|

Activism more than lectures prompts teen

smokers to cut back on cigarettes

A novel approach showed that teens reduced their own smoking while

trying to persuade others to quit

By SUSAN IPAKTCHIAN

Scare tactics and lectures don’t persuade

teenage smokers to change their habits, but engaging them as

anti-smoking activists does, say School of Medicine

researchers.

A study involving 10 Bay Area continuation, or alternative, high

schools found that among students who were regular smokers, those

who engaged in anti-tobacco advocacy efforts significantly reduced

their own cigarette use compared with teens in traditional drug

abuse prevention classes. What the researchers found even more

encouraging was that the decrease continued six months later

– a rarity in the efforts to reduce cigarette use among

teens.

“The real, sustained change we saw is different from most

other studies on teenage smoking. In past studies where smoking

behaviors changed, the effect was very transitory,” said

Marilyn Winkleby, PhD, associate professor of medicine at the

Stanford Prevention Research Center and senior author of the paper

published in the March issue of the Archives of Pediatrics and

Adolescent Medicine.

Smoking remains the leading cause of illness, disability and death

in the United States, with adolescents being the most likely to

begin using tobacco, Winkleby said. In 2001, 36 percent of high

school students reported smoking cigarettes within the past 30

days. That rate is closer to 70 percent at continuation high

schools, which serve students who are at risk of failing or

dropping out of regular school or have been removed from their

school for other reasons.

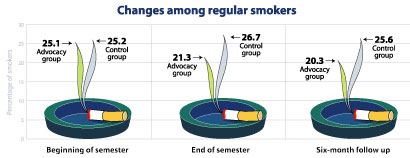

In comparing teen smokers

in traditional prevention classes to those who were part of an

anti-tobacco advocacy program, researchers found that cigarette use

dropped dramatically for those in the advocacy program. The first

panel shows the number of students who smoked a pack or more a week

before beginning each program, while the second and third panels

show the changes at the end of the training and again six months

later. Graphic: Amy

Feldman

Ten continuation high schools in the San Francisco/San Jose area

were selected for the study, with five randomly assigned to a new

anti-tobacco advocacy curriculum and the other five to an existing

curriculum on drug and alcohol abuse prevention. Juniors and

seniors were recruited during each of four semesters to attend a

weekly class for which they received credit.

Students were surveyed to determine their tobacco use at the

beginning of each semester. Roughly 35 percent were non-smokers

(never or former smokers), 40 percent were light smokers (less than

a pack a week) and 25 percent were regular smokers (a pack or more

a week). Students breathed into a carbon-monoxide monitor to

confirm their reported level of smoking. At the end of the

semesters and again six months later, they were re-surveyed about

their tobacco use.

For students in the advocacy curriculum the most significant change

was among regular smokers, whose smoking decreased by 3.8 percent

at the end of the semester and an additional 1 percent six months

later. By comparison, the rate among regular smokers in the drug

and alcohol prevention curriculum increased by 1.5 percent at the

end of the semester. “Without any intervention, you would

expect to see even larger increases in smoking during a period of

six months to a year,” Winkleby said. “The fact that

the regular smokers in the advocacy curriculum made a significant

decrease in their usage and sustained that behavior for another six

months is very encouraging.”

The goal of the advocacy program was to heighten students’

awareness of the cues in their school and community environments

that promote cigarette use, Winkleby said. “It’s not

the traditional approach of providing individuals with information

to get them to change their own behavior. It’s an indirect

way to bring about behavior change by making students aware of the

social context of smoking behavior.”

Students learned about tobacco availability and advertising

strategies, and assessed tobacco promotion in their communities.

“Most of them were surprised and then angry when they

realized how extensive it was,” Winkleby said.

“Teenagers don’t like it when other people try to

influence them.”

The students then developed, implemented and evaluated advocacy

projects that included: forming a task force to enforce campus

smoking bans; increasing store compliance with laws limiting

tobacco ads on building exteriors; eliminating magazines with

cigarette ads from medical and dental offices; and convincing city

council members to decline campaign contributions from tobacco

companies.

The drug and alcohol prevention classes for the five other schools

were adapted from a highly regarded curriculum that had proved

effective among continuation students, Winkleby said. It focused on

health motivation, social skills and decision-making regarding drug

and alcohol use.

The success of the advocacy approach in changing smoking behavior

makes it a strategy worth evaluating for other health-related

issues, such as helping teens make better food and exercise

choices, Winkleby said.

Other co-authors of the study include statistical computer analyst

David Ahn, PhD, and Joel Killen, PhD, professor (research) of

medicine at the Stanford Prevention Research Center. The study was

funded by a grant from the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

Packard residents fight Hollywood puffing

Junior pediatric residents at Lucile Packard Children’s

Hospital are setting their sights on teen smoking, taking aim at a

big target: Hollywood.

A study that appeared in The Lancet last June said that

adolescents who see movie characters smoking are more likely to

pick up the habit themselves than are adolescents without the

exposure. Other research has shown that the number of movies

portraying smoking is on the rise. The residents are working with

the Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids and the national Smoke Free

Movies organization to address the problem.

“Smoking in movies is a significant health threat to

children,” said Lisa Chamberlain, MD, who supervises

Packard’s advocacy training course for residents and is one

of the Smoke Free Movies project leaders. “We want Hollywood

to take notice.”

Packard residents are meeting with community leaders, school boards

and health-care providers to gather signatures on letters and

petitions along with empty cigarette cartons as part of an

aggressive education and awareness plan. In June, the residents

will deliver these signatures to some of Hollywood’s most

influential moviemakers.

The hope? Filmmakers will reduce smoking in movies and voluntarily

assign R-ratings for movies that contain smoking scenes.

The Packard residents are also educating area students on the

dangers of youth smoking and how tobacco companies benefit from

smoking in movies. “The community is learning that movie

smoking is a serious health issue,” said Seth Ammerman, MD,

assistant professor in pediatrics and co-leader of the project with

Chamberlain. “It’s clear that children who are exposed

to smoking and smoking marketing in movies are more likely to try

it themselves, and the residents are doing something about

it.” – Robert Dicks

|