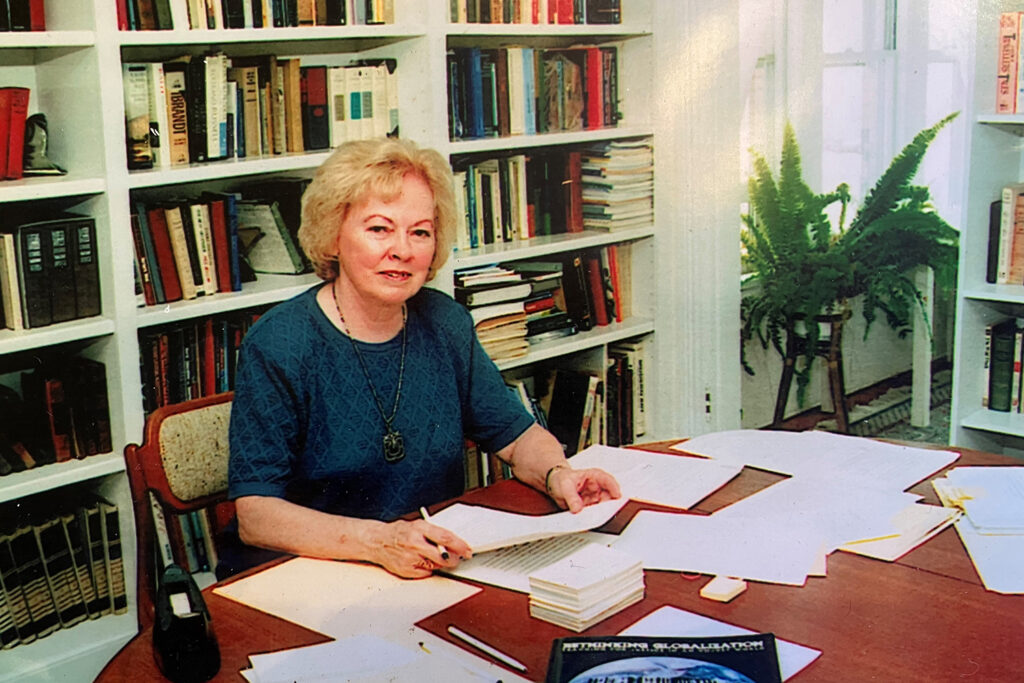

Nel Noddings, feminist philosopher and Stanford education scholar, dies at 93

Noddings, best known for her groundbreaking theory on the ethics of care, was the first woman to serve as dean at any of the professional schools at Stanford.

Nel Noddings, the Lee L. Jacks Professor, Emerita, at Stanford Graduate School of Education (GSE), a feminist educator and philosopher best known for her theory on the ethics of care, died Aug. 25 at her home in Key Largo, Florida. She was 93.

Noddings, who began her career as a mathematics teacher in the 1950s, went on to become one of the world’s most influential scholars in the field of educational philosophy. In developing a comprehensive theory of care, she argued that caring is at the basis of morality and called for reorienting education to put the student-teacher relationship at the center.

At Stanford, in addition to her teaching and research, Noddings directed the Stanford Teacher Education Program (STEP) during a critical stage of its growth. She later held the roles of associate and acting dean of the GSE – and with the latter, in 1993, she became the first woman to serve as dean of any of the professional schools at Stanford.

“Nel was beloved,” said Myra Strober, a professor emerita at the GSE who served as associate dean during Noddings’ term as acting dean. “She was a wonderful human being with an understated, caring style of leadership. And in her quiet way, she made great strides with a feminist view of philosophy and had a huge impact on feminism as a field.”

Rachel Lotan, a professor emerita at the GSE who directed STEP from 1999 to 2014, earned two master’s degrees and a PhD from Stanford and recalled a class Noddings taught as one of the most memorable among the many courses she took. “Nel embodied the ethic of care she introduced, theorized, and wrote about,” she said. “The world will miss her and her teachings.”

School as the center of her life

Noddings, born Nellie Laura Rieth on Jan. 29, 1929, was raised in a working-class family in Irvington, N.J. Neither of her parents advanced beyond ninth grade; her father worked in a manufacturing plant while her mother worked as an office manager throughout Noddings’ upbringing during the Great Depression.

While her family provided a stable and caring environment at home, Noddings became deeply attached to her teachers from a young age, and school became the center of her life. “For me, school was a home,” she recalled in a 2017 interview for the Stanford Historical Society Oral History Program. “Other kids were looking forward to vacation. I was looking forward to going back to school.”

Her close connection to school influenced her to pursue a career in teaching, and she went on to earn her bachelor’s degree in mathematics and physical science from Montclair State Teachers College in 1949. That year she also wed James Noddings, her high school boyfriend; they were married for 63 years, until he died in 2012.

Working as a middle- and high-school math teacher and administrator into the early days of the civil rights movement, Noddings was adamant about bringing social issues into the classroom.

“My closest colleague in the math department said that the best thing to do was to ignore all that and stick right with the curriculum, to show the kids that there was a place of continuity and peace and quiet. … I felt very strongly on the opposite side, that we should talk about the things that were so important, and that the kids were so concerned with,” she said. “I always had a strong reputation as a successful math teacher. The kids did well. But I would drop the quadratic equation in a minute if I felt the kids needed to talk about a social or political problem.”

While she taught, she and her husband started their own family: Noddings gave birth to five children, and the couple adopted three more. Altogether, they brought up 10 children (including two they raised but never formally adopted) – largely while Noddings attended graduate school, first earning a master’s degree in mathematics from Rutgers and then her PhD from Stanford GSE.

When she came to Stanford as a doctoral student, her goal was to go into school administration, ideally to become a superintendent. Then she enrolled in two required courses on the philosophy of education. “As that quarter went along, the house started filling up with philosophy books,” she said. “I was converted.” She switched from curriculum to philosophy.

After earning her PhD in 1973, she briefly joined the faculty at Penn State University and then the University of Chicago before returning to Stanford to teach in 1977.

The student-teacher relationship

As a professor and director of STEP, Noddings continued to practice her conviction that schools should be a place where students can explore issues beyond the standard curriculum, and where students and teachers build meaningful, caring relationships.

Denis Phillips, an emeritus professor at the GSE, recalled a seminar the two held in the evenings at their own homes, with students reclining in easy chairs or on pillows next to the fireplace. In another course during the late 1980s or early 90s, Noddings asked Phillips to show up to guest lecture one afternoon wearing a dress, without comment, prompting a class discussion after his departure about gender roles and the social acceptability of his attire.

Noddings served as associate dean of the GSE during Marshall “Mike” Smith’s tenure, and when he left the faculty to join the U.S. Department of Education in 1993, Noddings was appointed acting dean, becoming the first woman to serve as dean of any of the professional schools at Stanford.

When she was named the Lee L. Jacks Professor in 1994, she also became the first woman to hold an endowed chair at the GSE.

The ethics of care

Noddings authored more than 20 books and hundreds of articles on topics including school reform, mathematics teaching and learning, and the ethics of care. In her landmark book, Caring: A Feminine Approach to Ethics and Moral Education, published in 1984, she explored what it means to care and be cared for, arguing that caring is at the basis of moral action and should be central to the educational system. (In a subsequent edition of the book, having fielded criticism for the use of the word feminine in the subtitle, she replaced it with relational.)

After leaving Stanford, Noddings taught at Columbia University and Colgate University. She also served as president of the Philosophy of Education Society, the Dewey Society (named for philosopher and educational reformer John Dewey), and the National Academy of Education. In addition, she chaired the ethics committee for the American Educational Research Association, where she spearheaded the writing of ethical guidelines for the field.

She is survived by nine children, more than 30 grandchildren, and dozens of great-grandchildren.

A celebration of Nel Noddings’ life will be held on Friday, Nov. 18, at 1:30 p.m. at the Center for Education Research at Stanford (CERAS), 520 Galvez Mall, Room 101.