|

Low brain activity linked to protein

levels in disorder

Fragile X syndrome

is marked by autism-like symptoms

By CZERNE M. REID

People with fragile X syndrome, the most common

inherited developmental disability, have reduced blood levels of a

protein vital for brain development and function, researchers at

the School of Medicine have found. These lowered levels are linked

to abnormal activity patterns in the brain.

“It is exciting to think that a biological marker we can

measure in the blood is correlated with vital brain

function,” said Allan Reiss, MD, professor and director of

the Stanford Psychiatry Neuroimaging Laboratory and Behavioral

Neurogenetics Research Center in the Department of Psychiatry and

Behavioral Sciences and the study's senior author.

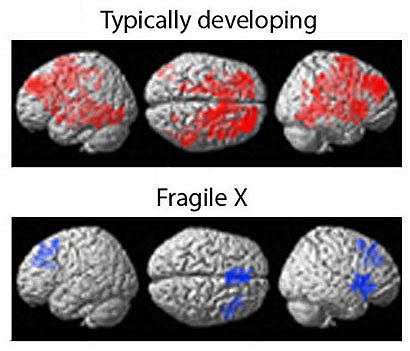

These sets

of images show brain regions where there was significant activation

during the “response inhibition” tasks used to compare

activity in fragile X brains (blue) with typically developing

brains (red). Photo: Courtesy of

Vinod Menon

Additionally, in people with fragile X syndrome, researchers found

that background brain activity outside the realm of problem solving

does not decrease as expected when the individual is confronted

with a complex task. In unaffected people, the brain smoothly

redirects resources to other tasks as needed. This may explain why

people with fragile X can't produce cognitive resources when

needed.

The findings, published March 1 in the Proceedings of the

National Academy of Sciences, will enable a more targeted

approach to the development of treatments for the disorder.

Fragile X syndrome is so named because it results from a mutation

of a gene at a “fragile site” on the X chromosome where

structural gaps may occur. It affects roughly 1 in 3,600 males and

1 in 4,000 to 6,000 females, according to the National Fragile X

Foundation.

The mutation arises when a repetitive DNA segment of a gene known

as FMR1 expands up to hundreds or thousands of times. The FMR1 gene

normally produces fragile X mental retardation protein, which

regulates the production of other proteins controlling how nerve

synapses grow and change in response to learning.

Males with fragile X syndrome produce little or no fragile X

protein. They also have severe manifestations of the disease,

including autistic-like behaviors, hyperactivity and mental

retardation. Affected females often have less extreme symptoms such

as attention deficit, shyness, anxiety and learning problems,

although some may show autistic behavior and mental

retardation.

Such a broad spectrum of severity in females corresponds to a wide

range of brain activation patterns and blood levels of fragile X

protein. This range makes females particularly fitting subjects for

studying the association between the protein levels and brain

activity in individuals with fragile X syndrome.

“The effect of genetic factors on brain function is a topic

of increasing interest within the field of cognitive neuroscience,

and fragile X syndrome provides an excellent model to investigate

the effect of a single gene on human brain function” said

first author Vinod Menon, PhD, associate professor of psychiatry

and behavioral sciences and a member of Stanford's neurosciences

program.

Menon, Reiss and colleagues examined whether reductions in brain

activation are correlated with levels of fragile X mental

retardation protein in the blood. In previous studies the

researchers had shown that individuals with performance deficits

had reduced brain activity in regions known to be associated with

the tasks being performed. They conducted the current study to shed

light on whether the reduced brain activity observed was simply a

function of poor performance or the result of faulty neural

processing.

The study, funded by the National Institutes of Health with support

from the Canel Family Fund, observed 18 females ages 10-22 who had

the gene mutation that causes fragile X syndrome, and for

comparison, 16 typically developing age-matched females. Study

subjects performed a series of tasks while undergoing an MRI that

allows researchers to monitor brain activity. The method tracks

changes in blood oxygen levels as a marker for changes in blood

flow that, in turn, are closely correlated to nerve cell activity

in the brain.

The so-called response inhibition task researchers used was simple,

addressing the ability to control impulsive behavior. Subjects were

shown different letters of the alphabet that flashed one at a time

on a computer screen. They were asked to respond by pressing a key

in every case except when they saw the letter X. The first task was

a “Go” task, in which the letter X never appeared and

in this way subjects were allowed to build up a tendency to

respond. Immediately afterward, subjects performed a “Go/No

Go” task in which the letter X did appear in the lineup, at

which point the subject had to control the previously built impulse

to respond. Statistical correlations were made between observed

reduction in brain activity compared with typically developing

individuals and the levels of fragile X mental retardation protein

found in blood samples taken from each subject.

Individuals with fragile X syndrome performed the response

inhibition task as well as normally developing people, so the

observed differences in brain activity could not be attributed

simply to performance deficits. Among the participants with fragile

X, brain activity decreased in key areas involved in response

inhibition in proportion to fragile X protein levels. “We are

particularly excited to have a marker for this condition that gives

us a tool to begin to query associations across multiple scientific

levels including genetic, brain function and behavior,” said

Reiss. “The study brings neuroscience and psychiatry together

in a unique way.”

The work is part of a comprehensive research program at Stanford

directed by Reiss and devoted to studying fragile X syndrome and

other genetic and neurodevelopmental disorders that affect

learning, behavior and development in children. The research team

plans to expand brain imaging research to test other cognitive and

behavioral functions with the disorder, integrating knowledge

gained from genetic, physiological and behavioral studies. They are

recruiting preschoolers, children and adolescents for ongoing

studies to determine, among other things, the timing, amount and

type of effective interventions.

Individuals with fragile X syndrome or other causes of

developmental disability are encouraged to participate in this

study. Call (888) 411-2672 or e-mail vanstone@stanford.edu for more

information.

|

Laughter, like drugs, tickles brain's reward center

(12/10/03)

Pre-implantation genetic diagnosis offers hope but prompts ethical

concerns (3/3/04)

|