Newly installed bronze sculptures are an elegy to five extinct North American birds

Artist Todd McGrain’s bird memorial documenting a changing world can now be seen on the Stanford campus. A companion documentary film screening and musical performance are scheduled for Family Weekend.

Carolina parakeets, great auks, heath hens, Labrador ducks, and passenger pigeons once thrived in abundance in the North American landscape from the Labrador and New York shores to the Midwestern plains. The five species are now extinct, but sculptor Todd McGrain’s large-scale bronze sculptures of the birds, an ode to vanished species, can be seen on the Stanford campus.

The temporary installation of the sculptures is courtesy of McGrain and a collaboration of Stanford Live, the Anderson Collection, and the Office of the Vice President for the Arts as part of a range of programming exploring art and sustainability. The birds connect the visual and performing arts on either side of Palm Drive in the arts district. “Hosting two of Todd’s striking bronze birds at our entrance not only activates our corner of the arts district with outdoor art, but they also bring attention to an important development in North American natural history,” said Jason Linetzky, director of the Anderson Collection. “The work is inspiring and brings renewed focus to the natural environment that surrounds us.”

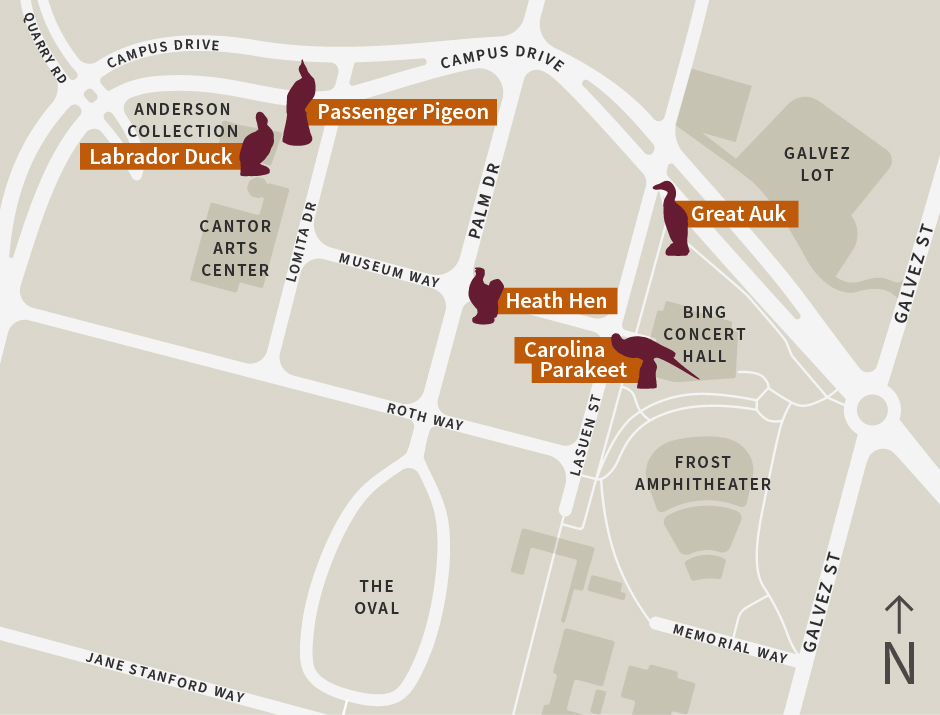

Other collaborations include a self-guided tour of The Lost Birds in Stanford’s mobile app, which now features a guide to campus public art in its “Discover” section. Seeing all five sculptures on foot takes approximately 20 minutes over a half-mile loop.

Complementing the birds’ year-long residency on campus is a free screening of the documentary The Lost Bird Project on Friday night, Feb. 24, in Oshman Hall in the McMurtry Building. A Q&A with McGrain and the film score composer Christopher Tin, ’98 and MA ’99, follows the screening. On Saturday, Feb. 25, the musical composition The Lost Birds by Tin will be performed live by VOCES8 in Bing Concert Hall.

McGrain’s project, which includes the creation of five original sculptures and their installations in the locations where the birds met their demise, as well as the second edition castings at Stanford, combines art, natural history, and a long road trip to create a public memorial to birds driven to extinction.

The artist’s goals for the project were to create a moving record of dwindling biodiversity, chronicle humankind’s impact on our changing world, and bring these five birds back into the world in some fashion.

After creating the sculptures, McGrain traveled to the locations where the birds were last seen in the wild and negotiated for permission to temporarily install the sculptures. “Working closely with local communities has been a true pleasure,” said McGrain. “It was also essential to ensure that the memorials were warmly welcomed into the fabric of the communities to which they ultimately belong.”

The Heath Hen installation on Martha’s Vineyard was the most challenging and ultimately the most rewarding for McGrain. He recalls, “Once installed, it was like a dream to finally see the monument at home on the site where so many people had committed themselves to saving this iconic species as it lived out its final days.”

McGrain’s adventures are captured in the documentary The Lost Bird Project. The film score by Tin evokes the majesty of the birds and the pathos of their extinction.

“This project provides so many entry points to our season theme of place and healing,” said Laura Evans, director of programming and engagement with Stanford Live. “Anchored around the performance, we collaborated with Todd on bringing the bird installation here and screening the documentary that first brought Chris and Todd together.”

“Since the birds arrived on campus, they have been engaging people like nothing else we have done, demonstrating the power of art to help confront issues like species extinction in a way that inspires hope and reflection over denial and despair.”

Meet the lost birds

1. Carolina Parakeet, located between Bing Concert Hall and Frost Amphitheater

In the past, Carolina parakeets ranged over much of what is now the eastern United States. As the landscape was transformed for agriculture, the birds were attracted to the new food sources. In response, farmers shot them in great numbers. As a communal species, when one bird died, the flock flew to its side, thus ensuring the demise of many more.

Populations were further diminished by feather hunters, trappers who sold them as pets, and competition from European honeybees for roosting sites. The last two known Carolina parakeets lived together in the Cincinnati Zoo for 32 years. Lady Jane died in 1917 and Incas soon after, on Feb. 21, 1918.

2. Great Auk, located on the southeast corner of Campus Dr. and Lasuen St.

Swift and agile in water, great auks lived most of their lives at sea. But each spring, they came with their life-long partners to mate on the isolated rock islands of the North Atlantic. Flightless and awkward on land, they were easy targets.

By the mid-1500s, their numbers had drastically declined as hunters sought their meat, eggs, oil, and especially their feathers. The last documented pair of great auks were killed on Eldey Island, off the southwestern tip of Iceland, on June 3, 1844.

3. Heath Hen, located on the southeast corner of Museum Way and Palm Dr.

Heath hens once ranged from the southern tip of Maine to Virginia. But by 1870, hunting by European settlers had reduced the population to a few hundred birds on Martha’s Vineyard. Efforts to save them were enacted, but wildfire, disease, and the unfortunate arrival of predatory goshawks ravaged the remaining population.

In 1929, a hopeful male named Booming Ben was witnessed calling out to others of his kind, but none were left to hear his plea. He was last seen on March 11, 1932.

4. Labrador Duck, located in front of the Anderson Collection

The Labrador duck once migrated along the East Coast of North America from Labrador to the Chesapeake Bay. Diving through silt and shallows, it used its wide, flat bill to feed on mussels and shellfish.

Not especially popular as a game bird, the reasons for the species’ extinction remain unclear. Habitat loss and diminished populations of shallow-water mollusks, a primary food source, are thought to have played a role. The last known Labrador duck was shot on Dec. 12, 1878, in Elmira, New York, having been blown inland by a huge storm.

5. Passenger Pigeon, located in front of the Anderson Collection

At one time, passenger pigeons accounted for an estimated 20 to 40 percent of all land birds in North America. They flew in vast flocks numbering in the millions, sometimes eclipsing the sun for hours. As America’s human population grew and the demand for wild meat increased, hunters slaughtered the birds with great efficiency.

On March 24, 1900, a boy in Pike County, Ohio, shot the last recorded wild passenger pigeon. Fourteen years later, under the watchful eyes of her keepers, the last passenger pigeon in human care, Martha, died in her cage at the Cincinnati Zoo.