Stanford course experiments with ways to recapture dynamic elements of in-class teaching

A new Zoom-based platform developed at Stanford enables instructors to directly engage more with students and promote active learning during large lectures.

As the coronavirus pandemic has smoldered on, students and faculty alike have adapted to online learning over video platforms such as Zoom – as well as the format’s limitations, including an impersonal quality that can pervade large sessions with many participants. Yet for a large, interdisciplinary course like Stanford University’s CS 182: Ethics, Public Policy, and Technological Change that thrives upon dynamic interactions among instructors and attendees, the status quo simply wouldn’t do.

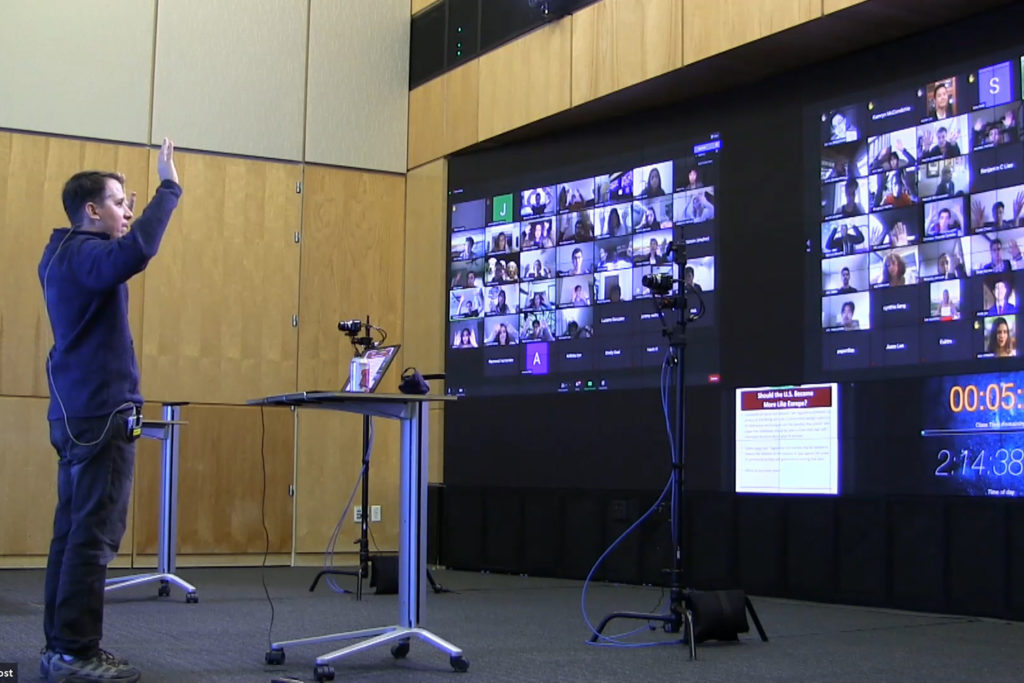

Jeremy Weinstein giving a lecture with the room viewed from the overhead cam. The videowall is shown, as well as the three stationary floor cameras. (Image credit: Bob Smith)

Last fall, the course faculty approached Stanford academic technologist Bob Smith about overcoming these limitations while also adhering to the strict COVID-19 protocols on campus. The goal was to create a learning environment that could accommodate hundreds of live attendees, boost virtual classroom engagement, facilitate dialogue and energize academic exchange. Smith’s months-long effort culminated in a pioneering virtual learning format that not only has successfully driven CS 182 over this past winter quarter, but also should empower enhanced virtual learning beyond the pandemic as well.

“When we first confronted what it would mean to offer this CS 182 course in teach- and learn-from-home conditions, we saw that the traditional virtual classroom format could not provide the level of interactivity and pedagogical approach we were after,” said one of the course’s instructors, Rob Reich, a professor in Stanford’s Department of Political Science and director of the Center for Ethics in Society. “Thankfully, Bob Smith really delivered and we feel that this learning platform he’s built from scratch holds a lot of promise for other courses.”

Smith’s platform leverages Zoom’s capabilities to the max, using unconventional ideas to unleash new functionality. The enhanced virtual classroom experience involves faculty coming to campus (while adhering to COVID-19 precautions) and giving course lectures from a special room outfitted with a vast, 32-foot-wide by 8-foot-high videowall. Projected onto the videowall is a tiled display of students on their device screens over Zoom. Live video feeds from stationary cameras placed in the room enable the faculty to interact with students on the videowall. A unique aspect of the platform is that it empanels a small group of students on a rotating basis to engage in direct one-on-one discussions with instructors during class. The learning platform additionally mixes in breakout rooms where a handful of students can discuss topics du jour, plus live polling and chat features – all essential elements for promoting engaged learning.

“Since we all went onto Zoom when the pandemic started, I’ve been trying to re-create that buzz, that rush of adrenaline that instructors and students both feel from learning, and which is difficult to achieve when everyone’s sitting around, passively watching a screen,” said Jeremy Weinstein, a professor of political science and one of the three instructors, alongside Reich and Mehran Sahami, associate chair for education in the Computer Science department.

“The fact that with this platform, I can stand in a room and walk up to a student and go back and forth with them and see their facial expressions, and both parties feel genuinely engaged – that’s a gamechanger,” he added.

Fostering dynamic exchanges

Taken by most undergraduates majoring in computer science, CS 182 is popular across several majors and often enrolls upwards of 250 students. An interdisciplinary course, CS 182 is taught by faculty in the Schools of Humanities and Sciences as well as Engineering.

“In CS 182, we encourage students to adopt and defend positions on important matters of technological development at the intersection of ethics, public policy and technology,” Weinstein said.

Example topics include algorithmic fairness, data privacy and civil liberties, the ethics of autonomous systems, and free expression on social media platforms – concepts made all the more relevant given Stanford’s role in educating many leaders in local and national governments, NGOs, nonprofits, education and technology.

The initial challenge the faculty faced in translating the course online was Zoom’s limits on breakout rooms. The large class size meant the rooms would contain too many participants for quality, small-group discussion. Smith then came up with the innovation of splitting the class into three appropriately sized, separate, yet fully integrated Zoom sessions – which he nicknamed Rock, Paper and Scissors.

From there, Smith gave life to the instructors’ desire for dialogue by empaneling a rotating selection of students in the Rock session each class (CS 182 meets three times a week) who can interact more directly with the instructor. For example, the students in Rock might be called upon and asked to share their thoughts, and their interaction with the professors is then broadcast to all the other students in real-time.

“The faculty described to me that for large lectures, standard virtual learning setups can be like ‘teaching to the void’,” said Smith, the director of classroom innovation in the Office of the Vice Provost for Student Affairs. “They sought an affordable, in-house way to augment interactivity, and we’ve come up with something we’re very pleased with.”

Devising the setup

Smith started putting these ideas into practice at the Peter Wallenberg Learning Theater in Wallenberg Hall on campus, a two-story room equipped with a giant videowall that makes it a popular space for teaching and research. To make the Learning Theater work for his purposes, Smith had to string countless meters of wire between multiple computers, cameras and other equipment to support the Zoom sessions’ video and audio, and link everything to the display wall. The entire setup is managed in a control room located on the second floor overlooking the space.

During class, a teaching assistant in the control room toggles between video feeds from five cameras, mixing up the viewpoints that are pumped out over Zoom to attendees, akin to a live sporting event. Anywhere from one to three of these cameras – depending upon how many socially distanced faculty might be teaching the class that day – are affixed to tripods in front of lecterns in the room, providing a straight-on view of the lecturers. A camera is also positioned off to the side and slightly behind the lecturer, showing the videowall with the lecturer facing it. “We switch up the perspective intentionally so the lecturer does not appear as confrontational as they might if the camera constantly faced them dead-on, and this also lets students see themselves up there on the videowall,” Smith explained. Another camera placed high upon an overhead lighting rail provides an ambient view of the room and its floorspace.

On the videowall itself, the empaneled section might show 45 students from the Rock class on their device screens in a mosaic splayed across a large Zoom gallery. Meanwhile, the Paper and Scissors section students are also visible, but appear as smaller screen tiles in separate areas of the videowall. Along the videowall’s bottom, three display sections show lecture slides to the instructor (which is also visible on the student’s screens), a clock so the instructor can keep track of time, and finally, an enlarged Google Doc. Teaching assistants can update the Doc in real time with, for example, questions from students. In addition, all the classes are recorded so students can engage fully and then later go back and take notes or review the day’s discussions.

A promising new modality

Stanford students have reacted positively to the enhanced online learning experience. “These lectures are about engaging your thinking and critically examining your own ideas, so the synchronous learning aspect is very important,” said Michael Herrera, a junior-year student majoring in symbolic systems. “The way the setup empanels around 40 people I think is a really powerful idea.”

Muskan Shafat, a senior-year political science major with a concentration in data science, likewise has enjoyed the Rock empaneling design. “When you know you’re going to be in Rock, you have more leverage to interact with the professor,” she said, further noting that “the teachers in CS 182 are really doing an amazing job.”

Peter Herminio Maldonado, a senior-year computer science major, said he appreciates how the platform recaptures elements of in-class teaching’s dynamism that are otherwise lost in large lectures over standard Zoom. “I like how the setup brings some of the performance back from campus lectures,” he said.

Weinstein already plans to use Smith’s active learning platform for a political science course in spring quarter, and other faculty at Stanford have expressed interest as well. The instructors also believe that the platform represents an excellent opportunity for Stanford teachers to reach audiences off-campus. For now, only the room in Wallenberg Hall is equipped to run the platform, but Reich said he hopes Stanford will invest in multiple classroom spaces to expand its adoption.

“I think there is major upside here for when we return to class as normal, but we still want to reach people beyond the classroom,” Reich said.