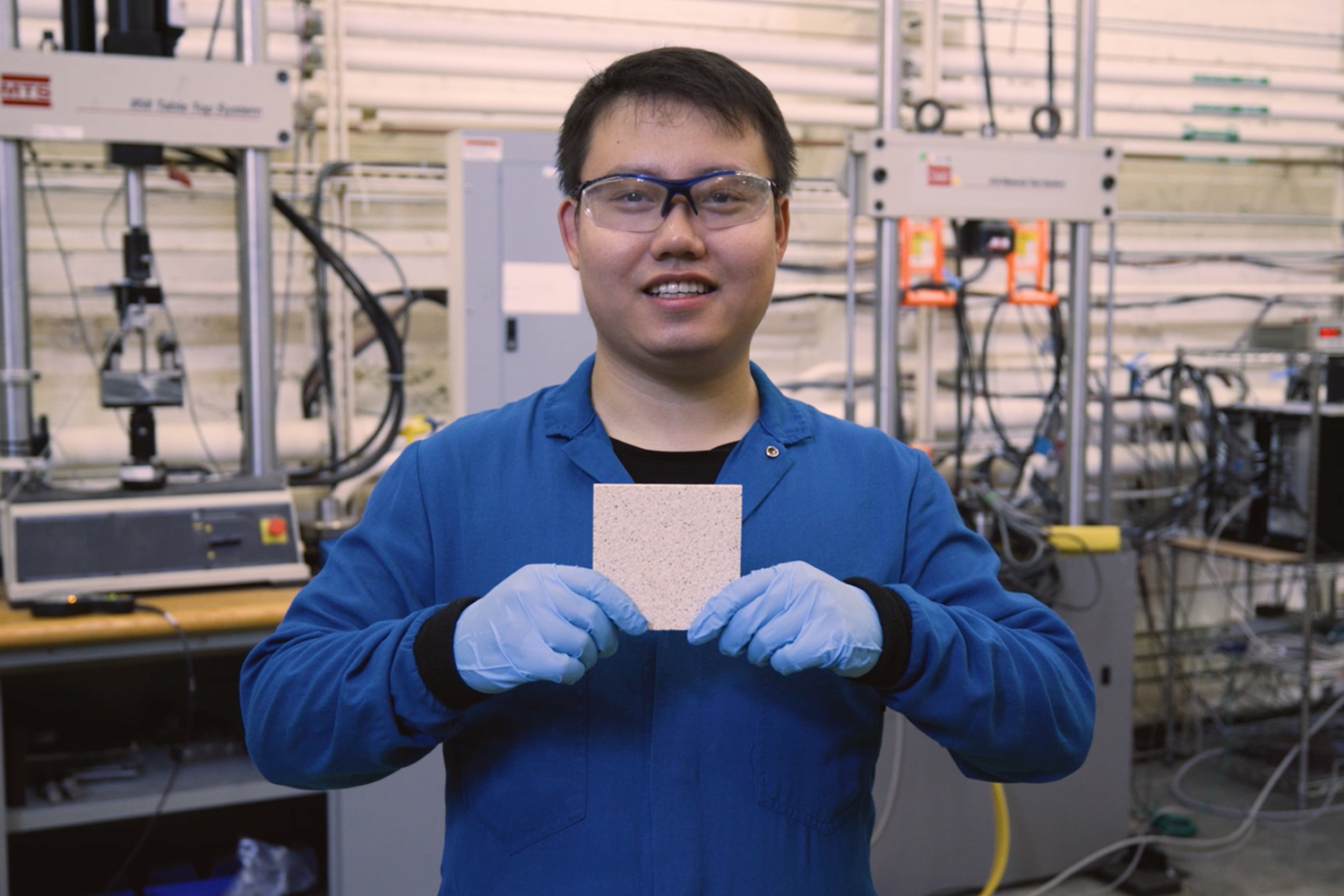

Structural Engineering and Mechanics master’s student Yinjian (Klay) Li holding a fiber reinforced polymer test specimen that is getting prepped for tensile fatigue testing, as part of research led by Professor Michael Lepech. The speckles on the surface of the specimen help researchers digitally measure strain during the testing. (Image credit: Harry Gregory)

“At the Blume Center, we’ll test materials with small amounts of load for a few hundred thousand cycles,” said Lepech. “But we want to know millions, tens of millions, of cycles. So we train our computational models on the test cycles and then extend those out.”

The experimental testing equipment at the center captures measurements of stress and strain through advanced cameras, sensors, and software. Once the data is in a computer model, Lepech can also detail the effects of humidity and ultraviolet radiation on the materials to create a more complete picture of how new construction materials should fare over time.

Physical tests orchestrated by Hae Young Noh, associate professor of civil and environmental engineering, are diverse – including setups, like the toy car, which are reminiscent of old practical movie effects.

“We are collecting vibration data from real world bridges in San Jose and Palo Alto. We are also testing our methods on a small-scale prototype in the Blume Center,” said Noh.

Safety first

Noh is also hoping the sensors can help places like medical facilities improve inferences about individual health and well-being. Subtleties in vibrations can imply activity – like washing hands or grabbing supplies – but they might also hint at changes in physical or even cognitive health. To test this, her lab has already collaborated with hospitals and elder care centers.

“The ultimate goal of this research will be to understand who’s in the building, what they’re doing, and what is needed for them to be healthy and productive inside the structure,” said Noh. “If we can capture behaviors that are out of routine for people, we can save lives.”

Noh has also set up vibration sensors at Maples Pavilion to understand crowd activity. Such data could influence facilities and concessions management, interactive crowd activities, and safety measures.

Associate Professor Hae Young Noh (center), with graduate students Sulagna Sarkar (left) and Yiwen Dong (right), assembling sensors before installing them at Maples Pavilion. (Image credit: Harry Gregory)

Addressing health from another angle, Lepech is concerned with the environmental influence of buildings on the world around us, including CO2 production, acidification, and potential carcinogens, and how small changes to materials can have significant effects far in the future. This expertise has led to collaboration with NASA Ames, which aspires to produce lightweight, waste-free, 3D-printable structural materials that can be manufactured on-the-spot in space. Those goals, though, are just as applicable on Earth.

“That set of projects provides a crucible by which we have to create materials and perform construction that is highly circular in nature, uses only renewable energy to power it, and is done by almost entirely automated means,” said Lepech.

Sustainability at every scale

Due in part to the establishment of the Stanford Doerr School of Sustainability, researchers who do work in the Blume Center are also increasingly applying their traditionally earthquake-focused methods to scenarios related to climate change, sustainability, and the future of regions most likely to be affected by natural hazards.

For example, Barbara Simpson, an assistant professor of civil and environmental engineering, who studies structural performance and aims to reduce the effects of natural hazards on the built environment, is currently running tests in the Blume Center on models of offshore wind turbines. Like Lepech, Sarah Billington, the UPS Foundation Professor and chair of the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, has conducted research on a variety of alternative, sustainable construction materials. She now studies how buildings can improve human well-being through innovative connections to nature in built environments, as well as methods of increasing building material supply chain transparency to eliminate forced labor. The research group led by Jack Baker, professor of civil and environmental engineering, also has various projects looking at the effects of storm surge, sea-level rise, and wildfires.

Graduate students Doyun Hwang and Sulagna Sarkar assembling a sensor box for vibrational studies at Maples Pavilion. (Image credit: Harry Gregory)

Research at the Blume Center begins at the most foundational levels, pushing the limits of our knowledge about how buildings behave. Its scope has also expanded to include the bigger context in which a building operates – for example, how important infrastructure for health care, services, and schools recovers from an earthquake or other natural disaster. This broad scope requires thinking far ahead to consider how policies related to building codes, retrofit, and other mitigation could play out, years and decades into the future.

“I’m very energized by working with practicing engineers and communities to look at the practical impact of our work,” said Deierlein. “We’re always bringing it back to this very altruistic mission. That, to me, is what we can herald in civil and earthquake engineering.”