Medieval songs reflect humor in amorous courtships, Stanford scholar finds

Through a new translation of medieval songs, Stanford German studies Professor Kathryn Starkey reveals an unconventional take on romance.

Medieval courtship brings to mind images of chivalrous knights worshipping fair damsels, expressing their love for their ladies in refined and poetic language.

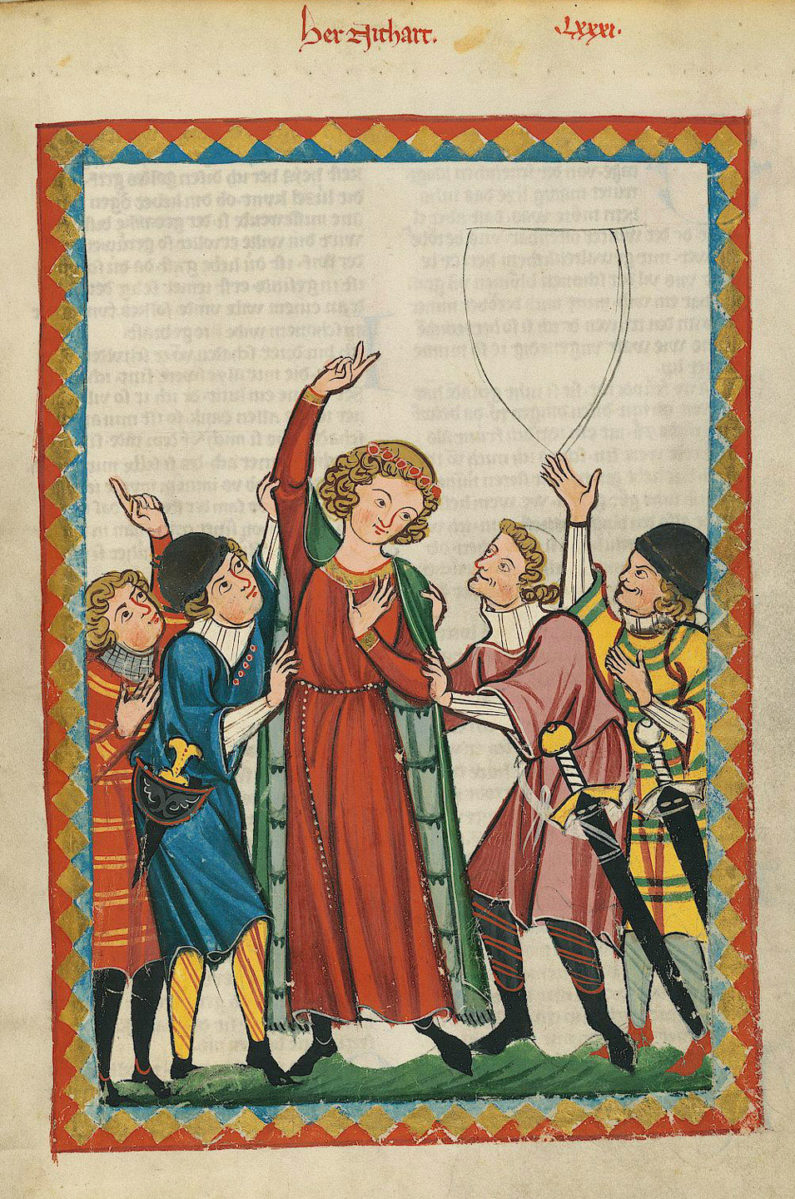

Illustration is taken from the Codex Manesse, a prime source of medieval poetry in German and particularly of courtly love poems. Stanford Professor Kathryn Starkey explores the works of one such poet, Neidhart von Reuental, in a new book. (Image credit: Wikimedia Commons)

But courtship did not play out this way for all medieval knights. Neidhart von Reuental (1190-1237), a medieval German poet, composed songs about a fictional knight whose amorous pursuits were often obstructed by local peasants.

In a forthcoming book entitled Neidhart: Selected Songs from the Riedegg Manuscript, Kathryn Starkey, professor of German Studies at Stanford University, and Edith Wenzel, professor emerita of German literature at the University of Aachen (Germany), offer the first collection of Neidhart’s songs translated into English.

During the Middle Ages, Neidhart was considered one of the Minnesänger (literally “love singers”), or German poets who, like the French troubadours, wrote songs and poems about courtly love. But drenched in slapstick humor and sexual innuendos, Neidhart’s lyrics often defied the high style of his fellow poets.

“Neidhart was the most prolific poet of his time,” Starkey said. “But he’s not well known because he has not been translated into English. And so it was important for me to make his work accessible because he’s such a canonical figure and he’s such an interesting figure.”

Although Neidhart did not criticize elite culture, he mocked it by relocating courtly motifs into the realm of ridiculous rustics. “Nothing is sacred for Neidhart,” Starkey said.

“Neidhart is so clever,” she said. “What is unique about him is his humor, parody, and the way that he takes conventions and turns them on their head and surprises us constantly by twisting expectations.”

Knights and free-thinking maidens

Many of Neidhart’s songs take place in a village where the poet imagines an unwanted encounter with local peasants. They bar access to his beloved lady. These fictive peasants also try to imitate courtiers, parading around in fine clothing or carrying swords as would noblemen. Yet they ultimately contaminate courtliness with their unruly antics, as one of the poems suggests:

Look at Engelwan [a peasant], how high he carries his head.

Whenever he struts at the dance with his sword drawn,

he is not lacking in

Flemish courtliness,

his father Batze has little to do with that.

Now, his son is a vain fool with his rough cap.

I compare his puffing himself up to a fat pigeon

perched with a full gullet on a grain box.

So why was Neidhart, by all accounts of knightly lineage, so obsessed with, and seemingly threatened by, peasants?

“That’s the million-dollar question,” Starkey said.

There is actually no historical evidence that suggests that knights of this era had this level of contact with the lower classes. For recent scholars, Neidhart’s predicaments might point to tensions between the lesser nobility and peasants.

“Neidhart was composing in upper Austria,” Starkey said, “where there were many ministerial families.”

Though noble, these families served an overlord, and were therefore not entirely free. According to Starkey, “it was important for them to continually affirm their nobility and their difference from the peasants who were also un-free, but of an entirely different social estate.”

Moreover, there were laws concerning class-specific clothing. For example, some laws permitted peasants to wear only gray, blue or black – the cheapest colors to produce.

“So we know that this was a contemporary issue in Neidhart’s period,” she said.

In his poems, Neidhart often depicts himself falling in love with a beautiful peasant woman. Perhaps this was part of a medieval male fantasy to dominate women or showcase women as sexually available, rather than virginal and unattainable.

However, Neidhart’s women could appear empowered.

“In terms of gender,” Starkey said, “he does create a space for women to express their sexual desire.”

With this, Neidhart again departs from conventions of courtly love. While traditional medieval love poems feature a male voice who objectifies his lady, some of his poems imagine maidens talking with one another about whom among the knights they like, why and what to do about it – what Starkey considers “an acknowledgement of female sexuality.”

Translation and teaching

Starkey said she believes that her translations will affect how medieval German literature is taught, given that “Neidhart’s songs are so unusual that if they were translated they could be taught in a whole host of courses that deal with medieval culture, sexuality and humor.”

Her translation has also spawned a digital humanities collaboration.

“I’ve just started a project called ‘The Medieval Sourcebook,’” Starkey said, adding, “Together with my graduate students, we are creating online parallel English translations of medieval texts to be used by teachers and students.”

The Medieval Sourcebook reflects some of the challenges Starkey faced when translating Neidhart into English. Some of the terms he uses – chiefly colloquialisms and idiomatic expressions – hinder translation, since they appear solely in Neidhart’s works.

“We don’t know exactly what some of his expressions mean. You have to look at the context and think about what the possibilities are,” Starkey said.

Reflecting on the value of her contribution, Starkey said she hopes that her translations “will get students thinking about their own language, about foreign language and about the relationship between them, as well as the tensions that arise when you try to translate a cultural document in one language into a cultural document in another.”

After working on Neidhart and with her students, Starkey realized that “we as scholars think we know texts. But when you translate them, you get a completely different understanding of them.”