Stanford human and planetary health course empowers students with tools for change to benefit both human health and the environment

More than 100 students from diverse backgrounds and fields of study were drawn to a fall class exploring the connection between the health of people and the environment, part of a wave of interest in classes about sustainability.

Ben Maines, a third-year Stanford medical student, has been interested in the connection between the natural world and human wellness since his childhood in the woods of Maine, where his family grew its own produce and spent a lot of time outdoors.

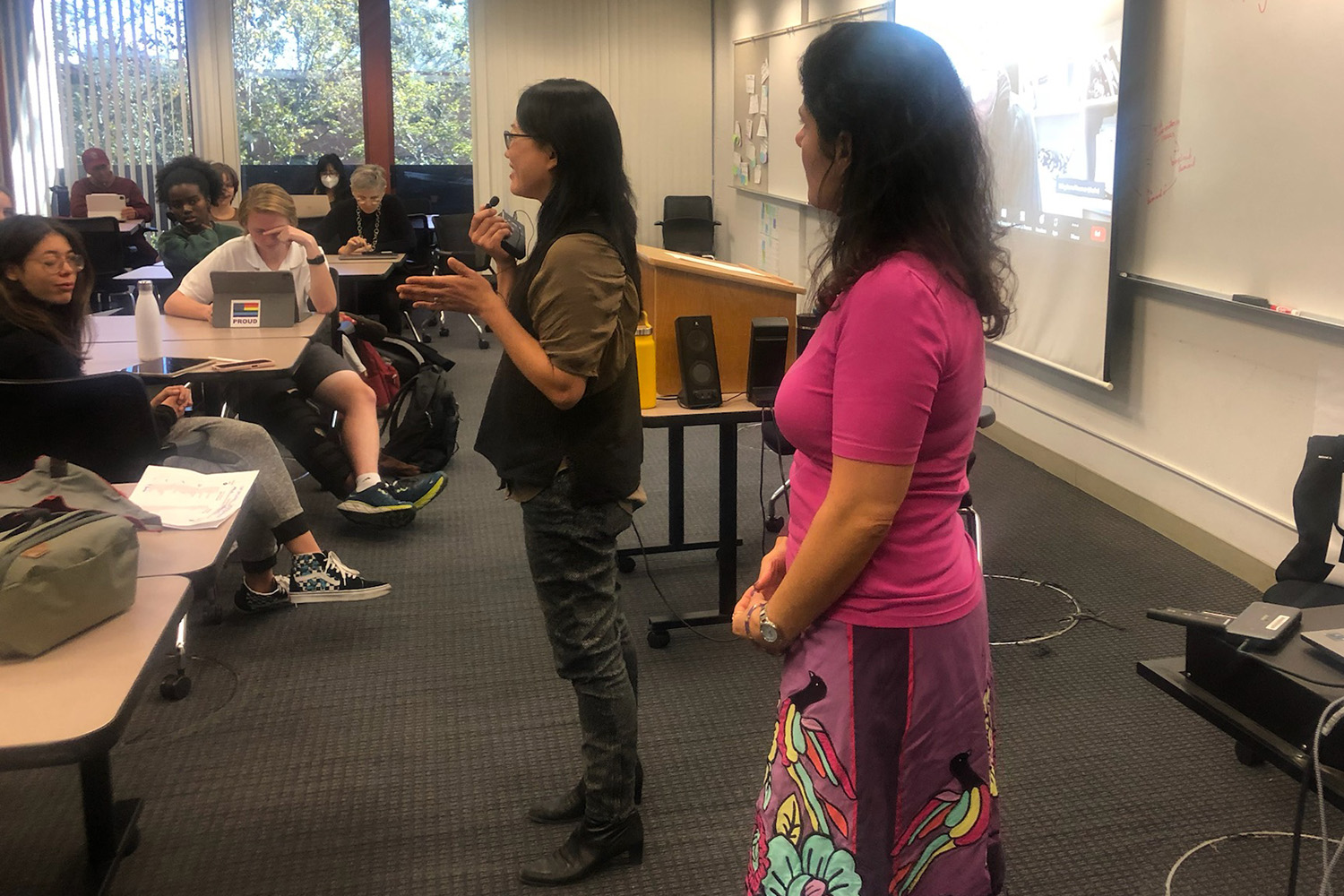

Artist Jean Shin (left) and pediatrics professor Desiree LaBeaud describe their collaboration to raise awareness of the health risks of plastic waste and its connection to infectious disease. (Image credit: Erika Veidis)

“I’ve always had a close connection with the world and ecosystems around me, and a sense of reliance on them for my own well-being,” he said. As a medical student, he became involved in student groups active in climate and health, advocating for the inclusion of climate change in medical curriculum.

Maines sought academic tools and frameworks to better understand the relationship between people, the planet, and health – and how he could use this knowledge to make a difference for his patients. He decided to pursue a master’s degree through the Emmett Interdisciplinary Program in Environment and Resources (E-IPER) alongside his medical degree. As part of these studies he signed up for a fall 2022 course being offered through the Doerr School of Sustainability, Human and Planetary Health. The interdisciplinary course is cross-listed in the medical school, as well as in biology and sociology.

Maines was one of more than 100 students from diverse backgrounds and fields of study who were drawn to the course as the launch of the Doerr School of Sustainability drove heightened interest in classes addressing climate change, its impacts, and solutions.

“This year, we saw a lot of student interest in using a systems thinking approach to see the linkages in how environmental degradation impacts human health, and recognizing the inequities and environmental justice challenges that marginalized communities suffer the most,” said Giulio De Leo, one of four course instructors.

De Leo, professor of oceans and of Earth system science and senior fellow at the Woods Institute for the Environment, launched the class as a mini-course for 12 students in 2018 alongside Kathy Burke, who is now the Human and Planetary Health Lead at the Woods Institute and lecturer at the Doerr School; Steve Luby, associate dean for global health research; and Dr. Susanne Sokolow, executive director of the Stanford Program for Disease Ecology, Health and the Environment (DEHE). At the time, human and planetary health was still an emerging field, kickstarted by a 2015 Rockefeller Foundation – Lancet Commission on the topic.

During the pandemic they converted the course to a full-length offering that drew about 20 students in 2020, and 55 in 2021. This year, they expanded the class capacity to 100 to meet student interest alongside co-instructor Erika Veidis, planetary health program manager at the Stanford Center for Innovation in Global Health.

The course leveraged the wide network and academic community created through three Stanford institutions: DEHE, the Center for Innovation in Global Health, and the Woods Institute for the Environment. Their shared activities underlie the Stanford Doerr School of Sustainability’s Healthy Planet, Healthy People initiative.

The course focused on how to connect knowledge to action, said Burke. She noted that the last section of the course emphasized levers of change and various options for students to engage based on their future studies and interests.

Hope for action

Rebecca Spencer, a graduate student in the Earth Systems program, discovered the course while seeking classes that could shed light on how to contribute to solutions for big issues, like climate change. After sitting in on a class, she was inspired by the instructors’ passion and intrigued by the concept of human and planetary health, which was new to her.

Spencer and her classmates explored human and planetary health through a series of lectures and case study discussions that highlighted problems and potential solutions in four focus areas: climate and health; pollution; infectious diseases and global change; and food systems. Through interactive labs, they explored methods for investigating and taking action.

They learned from Banny Banerjee, director of Stanford ChangeLabs, who highlighted the systems thinking approaches critical to understanding complexity and identifying levers for action, and Paul Saffo, a Stanford-based futurist who illuminated strategies to understand multifaceted challenges and forecast the impacts of solutions. Indigenous leader and physician-scientist Nicole Redvers showcased the power of Indigenous knowledge in addressing planetary health issues, while Desiree LaBeaud, a Stanford pediatric infectious disease specialist and researcher, discussed the connection between ecological changes and infectious disease. She also highlighted policy and community-based solutions, including art installations with recycled plastic waste, a project that will be developed with Stanford artist-in-residence Jean Shin. Luby, a co-instructor, illuminated the power of community partnerships and circular economies to address sustainability and health concerns in low-resourced settings.

Medical student Ben Maines on an outing at Mount Shasta with E-IPER students. (Image credit: Catherine Rocchi)

“Stanford students understand the seriousness of the planetary health problems their generation faces. As instructors, we need to provide them insights and approaches that can help improve the situation,” Luby said.

Burke acknowledged the students’ engagement and involvement: “It was a very community-oriented class, with students sharing viewpoints and ideas for readings that will shape this course in the future.”

For Maines, the course offered a new outlook on a topic that can often feel overwhelming and hopeless. “Before taking the class, I had been in a place of disillusionment about climate change and planetary health – both in the scale of the challenges, and the depth of social and cultural apathy toward them,” he said. “The speakers and readings left me with a sense of hope for action. Don’t get me wrong, I’m still disillusioned, but at least now I feel that there are glimmers of possibility and inspiration in the dark skies of an uncertain future.”

Everything is connected

During the course, students engaged in lengthy group projects delving into issues at the nexus of environment and health and offering real-world solutions, which they presented at the end of the quarter. They took on issues such as antibiotics in aquaculture and the potential consequences for ocean and human health, sea-level rise, and air quality concerns from wildfire smoke. They identified specific groups or stakeholders that could make a difference and proposed practical solutions to these complex challenges.

Veidis said she was inspired by the students’ final presentations, which showcased their sophisticated, systems-based understanding of how to influence change.

“There’s the saying that if you pull a thread, you’ll find it’s connected to the rest of the world,” she said. “The students’ challenge was to winnow down a theory of change and find key levers for impact in a specific planetary health challenge – identifying key stakeholders and how they might be able to influence them.”

For Spencer, the most important takeaway was learning about leverage points at which individuals can influence big systems affecting human and environmental health. “A key point was that everything is connected and very interdisciplinary, that all these factors impact one another,” she said. “I saw that, even as a student, you can take these points and have the power to make change.”

To read all stories about Stanford science, subscribe to the biweekly Stanford Science Digest.