Aggressive

form of prostate cancer ID’d by test

Finding may lead to better diagnostic tools for

disease

By MITZI BAKER

Prostate cancer is often a slow-grower that

doesn’t spread. In some cases, however, a deadly migration of

cancer cells invades other parts of the body. School of Medicine

researchers have now found a way to distinguish between the two

forms early, which may one day provide a test to determine when

invasive treatment is the best option.

Urology postdoctoral scholar Jacques Lapointe, MD, PhD, working

with senior study investigators Jonathan Pollack, MD, PhD,

assistant professor of pathology, and James Brooks, MD, assistant

professor of urology, scanned thousands of genes in normal and

diseased prostates and discovered that as few as two specific genes

appear to indicate which tumors will be aggressive and which will

not. Their findings were published in the Jan. 20 issue of the

Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

“It is the first time we’ve been able to take tumors

that generally appear the same under the microscope and say that we

can see differences that appear useful in predicting how these

patients will fare,” said Pollack. This work is “early

translational research,” he emphasized, and will need to be

validated by other groups and through prospective clinical

trials.

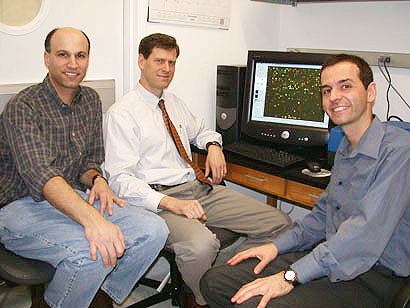

Jonathan Pollack, MD, PhD

(from left), James Brooks, MD, and Jacques Lapointe, MD, PhD, take

a break from studying microarray data identifying genes that

determine whether a case of prostate cancer will be slow-growing or

aggressive. Photo: Mitzi

Baker

Current techniques for estimating the severity of prostate cancer

include measuring the level of prostate specific antigen, or PSA,

and determining tumor stage and grade. These methods, said

Lapointe, provide limited information about both the progression of

the disease and the best course of action.

“We have the PSA blood test, which is not without

faults,” said Brooks, who provided prostate samples from his

patients who consented for the study. He explained that while the

PSA test has proved to be a useful tool in screening men for

prostate cancer, a number of less dangerous conditions can cause

the level of PSA to rise, which has opened controversy over the

test’s usefulness. An easily detectable indicator that not

only unequivocally tells if cancer is present but also how

aggressive it is would be ideal, he noted.

Using microarrays -- glass slides carrying more than 26,000 DNA

spots, each representing a different gene -- the group profiled

gene expression in 112 prostate samples to study the differences

between normal tissue and tumor tissue. They discovered that the

cancers fell into one of three subtypes based on which genes were

turned on or off. Two of these subtypes were associated with more

aggressive cancers.

Interested in streamlining the identification process, they tried

using only a couple of the genes that appeared to indicate either a

more or less aggressive type of tumor to use as markers. They chose

the genes MUC1 and AZGP1 and used a simple antibody test to screen

225 archived prostate samples that had accompanying information

about how each patient had fared on average eight years after their

prostates were removed.

Although there are hundreds of genes that differentiate the

subtypes on the molecular level, the group found that those two

genes captured a significant amount of this information. “We

have shown that these markers predict outcome very well,”

said Pollack. “These markers improve our predictions for the

recurrence of tumors months or years after surgery over and above

anything available now.”

Since as few as two markers are effective at predicting how serious

a tumor a man may have, the simple antibody test could someday be

used clinically to screen for those markers. “It’s much

easier to stain for two antibodies than it is to perform a DNA

microarray,” said Pollack. “This test has the potential

to provide clinicians with more information about how to treat

tumors in their patients.”

Lapointe added that as they continue to screen more samples, they

may find even more subtypes to further characterize and better

predict the course of prostate cancer.

This research was made possible through National Institutes of

Health and National Cancer Institute sponsorship, part of a larger

research grant of biochemistry professor and Howard Hughes Medical

Institute investigator Patrick Brown, MD, PhD. Brown developed

microarrays at Stanford and collaborated on the study.

Seven other Stanford investigators from the departments of

pathology, urology, health research and policy, statistics and

genetics contributed to this project. This study was part of an

international collaboration and included investigators from Johns

Hopkins University, Louisiana State University and the Karolinska

Institute in Sweden.

|

Researcher

challenges value of widely used prostate cancer diagnostic tool

(2/13/02)

Controversial

faculty finding gets nationwide airing (10/9/02)

|