When Rosa Parks came to Stanford

John Rickford, professor emeritus, reflects on Parks’ 1990 visit to campus, her mark on American history, and the memento she left behind at Stanford.

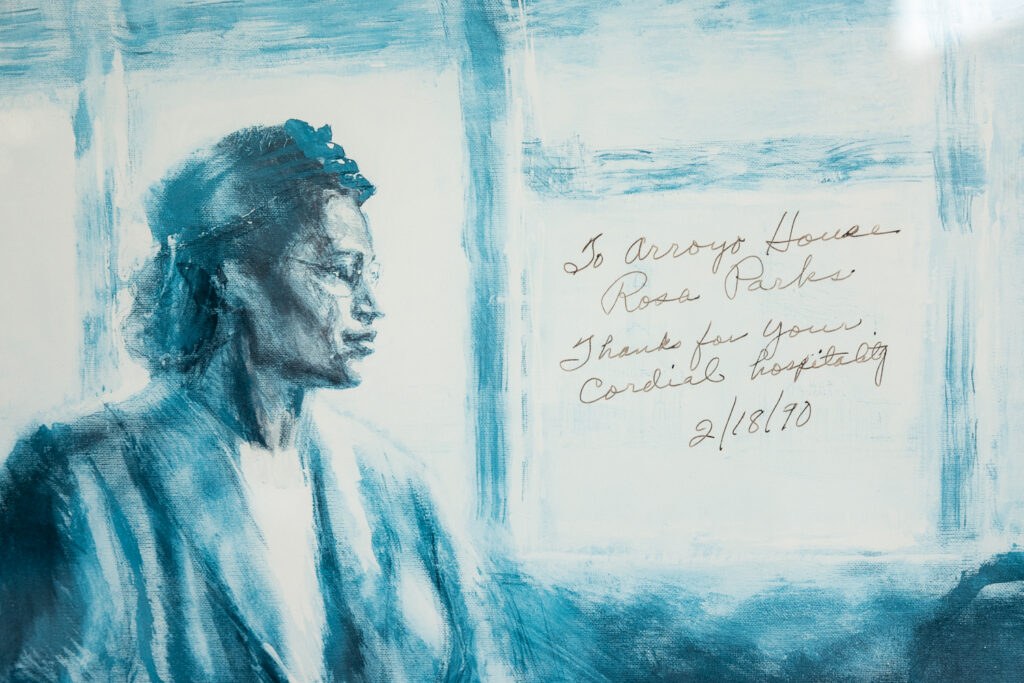

Hanging on a wall in the foyer of Arroyo House is a framed portrait of a woman in a hat and overcoat sitting on a bus. Written on the picture is a message:

A portrait of Rosa Parks, signed by Parks during her 1990 visit to Stanford, hangs on a wall in Arroyo House. (Image credit: Andrew Brodhead)

“To Arroyo House, Rosa Parks. Thanks for your cordial hospitality,” signed on Sunday, Feb. 18, 1990, by Parks, who was then 77 years old.

Thirty-three years later, the portrait remains an inconspicuous memento and a subtle reminder of the iconic activist’s visit to Stanford. Professor Emeritus John Rickford remembers it well.

“She had a very lucid memory and was sprightly and energetic,” Rickford said.

Rickford, who taught linguistics in the School of Humanities and Sciences, and his wife Angela, Stanford PhD ’96, who was a professor of literacy education at San Jose State University, were resident fellows at Arroyo House from 1988 to 1990. In the fall of 1989, one of their resident assistants, Matt McLeod, approached them with the idea of inviting Parks to Stanford.

Parks’ famous 1955 arrest on a bus in segregated Montgomery, Alabama, sparked a year-long bus boycott that catapulted Martin Luther King Jr. to national prominence and made her one of the most celebrated figures of the civil rights movement. Rickford was skeptical that she would accept their invitation.

“I thought, ‘Yeah right. That’s like bringing the president of the United States or something,’ ” he recalled.

But it turned out that Parks had plans to come to California the following February and was happy to arrange a visit to Stanford. The Rickfords and three of their resident assistants organized two days of programming for Parks that included a visit to Arroyo House, a press conference and reception, and a celebratory gathering at Memorial Auditorium in her honor.

“I was just blown away that this icon of the civil rights movement was coming,” said Rickford, who recounts Parks’ visit in his new memoir, Speaking My Soul: Race, Life and Language (Routledge, 2022), a retelling of his journey from his native Guyana to Stanford.

An icon at Stanford

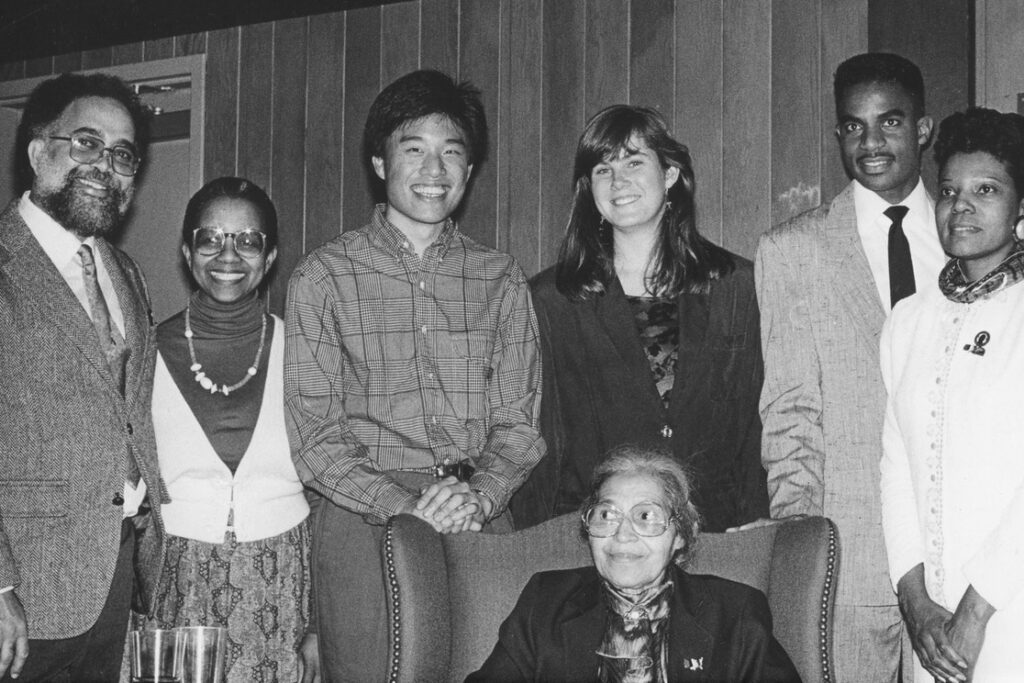

Parks and her assistant arrived at Arroyo House on that Sunday to visit with residents, and privately with the Rickfords.

Parks at the Arroyo House reception, Feb. 18, 1990; From left: John R. Rickford, Angela Rickford, Eric Loh, Ashley Ryan, Rosa Parks (seated), Matt McLeod, and Parks’ assistant Elaine Steele. (Image credit: Courtesy John R. Rickford)

“She came into our little resident fellow apartment, which is next to the dorm,” Rickford said.

When he and his wife introduced Parks to their children, their 5-year-old son unexpectedly jumped into her lap. When the Rickfords quickly objected, Parks dismissed them and embraced the child.

“She really loved kids,” he said.

The press conference took place inside the Arroyo House lounge. About a dozen local reporters arrived to hear Parks describe life under southern racial segregation in the 1950s and the events that sparked the Montgomery Bus Boycott.

Rickford explained that at that time, buses in Montgomery had sections for white passengers in the front, and sections for Black passengers in the back. Black passengers had to enter the front to pay their fare, then immediately exit and reenter at the back entrance. But after they paid and exited, white drivers would often drive forward and make Black passengers chase the bus, just to ridicule them. Drivers would pass by some stops, forcing Black passengers to walk to their destination, or even refuse to pick up Black passengers altogether.

“It was always a very oppressive and humiliating way of life, and it did not seem to be getting better,” Parks said at the press conference, noting that violence – often fatal – was frequently used to perpetuate the oppression.

Parks recounted for the reporters the moments that led up to her famous arrest on Dec. 1, 1955. She also recalled what the bus driver said to her when she refused to give up her seat for a white passenger.

“He told me if I didn’t stand, he was going to have me arrested and I agreed with him that was what he should do,” she said. Two police officers arrived, arrested Parks, and booked her at a local jail.

“I was willing to face whatever consequences I had to, to let it be known that I did not feel I was being treated fairly as a passenger or a person,” she said.

There’s a common misperception that Parks wouldn’t give up her seat simply because she was tired. But Rickford explained that she was involved in political activism, served as a senior adviser to the NAACP Youth Council, and, on that day in 1955, was standing up against racial segregation on the buses.

“She had a very strong political side that I don’t think people often recognize,” Rickford said.

Memorial Auditorium

The “Thank you Rosa Parks,” event took place the following day, Monday, Feb. 19 (Presidents’ Day), in a packed Memorial Auditorium. Rickford estimated the public gathering attracted as many as 1,700 people from across Stanford and the Bay Area.

John and Angela Rickford in the backyard of the Arroyo House resident fellow cottage where they lived and hosted Rosa Parks in 1990. The signed portrait of Parks remains inside Arroyo House 33 years later. (Image credit: Andrew Brodhead)

Attendees from Stanford and the surrounding community took to the stage to give remarks or perform, to celebrate and pay their respects to Parks. At the close of the program, Parks expressed her gratitude for the invitation and spoke briefly about her life and legacy.

“Seeing her and hearing her was a big deal for the audience,” Rickford said.

The event was well-received by students and visitors who traveled to Stanford to see her, and then-President Donald Kennedy wrote a congratulatory note to the Arroyo House residents who organized the event.

Parks’ legacy

Rickford and his wife, Angela, recently visited Arroyo House and the resident fellow’s cottage where they had hosted Parks back in 1990. Pausing at the signed portrait Parks had given Arroyo residents, Rickford reflected on Parks’ enduring legacy and the power of her defiance.

“Various people had tried challenging racial segregation laws in many ways and had been singularly ineffective,” he said. “But she did it in a big way.”

Digitized materials documenting Rosa Parks’ visit to Stanford, including a recording of the press conference, are available in the Stanford Libraries archives.