How waste from the mining industry has perpetuated apartheid-like policies in South Africa

Through studying the residues of South Africa’s mining industry – a core infrastructure of the apartheid regime – Stanford historian Gabrielle Hecht shows how its deleterious effects continue.

While apartheid – South Africa’s brutal racial segregation laws of the 20th century – officially came to an end in the early 1990s, its harmful effects persist today, says Stanford historian Gabrielle Hecht in her new book, Residual Governance: How South Africa Foretells Planetary Futures (Duke University Press, 2023).

“You can see apartheid from space,” Hecht bluntly states in the book’s opening chapter.

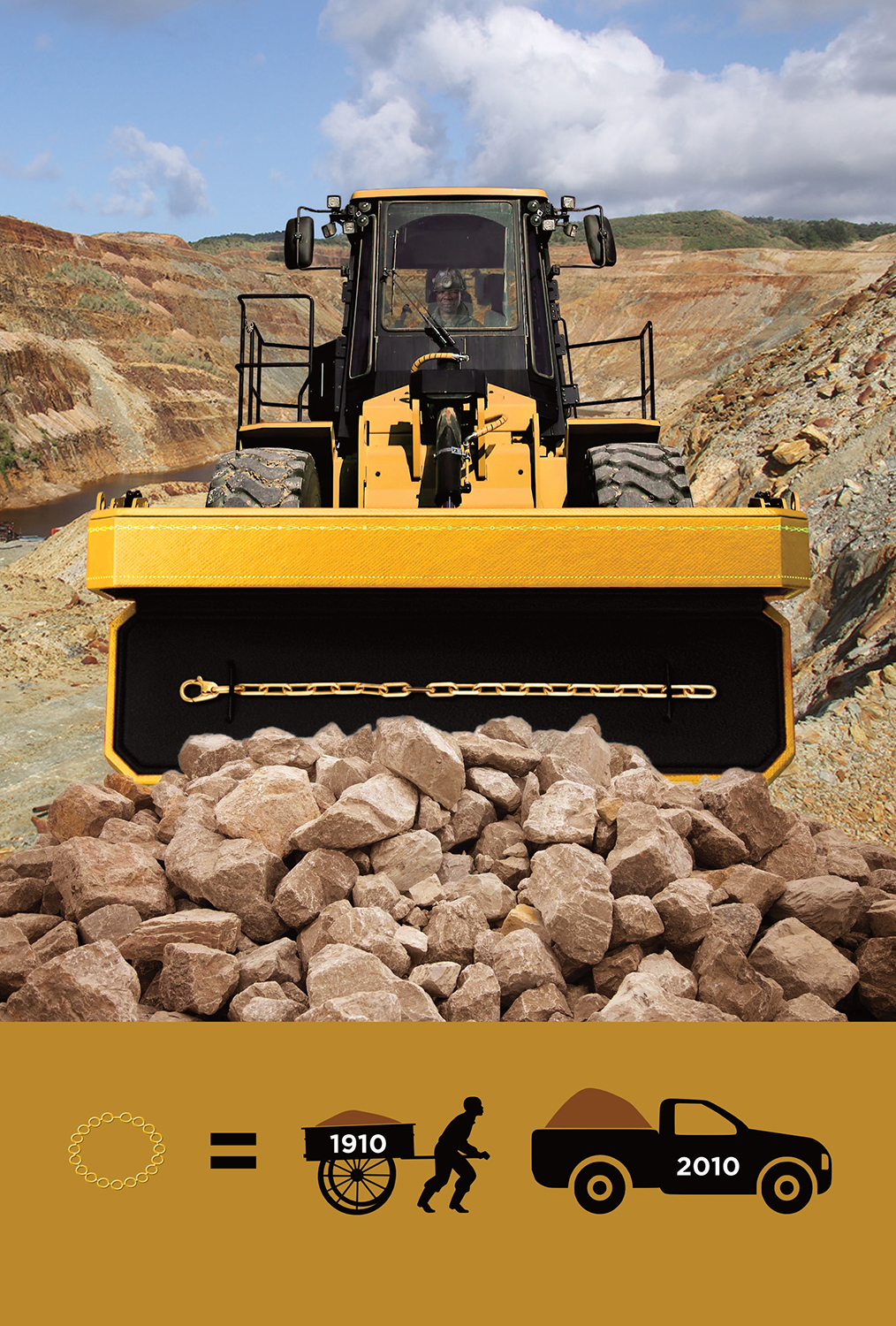

The amount of waste mining generates is immense, almost incomprehensibly so: It takes one ton of discarded rock to produce just one 14-karat gold chain. The massive piles of mining discards – known as tailings – can be seen on satellite imagery.

For the past two decades, Hecht has traveled throughout the Witwatersrand plateau, also known as the Rand, a 100-kilometer expanse where one-third of Earth’s gold has come from.

Amid the tailing piles pulse the activities of most impoverished, Black South Africans and migrants trying to salvage their own lives out of the scraps: Some dangerously go deep into abandoned mine shafts in search of what little gold remains, if any. Others use the toxic leftover debris to make bricks, sold to people tired of waiting on the government’s 30-year-old promise for universal housing, to cobble together their own makeshift shelter.

When Hecht met with one man running one of these operations, he gestured at her colleague and asked, “Does she know that all the quartzite around here is radioactive?”

During South Africa’s winter months, winds blow toxic dust off these tailing piles, sending residues downwind, where – no coincidence – Black residents reside and breathe in these noxious particles. White communities are found upwind – further topographical markings of the racist policies that continue to shape the country today.

This is another reason, Hecht says, apartheid can be seen from space.

Persistent problems

As Hecht shows, the same people apartheid oppressed and profited from bear the costs of the nation’s mining debris: poor, Black South Africans living on the economic margins.

These people continue to live, breathe, and ingest hazardous waste with devastating health consequences, including fatal cancers and genetic defects.

“There is no such thing as ‘out of sight, out of mind,’” said Hecht in an interview with Stanford Report. “Waste does not magically leave the planet. It’s active, not passive. Waste doesn’t just sit there and do nothing. It mutates, it seeps, and does all kinds of horrible things.”

Throughout the book, which is freely available to read through Open Access, Hecht mixes anecdotes and personal stories with historical analysis, data, and other evidence and reports gathered by government agencies and nonprofit organizations to show how waste continues to perpetuate the racial disparities of the apartheid regime. Interspersed are dozens of images, including visual montages by the graphic artist Chaz Maviyane-Davies and sepia photography by Potšišo Phasha, that depict the multitude of issues resulting from the toxic debris the mining industry has left behind.

Each chapter opens with a montage designed by the Zimbabwean visual artist Chaz Maviyane-Davies. “Think of them as visual epigraphs, ways of foreshadowing an aspect of the chapter they precede,” Hecht describes. (Image credit: courtesy Chaz Maviyane-Davies)

The massive tailing piles themselves pose problems, as they contain toxic materials such as mercury.

But there are other problems as well. For example, mining is a water-intensive practice, one that has drained the country’s aquifers over decades, leading to water scarcity. What water remains risks becoming toxic, too. As water rises through abandoned mines – there are 6,150 defunct operations in the country – it acidifies and absorbs poisonous heavy metals like arsenic and lead before eventually seeping its way into the local water supply and onto farmland.

Hecht cites one report of a school located 500 meters away from a tailing dam. The school planted a garden to help feed the food-insecure school children, only to discover that the vegetables that their garden yielded were high in arsenic, mercury, and lead.

A system of residual governance

Hecht also features the environmental activists, scientists, community leaders, journalists, urban planners, and artists who are responding to the problem Hecht has conceptualized as “residual governance”: A “deadly trifecta” defined by: “minimalist governance” that “uses simplification, ignorance, and delay as core tactics” and “treats people and places like waste.”

While there are some regulations in place, a system of residual governance makes it difficult to enforce compliance. It also requires expertise that has been weaponized by the mining companies, who use it as a delay tactic, demanding “more research” when it is readily apparent the damage their operations have caused to the local communities.

Tackling a pernicious problem is undoubtedly complex.

Some first steps toward solving them could involve building more water treatment plants and remediating old mines, but as Hecht points out, long-lasting, sustained change also requires structural shifts.

“For those who fight against it, the opposite of residual governance is not a souped-up technocratic machine,” Hecht writes in the book’s conclusion. “It’s the creation and maintenance of systems and infrastructures that not only recognize and respect their full personhood (their voices, their bodies, their aspirations), but that have mechanisms for sustaining that recognition and respect over time.”

The future of mining

While Hecht focuses on South Africa, mining continues across a world moving toward a sustainable future where minerals such as copper, nickel, lithium, and cobalt are essential to a low-carbon and fuel-efficient transition. As a Guggenheim fellow this year, Hecht’s research now focuses on the wastes of extracting materials for green technologies.

Hecht hopes that the questions residual governance raises will also be included in future discussions about mining. As her historical analysis has shown, extraction also produces sociopolitical problems that all too often exacerbate existing vulnerabilities and racial inequalities.

Hecht also hopes that readers will become more aware as consumers.

“None of us are innocent here,” said Hecht. “This is connected to the rest of the world in these really disturbing ways.”

Subsidies from the School of Humanities and Sciences (H&S), the History Department, and the Freeman Spogli Institute for International Studies helped make the book available through Open Access. Hecht said it was particularly important that the material be accessible to people in South Africa and throughout the continent. In addition, all author proceeds from sales of the hard copy version of the book are going to South Africans mentioned in the book.

Hecht is the Stanton Foundation Professor in Nuclear Security, a professor of history in H&S, and a senior fellow at the Freeman Spogli Institute.