Writing haiku bridges intergenerational gaps and inspires appreciation of nature

A popular fall class on the short Japanese poetic form haiku explores the role of creative verbal arts in fostering cross-generational connections.

Yoshiko Matsumoto (left), the Yamato Ichihashi Chair of Japanese History and Civilization and professor, by courtesy, of linguistics, teaches Sharing Conversations Across Generations: The Magic of Haiku. (Image credit: Andrew Brodhead)

For Molly Miller, ’26, creating haikus with older people at a local adult day services center brought a welcome change of pace during her busy fall quarter.

“It was really great to get off campus and interact with older people,” Miller said. “I don’t have a lot of intergenerational relationships in my life and so it was nice to actually have these interactions, write these haikus, and kind of reflect on the class material in the context of my firsthand experience.”

In the fall quarter course, Sharing Conversations Across Generations: The Magic of Haiku, students explored the role of creative verbal arts – in particular, the short Japanese poetic form, haiku – in fostering cross-generational understanding and connection.

Miller, an engineering major, was drawn to the course’s service component – it’s a Cardinal Course certified by the Haas Center for Public Service – but says she herself benefited from the experience.

“It helped me relax to do something different,” Miller said. “There should be more classes like this. I feel like a lot of times, it’s overly structured and academic, and this is a nice way to connect with people and ourselves.”

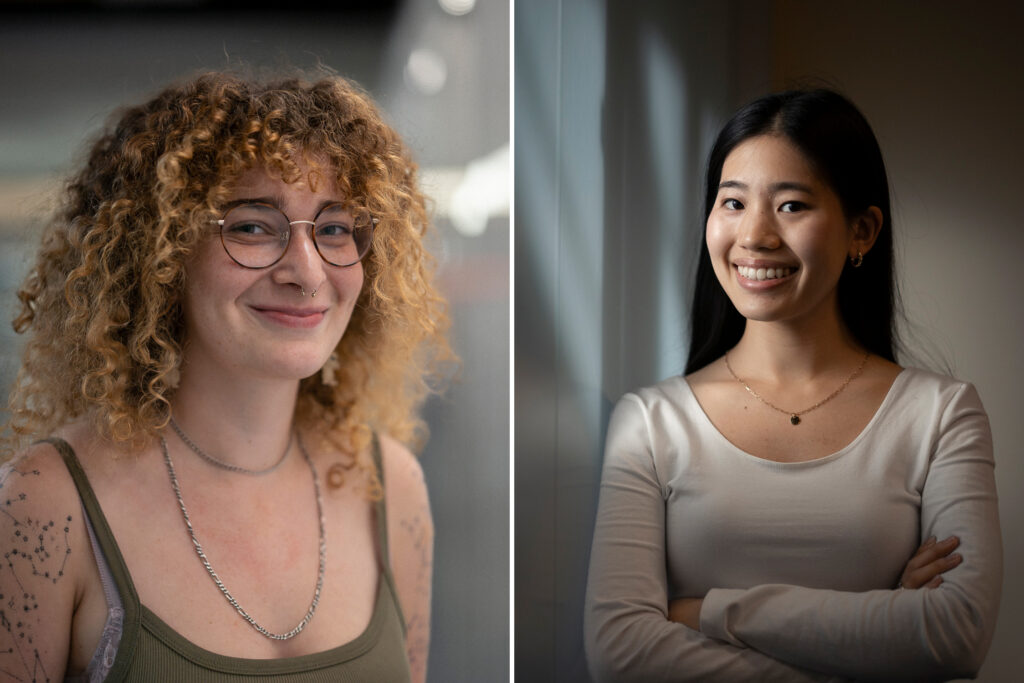

Molly Miller and Sana Sugita are students in the course Sharing Conversations Across Generations: The Magic of Haiku, which has drawn undergraduate and graduate students from across disciplines. (Image credit: Andrew Brodhead)

‘A pleasant surprise’

The class came to fruition following a creative pivot by Yoshiko Matsumoto, the Yamato Ichihashi Professor of Japanese History and Civilization in the Department of East Asian Languages and Cultures and professor, by courtesy, of linguistics in the School of Humanities and Sciences, who teaches the class with graduate student Harumi Maeda.

In March 2020, Matsumoto was awarded a Cultivating Humanities grant (now called a Humanities Seed Grant) through the Changing Human Experience (CHE) initiative, which advances research in the humanities, arts, and social sciences that illuminates key issues of our time.

As one of eight funded projects, Matsumoto proposed to explore how communities can be inclusive of older adults with diverse conditions, including dementia. The pandemic interrupted her plans for a research trip to Japan, where the large population of older adults has inspired a number of trials and projects for integrating people with dementia into the community through daily activities.

So she considered an alternate challenge: how to foster intergenerational communication while in isolation. A surprising catalyst emerged: the Japanese art of haiku.

Students have found that studying haiku helps them notice the natural beauty around them more often, Professor Yoshiko Matsumoto said. (Image credit: Andrew Brodhead)

The power of five-seven-five

A haiku is a three-line poem – traditionally about nature – with five syllables in the first line, seven in the second, and five in the third.

The form’s simplicity puts younger and older poets on fairly equal footing, Matsumoto said, and makes it an easy entry to conversation and collaboration. She conducted a pilot study in which students met with local older people over Zoom to create haikus together, and then analyzed the recorded sessions. Seeing a positive response, she developed the course inspired by her findings.

Students and older adults who may have declining cognitive function bring different strengths to writing haiku, Matsumoto said.

“Haiku is like a snapshot of scenery or emotion, like drawing impressions,” Matsumoto explained. “So even if someone can’t really create a very logical sentence, that is actually a benefit rather than a detriment.”

And students “may be able to think very clearly with great verbal ability and vocabulary but in terms of poetic feelings, they don’t have deep life experience and they may feel uncomfortable doing this with people who are older.”

Creating haikus together often leads to discussing other topics and interests, Matsumoto said. “They can create a personal connection from that conversation, and they can be curious about each other, rather than being told to talk about themselves.”

The course is open to undergraduate, graduate, and medical school students, and has drawn interest across a wide range of disciplines, including aeronautics, economics, human biology, Asian American studies as well as literature and linguistics.

Matsumoto said it’s been rewarding to hear students talk about how learning haiku has impacted them.

“Before, they didn’t stop while walking on campus, and now they notice nature and they can express themselves through haiku,” she said. “It has really opened up different aspects of their lives.”

Bridging the gap

In the course, students discussed issues related to aging, inclusivity, power relationships, citizenship, and effects the arts can have on connection.

Students visited the Peninsula Volunteers Inc.’s (PVI) Adult Day Services Rosener House in Menlo Park where they met in small groups with older adults to create haikus over three days. They also visited Jasper Ridge where they used the setting as inspiration to create their own haikus, which are now displayed at the East Asia Library.

Shanah Hawk, the program manager of adult day services at PVI’s Rosener House, said the haiku workshop was a welcome addition to their programming.

About 75% of clients at the Rosener House have some sort of cognitive impairment, and many were initially hesitant about trying the haiku activity, Hawk said. “Once they saw that they could do it, they had a sense of pride that they can try new experiences,” she said. “It really had a positive impact on how they perceive themselves.”

The haiku activity incorporated images of nature as inspiration, which made the activity accessible as well as sparked memories and further conversation, Hawk said.

“Even with a dementia diagnosis, they are still active members of society and our community,” Hawk said. “Seniors, in general, are kind of the invisible generation and then you add on a chronic condition and they get pushed even further away. I love that so many students are taking the initiative to bridge the gap that we have right now.”

Sana Sugita moved to the U.S. from Japan this past September and is a first-year master’s student in East Asian Studies. “What I liked about this class is that we get to go outside of Stanford to engage with a generation of people I would never be able to meet otherwise. As a Japanese person, it also let me see the significance of haiku and how it could serve as a soft power.”

At the Rosener House, Sugita worked on a haiku with a man who shared with her about his time living in Lake Tahoe. In turn, Sugita told him about living in Japan. “I think we really elevated each other in a way to create a better haiku and also to learn from each other,” she said. “I saw a lot of value in that.”

“I think it was my favorite class this quarter,” she added. “It was just very different and really an eye-opening experience.”