Tiny

‘molecular motors’ shed light on how cells carry out

their functions

Interdisciplinary approach blended physics and

biology to arrive at explanation for cellular order

By MITZI BAKER

Every cell in the body has what James Spudich,

PhD, calls “a dynamic city plan” comprised of molecular

highways, construction crews, street signs, motor cars, fuel and

exhaust.

Maintenance of this highly organized structure is fundamental to

the development and function of all cells, Spudich says, and much

of it can be understood by figuring out how molecular motors do the

work to keep cells orderly.

Spudich, biochemistry professor at the School of Medicine, and

Stanford physics graduate student David M. Altman reported in the

March 5 issue of Cell how a type of molecular motor

provides the rigidity needed by the tiny sensors in the inner ear

to respond to sound. They found that this motor creates the proper

amount of tension in the sensors and anchors itself to maintain

that tension.

“Our general feeling is that tension-sensitive machines are

at the heart of the dynamic city plan,” said Spudich.

Their National Institutes of Health-funded study has implications

far beyond how an obscure molecule provides rigidity for a protein

in the inner ear. A motor able to create structural changes by

taking up slack in proteins and clamping down so that they remain

in a rigid position may help explain many intricacies of cellular

organization, such as how chromosomes line up and separate during

cell division.

“Studies like this allow you to understand enough details of

these motors to design small molecules to affect their

function,” said Spudich, who is also the Douglass M. and Nola

Leishman Professor of Cardiovascular Disease. Toward this end he

has co-founded a company, Cytokinetics, in hopes of creating drugs

that selectively target molecular motors involved in cancer and

cardiovascular disease.

For years, Spudich’s lab has studied molecular motors called

myosins, proteins that carry out cellular motion by attaching to

and “walking” along fibers of actin. The interaction of

actin and myosin is the mechanism behind cell actions such as

muscle contractions, the pinching off of two daughter cells from a

mother cell during division and the hauling of cargo molecules

around in a cell.

Of the 18 types of myosin molecules, their current findings examine

myosin VI, thought to be responsible for setting the tension for

stereocilia, actin-filled rods on the sound-sensing hair cells of

the inner ear. A defect in myosin VI results in deafness.

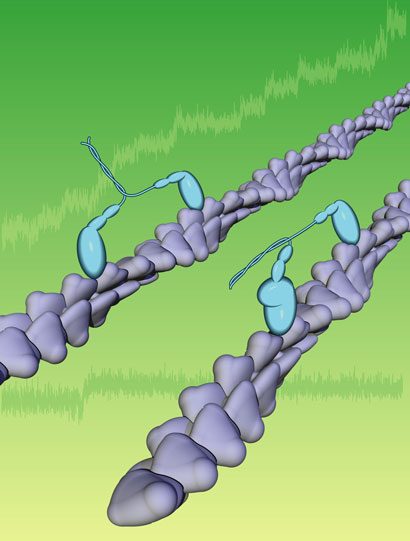

A myosin

molecular motor attaches to a portion of an actin filament and

walks down its length. If the myosin tail is carrying a load, it

stops walking and turns into a clamp when a certain level of

tension is reached. Researchers think that this clamping mechanism

can explain much of how cells maintain their internal structural

organization. Illustration:

Courtesy of Spudich Lab

Although it was known that myosin moves along actin fibers, it had

never previously been demonstrated how myosin could function as an

anchor or a clamp. To study this, Spudich and Altman needed

techniques beyond the realm of biology.

“This is a problem for physicists who think in terms of

forces and putting a load on a system,” said Spudich. Altman

specializes in optical tweezers, a focused laser that allows the

manipulation of microscopic beads, and provided the required

physics know-how by applying his expertise to studying myosin

activity precisely.

The Cell paper includes a number of complex equations

describing how the myosin VI anchor works, but the researchers have

easily simplified the concept: think of the palm of an open hand as

the hair cell and the fingers as the stereocilia. Myosin VI has two

legs as well as a tail, which can bind to other things.

The researchers think the myosin VI tail in the hair cell binds to

the webbing between the fingers – the cell membrane between

the stereocilia – and then as the legs walk across the palm

(the hair cell) it pulls the webbing between the fingers taut which

makes the stereocilia rigid.

As the motor continues walking, the taut membrane strains the motor

and distorts its shape, which turns the motor into an anchor. If

the webbing/membrane becomes slack again, the motor regains its

normal shape and begins walking again. It continues walking until

the membrane becomes taut again.

“You can imagine that if a motor like this didn’t

stall, it would end up continuing to burn energy in the cell and

would keep pulling this membrane, but it would be wasting a lot of

energy,” said Altman, who is first author of the paper.

“So this change has made it a smart and efficient

motor.”

“The sophistication of what David has been able to do here in

terms of looking at a single molecule and how it behaves is

unusual,” Spudich noted. “There are very few proteins

in biology that have been analyzed and understood down to this

level.”

Altman is now looking at defective myosin VI that causes deafness

in hopes of learning even more about the precise refinement of the

molecular motor.

Studies of molecular motors are fundamental to understanding all of

cell biology, said Spudich, and require a multi-faceted approach

combining the input of several disciplines.

|