|

Researcher

wishes estrogen study went a year longer

By SUSAN IPAKTCHIAN

Publishing the results of a nearly seven-year Women's Health

Initiative study dealing with estrogen therapy is bittersweet for

Marcia Stefanick, PhD, professor (research) of medicine at the

Stanford Prevention Research Center and chair of the WHI national

steering committee.

While Stefanick is pleased that the results provide clear evidence

that initiating unopposed estrogen therapy for women in their 60s

and 70s is not beneficial, she's disappointed that a decision to

end the study a year early means that answers aren't as precise for

women in their 50s.

"I think it puts exactly the same questions back on the table that

were there when we started the trial for women in their 50s,"

Stefanick said. "We probably could have answered them if we had

been given the full eight years."

The estrogen therapy tria l-- involving nearly 11,000 women

nationally between the ages of 50 and 79 who had undergone a

hysterectomy -- was halted at the end of February because of

concerns that estrogen increased the risk of stroke while offering

no protection against heart disease. The initial study results are

published in today's issue of the Journal of the American

Medical Association.

Graph: Courtesy of Marcia

Stefanick

Although the primary purpose of hormone therapy is to help relieve

the effects of menopause, observational studies and other evidence

over the years have suggested that hormones might prevent heart

disease and bolster the overall health of older women. The WHI

study wanted to answer those questions definitively.

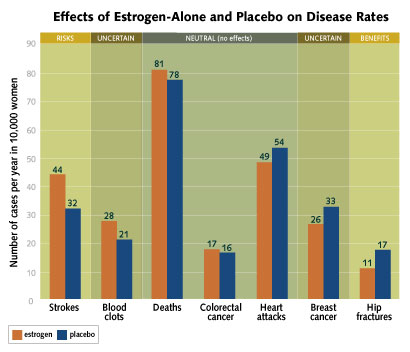

Overall, the results show that the estrogen used in the study,

known as conjugated equine estrogen, doesn't appear to have any

effect on the risk of heart attacks, colorectal cancer or deaths.

The study showed a 39 percent increase in the risk of stroke, going

from 32 strokes per 10,000 women among those taking a placebo to 44

strokes per 10,000 women among those on estrogen. The one clear

benefit of estrogen was in a decreased risk of hip fracture. Two

areas in which estrogen's effect is uncertain are breast cancer and

blood clots. Although fewer women on estrogen developed breast

cancer, researchers said the result was not statistically

significant.

But when the results are broken down by age group, Stefanick said,

the findings aren't as clear-cut for women in their 50s. For them,

estrogen appears to reduce the risk of heart disease and the

overall picture suggests benefit.

"For women in their 60s and 70s, I think the message is pretty

clear that initiating hormones is not beneficial for preventing

heart disease or for their overall health," Stefanick said. "But

for women in their 50s who have had a hysterectomy, this study does

suggest some benefit. We would have had better information if we

could have continued the trial for another year."

The decision to halt the trial was made by the National Institutes

of Health. Although none of the previously established boundaries

for stopping the study was crossed, the NIH felt that the increased

risk of stroke was not acceptable in healthy women in the absence

of any benefit to heart disease. While Stefanick acknowledged that

concern, she was unclear as to whether it outweighed the benefit of

continuing the trial for another year to give women more precise

answers about the balance of risks and benefits of estrogen.

"We're in the unfortunate position of having stopped the trial

because of the risk of stroke, which occurred primarily in women in

their 60s and 70s," she said. "The study came up short for women in

their 50s."

Stefanick said the early end of the trial also makes it difficult

to know how long women can safely continue taking estrogen. In the

findings related to heart disease, the results showed that women on

estrogen had more heart attacks in the initial years but Stefanick

said this effect diminished over time in a significant way.

"While we would encourage older women not to initiate hormone use,

there's nothing from this study to suggest that they should stop

taking it if they've already been on it for up to seven years," she

said.

For women in their 50s who are contemplating whether to initiate

estrogen, Stefanick said they should discuss their questions with

their physicians. "There's certainly good evidence that it's not

harmful for women in their 50s who have had a hysterectomy and

would only take estrogen for at least seven years."

The message for all women and their physicians is that hormone

therapy should be used for relief of hot flashes and other symptoms

related to menopause and not as a method of preventing disease,

Stefanick said. The Food and Drug Administration recommends that

women use the lowest hormone dose needed to achieve treatment goals

and limit the duration of the therapy.

Stefanick said she and the other WHI investigators will continue

analyzing the data in the coming months and will publish more

detailed results in the fall. The study also has received funding

to continue tracking clinical outcomes in the women through

2010.

WHI was launched in 1991 to examine the most common causes of

death, disability and impaired quality of life in postmenopausal

women. The 15-year, multimillion-dollar effort involves more than

161,000 women nationwide.

In addition to the study of estrogen and an earlier study of the

combination of estrogen and progestin, the study has arms examining

the role of a low-fat diet in reducing breast and colon cancer; the

role of calcium and vitamin D in fracture prevention; and an

observational study to identify disease predictors. Those arms are

continuing.

In 2002, the arm dealing with the estrogen-progestin combination

was halted because of evidence that the participants experienced a

greater risk of breast cancer, heart attack, stroke and blood

clots.

|