Stanford Report, January 14, 2004

Media attention and an engaged public influence physician presribing patterns

By SUSAN IPAKTCHIAN

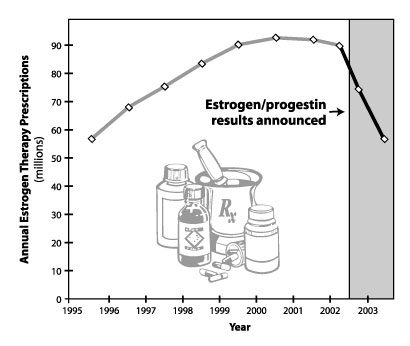

The dramatic drop in prescriptions for postmenopausal hormone replacement therapy after the risks of long-term estrogen/progestin use were announced suggests physicians respond more readily to new clinical evidence than previously observed, researchers say.However, the researchers add that a study of the impact of hormone therapy findings along with a separate analysis of a clinical trial involving a blood pressure medication indicate that physician response may be faster and more complete when the evidence is widely publicized through the news media and discussed by the general public.

After a widely publicized announcement on health risks of certain

hormone therapy regimens, researchers tracked a dramatic drop in

prescriptions for the estrogen/progestin combination. Chart: Amy

Feldman

Randall Stafford, MD, PhD, assistant professor of medicine at the Stanford Prevention Research Center and senior author of the two studies, said the findings suggest that consumers and the media play a pivotal role — one that is often overlooked by scientists — in establishing the pace at which clinical trial findings are translated into actions that improve public health.

"Our research provides reassurance that physicians will respond to new evidence," Stafford said. "Our work doesn’t necessarily contradict past studies, which cast doubt on that process, but it illustrates the conditions under which physicians are most likely to respond. Special circumstances may be required to engender the response that we observed."

The two studies appeared in the Jan 7 issue of the Journal of the American Medical Association.

Stafford said he and his colleagues wanted to examine whether evidence that a drug did more harm than good spurred physicians to change their practices. "In the ideal, medicine should be based on the most up-to-date clinical information that has solid evidence behind it," he said. "Yet past studies indicate that physicians don’t necessarily switch their practices either completely or rapidly in response to new evidence."

For both studies, Stafford and his colleagues analyzed a national database to determine the number of prescriptions filled by pharmacies for the drugs in question. They also used a national survey of office-based physicians to determine the number of office visits at which the medications were either newly prescribed or continued. The combination of data helped them track changes in physician practice since the mid-1990s.

In the year following the July 2002 announcement about the risks of long-term estrogen/progestin use, the total number of hormone therapy prescriptions dropped by 38 percent — reversing in one year the growth that had occurred over the previous seven years, the Stanford study showed. The researchers found that in 1995 there were 58 million hormone therapy prescriptions for 10 million women, increasing to 89 million prescriptions for 15 million women by June 2002. Based on data for the first seven months of 2003, the researchers estimate the year’s numbers will decrease to 57 million prescriptions for 9.5 million women.

The estrogen/progestin findings dashed long-held beliefs that hormone-replacement therapy, or HRT, offered protection against heart disease in addition to its intended use of relieving postmenopausal symptoms. The multiyear trial was an effort to assess the efficacy of a variety of HRT regimens. The portion dealing with the estrogen/progestin combination was halted early when researchers for the federally funded Women’s Health Initiative became disturbed by a higher incidence of heart attacks, breast cancer, stroke and blood clots among participants.

Of the various HRT medications, the Stanford study found that the largest decline was in the estrogen/progestin combination — a 56 percent decrease compared to 2002 levels. The magnitude of the potential health benefits resulting from those changes is astonishing, Stafford said. The researchers estimated that in 2001 a total of 14,500 cases of heart disease, breast cancer, stroke and blood clots were due to estrogen/progestin use. Based on the 2003 data, they estimate the number will decline to 6,500 cases.

"A very large population uses these drugs and has been positively affected by the changes in practice that have come about," Stafford said.

The hypertension study dealing with a class of drug known as alpha-blockers found that physician response, while positive, was less dramatic and less rapid. In that clinical trial, researchers compared four types of medications for treating high blood pressure: an alpha-blocker, an ACE inhibitor, a calcium-channel blocker and a diuretic. The alpha-blocker portion was halted early when researchers found that those taking the medication had a higher rate of heart failure.

Although prescriptions for the alpha-blocker, known as doxazosin, decreased after the March 2000 announcement about the heart-failure risks, Stafford and his colleagues found that physician response wasn’t as rapid or as complete as might have been expected. Alpha-blocker prescriptions peaked in the fourth quarter of 1999 at nearly 4.4 million and declined to 4.2 million in the first quarter of 2000 when the clinical trial results were announced. Prescriptions continued to decline, reaching a low of 3.3 million in the fourth quarter of 2002. Although there was a 54 percent decline in alpha-blocker use between 1999 and 2002, "these changes took place over several years rather than several months as we saw with hormone therapy," Stafford said. He added that other factors — such as the availability of a cheaper, generic form of doxazosin in October 2000 — may have slowed the response.

Another factor may be the publicity the trials received, Stafford said. Although the media reported the results of the alpha-blocker study, the attention given to the HRT findings was unprecedented. "There is probably no other example of a clinical trial having that much visibility," he said.

"One of our conclusions is that for physicians to respond to clinical trial evidence, it has to leave the professional arena and become a topic of public conversation," Stafford added. "That suggests a remarkably important role for the consumers as well as the media. I think people considering health policy don’t often give credence to that level of input. For science to be successful, it has to deal with the implications beyond just the scientific portion."

The role played by consumers reacting to the HRT findings was also significant. Adam Hersh, MD, PhD, a former postdoctoral scholar at Stanford and first author of the HRT study, said women receiving the medications are generally older, well-educated and take a great deal of responsibility for their health. "The rapid, significant response reflects a population of women who are very tuned in to their health and are willing to make this kind of change," he said.

Stafford pointed out that research into the impact of clinical trial evidence is relatively rare, making it difficult to know whether new scientific findings are being translated into actions that benefit public health. "There are some critical steps in the process that clearly aren’t being addressed," Stafford said.

Marcia Stefanick, PhD, professor (research) of medicine, who chaired the national steering committee for the Women’s Health Initiative study, was also a co-author of the HRT paper. The other Stanford authors on the alpha-blocker study are research assistant Tseday Alehegn and research associate Jun Ma, MD, PhD.

![]()

![]()

Hormone-replacement therapy study abruptly halted (7/10/02)

Medications underused in treating heart disease (1/8/03)

Study indicates physicians, patients overly rely on antibiotics for sore throats (9/19/01)