A Stanford program trains teens in research methods using their school as the subject

Bay Area high school students took the lead on a study of district programs and policies that affect student well-being, with help from veteran researchers at Stanford.

When the Sequoia Union High School District (SUHSD) set out this year to find new ways to support students’ mental health, an unusual research opportunity emerged.

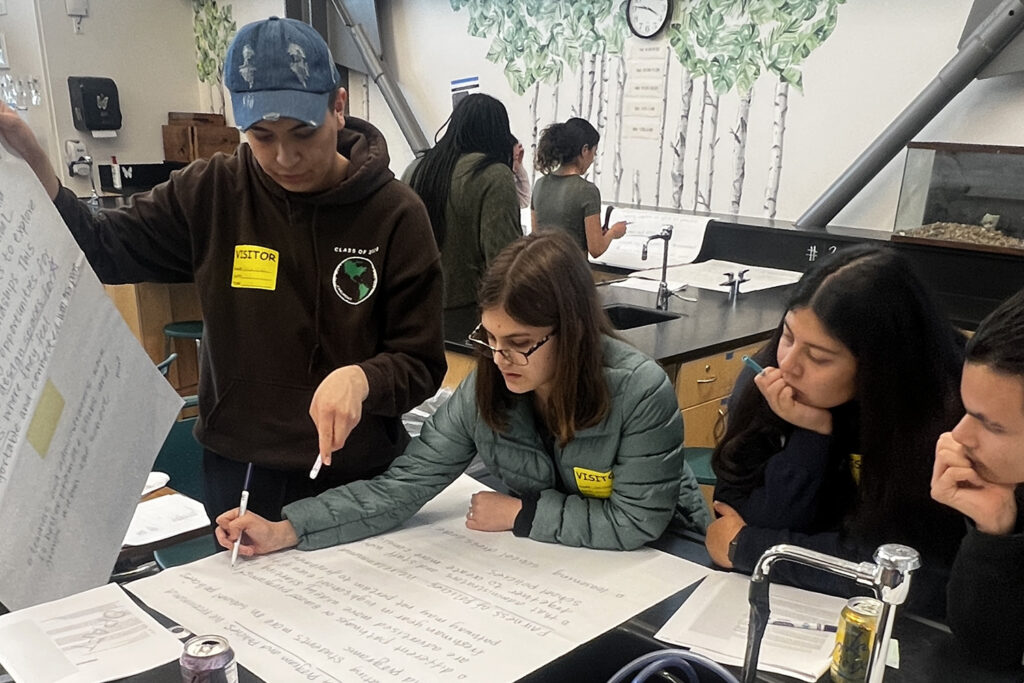

A team of investigators met with students from across the district, conducting in-depth interviews about their school experience. They synthesized the wide-ranging responses they collected into a detailed report, then presented their recommendations to district and community leaders.

Here’s what made the project so extraordinary: The investigators were high school juniors and seniors from the district itself.

None of the students had conducted a project like this before. But with guidance from researchers at Stanford, the high schoolers learned how to craft research questions, conduct interviews that elicit meaningful information, and develop a set of findings the district could use to inform changes in its programs and policies.

The experience, led and funded by Stanford, was one of several “youth action research” efforts implemented in recent years by the Stanford Graduate School of Education’s John W. Gardner Center for Youth and Their Communities.

By engaging young people as collaborators in research about their lives, the approach provides rich and reliable insight for policymakers, and it empowers students with a meaningful role in bringing about change in their community.

“We’re offering a model where students are partners – full collaborators and thought partners,” said Kristin Geiser, deputy director and senior research associate at the Gardner Center. “You tend to get better information this way, because you have peers asking the questions. You’re also building the students’ skills and confidence, and showing them how they can make a difference. It’s a win all around.”

Beyond surveys and focus groups

When SUHSD administrators reached out to the Gardner Center, they had plenty of data from surveys and participation in support programs. But that only provides a snapshot of students’ experiences, said SUHSD’s Multi-Tiered System of Support coordinator Shana Karashima.

“You tend to get better information this way, because you have peers asking the questions. You’re also building the students’ skills and confidence, and showing them how they can make a difference.”

—Kristin Geiser

Deputy Director and Senior Research Associate at the Gardner Center

“What we were missing was their voices and perspectives,” she said. “Are we actually matching what students want and need? We wanted a fuller, more colorful picture.”

Stanford has a long history of partnering with SUHSD and the Redwood City School District, including the 2020 launch of the Stanford Redwood City Sequoia School Mental Health Collaborative. For this particular research project, SUHSD sought to better understand factors that affected students’ sense of belonging and the ability to manage their emotions.

The Gardner Center proposed the youth action research model as a way to not only elevate students’ voices but also support their overall growth.

“Youth voice has gotten a lot of lip service in education research,” said Laurel Sipes, a senior research associate at the Gardner Center. “But there aren’t many meaningful attempts to empower students to have a significant voice in their school districts’ decision-making processes. We wanted to do something that would not only yield useful findings, but also give students the chance to learn new skills and collaborate in a meaningful way.”

Having young people conduct the study also taps into nuances that are specific to the generation’s experience, said Liz Newman, a senior community engagement associate at the Gardner Center.

“If we, as adults, were asking the questions,” she said, “we would probably ask them in a different way, and the students [being interviewed] would almost certainly answer us differently. The student interviewers also make sense of the answers in a different way from how we would, because they’re looking at it through the lens of their own experience, which is really valuable.”

Students also come to the project without the competing agendas that administrators often face, said Karashima. “They’re not influenced by district politics,” she said. “They don’t have an agenda, beyond wanting their schools to feel like a place where they want to be and learn and to be prepared for life after high school. They’re getting the purest, most honest information about what’s really happening.”

Establishing a team

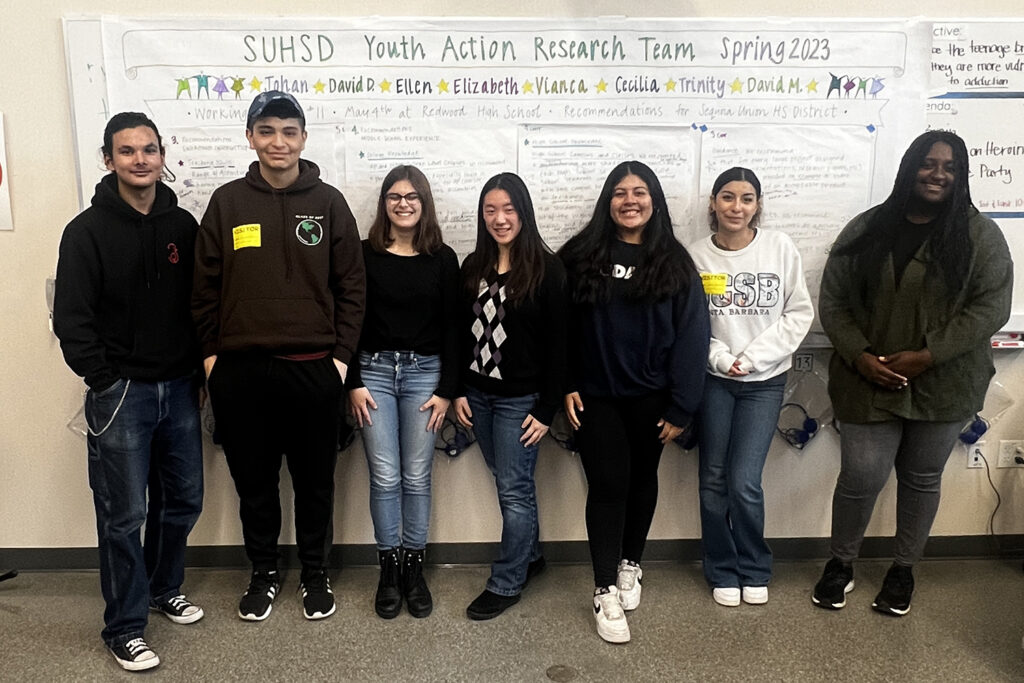

Newman and Sipes selected eight students from a pool of more than 60 applicants. One member, David Diaz, was a senior at Carlmont High School, drawn to the prospect of advancing a system of support services that had helped him and his peers in the past. “I had also recently taken a college psychology class and started learning about different research methods, which really sparked my interest.”

“Youth voice has gotten a lot of lip service in education research. But there aren’t many meaningful attempts to empower students to have a significant voice in their school districts’ decision-making processes.”

—Laurel Sipes

Senior Research Associate at the Gardner Center

Elizabeth Kao, then a senior at Carlmont High School, had been serving on a youth advisory committee for the city of Belmont, implementing activities that address issues affecting youth in the community. When she learned about this research project, she saw an opportunity to better understand the factors underlying some of those issues. “With this research, we were finding the evidence behind why things are a certain way, and then we were able to make recommendations based on the evidence.”

The team met weekly with Newman and Sipes for instruction and coaching on every stage of the process. They also built on the district’s original research questions, adding lines of inquiry about how classroom instruction could be more engaging and what might have better prepared them for high school.

The interviews were not recorded, and the students were trained on the importance of maintaining confidentiality. They were also coached on ways to respond if their questions elicited emotional responses.

“It’s a skill not just to get the information, but to honor the person you’re interviewing,” said Geiser. “That’s all part of doing research.”

Transforming feedback into findings

Students shared an array of school experiences that affected their well-being. They described ways that teachers, peers, and programs made them feel seen and included, and policies they found detrimental. They identified challenges to managing their emotions at school, such as barriers to using mental health services and even having grades released during school hours.

They talked about classroom activities that motivated them, and others that made it harder to connect with the material. They shared experiences they wished they’d had in middle school, like more information about AP courses and “shadow days” to meet current high schoolers and get familiar with the campus.

It all amounted to a lot of feedback and stories – data the youth researchers learned to code into themes and develop into a set of findings.

“It was a little mind-boggling,” said Cecilia Lopez-Sandoval, a member of the research team who was then a senior at Woodside High School. “Personally I love organizing things, but it was so much data, so many points – I didn’t know how we were going to do this. But Liz and Laurel explained the process so well and guided us through it.”

Together the team produced a report that included simple, no-cost recommendations. For example: To support students who want to access mental health services during class time but feel uncomfortable asking permission from their teacher, they offered procedural workarounds to ease that pressure while still accounting for the student’s whereabouts. Another recommendation proposed that teachers have an “open door policy” during the lunch period one or two days a week so that students can come in to talk or just have a safe place to eat.

“The whole experience gave me a new appreciation for how people can change systems,” said Trinity Tyson, a graduate of Redwood High School, who was also inspired by the project to sign up for training with Mental Health First Aid, an organization that helps individuals learn how to identify and respond to signs of mental illness in others.

Diaz went on to do a summer internship at Redwood City Together, where he’s working on a project to investigate the impact of drug and alcohol abuse on youth in the community. “I’ve been able to use a lot of the information and skills that I gained from the Stanford internship, especially with a survey we’re developing right now.”

Karashima said the findings provide strong support for resources her team will advocate for in the coming year. “We can talk about best practices, participation data, federal guidelines, all of that,” she said. “But our own students saying, ‘Here is our experience, and we need this in our classroom or our school’ – that’s much more powerful when we’re making a case to our board.”

The SUHSD Youth Action Research project was funded by the Office of Community Engagement at Stanford, which covered the costs of the Gardner Center researchers’ time as well as stipends for the high school students on the research team.