Stanford professor of music unravels centuries-old authorship mystery

A technique developed by Jesse Rodin and his colleagues blends scientific rigor with historical and musical clues to resolve a 500-year-old puzzle over works believed to be written by the famous composer Josquin des Prez.

The 15th-century French composer and singer Josquin des Prez, or “Josquin,” as he is commonly known, achieved the Renaissance equivalent of rock star status. Despite his fame, many details of Josquin’s life and career are hazy, and a big mystery of early music is how many of the several hundred musical compositions attributed to Josquin were actually written by him, according to Stanford musicologist Jesse Rodin.

Rodin, associate professor of music in the School of Humanities and Sciences, recently evaluated the authorship of the 346 pieces of music attributed to Josquin (1450–1521) using an approach that blends scientific rigor with methods from the arts and humanities. As part of this massive undertaking, Rodin created the Josquin Research Project, a searchable, online database of music by Josquin and his contemporaries.

Rodin identified a “core group” of musical pieces attributed to Josquin by reliable sources before evaluating Josquin’s musical style. Using this core group as a reference, Rodin and his colleague Joshua Rifkin, a scholar and conductor at Boston University, assigned confidence levels to the authorship of the remaining musical works attributed to Josquin. Rodin summarized the project in the Early Music paper The Josquin Canon at 500 and Rodin’s work on Josquin was featured in The New Yorker.

“It’s all too easy to approach this or any other data set mechanically – to say that there are seven sources that put Josquin’s name on this piece, so it must be his,” Rodin said. “But what if those seven sources all depend on an unreliable ‘parent’ source and thus carry no independent authority?”

At the heart of the project “is the use of evidence, and how tricky it is in any discipline – humanities or sciences – to weigh evidence in a way that’s neither rigid nor blind to context, circumstance, and history,” he said.

Josquin’s mysterious life and career

Rodin has dedicated much of his career to the study of 15th-century music, particularly to the work of Josquin, who is widely regarded as the first modern master of multi-voice, polyphonic music.

In addition to leading the Josquin Research Project, Rodin directs Cut Circle, a vocal ensemble that performs music by Josquin and his contemporaries. As a scholar, Rodin has published widely in this field, including the book Josquin’s Rome (Oxford University Press, 2012).

It is hard to know what music Josquin wrote for several reasons, Rodin explained. First, Josquin’s compositions weren’t reliably labeled. Second, several composers imitated Josquin’s music. Lastly – and most importantly – Josquin became internationally famous just as printing was revolutionizing the circulation of music. Consequently, nearly two-thirds of the music bearing Josquin’s name entered circulation only after his death.

“Some misattributions seem to be the result of wishful thinking: Then as now, people wanted to believe he composed a given piece,” Rodin said.

‘What’s in a name?’

Many attempts have been made to bring clarity to Josquin’s compositions. The Dutch musicologist Albert Smijers was commissioned to edit Josquin’s works in the early 1900s – an effort that took decades to complete. Then, in the 1970s, an international team of scholars formed the New Josquin Edition committee: Over three decades (1986–2017), they published 30 volumes of music attributed to Josquin.

But just as the project was getting going, Rifkin called the underlying methodology into question, suggesting that the committee had failed to adopt sufficiently rigorous criteria for assessing the reliability of the sources. Rifkin proposed that scholars should consider works by Josquin “guilty until proven innocent” – that is, not by Josquin until proven otherwise.

At the time, Rifkin’s proposal was considered extreme. For centuries, people writing about early music have assumed Josquin composed most of the pieces attributed to him. Also, the timing wasn’t ideal – the New Josquin Edition was about to publish its first volume.

“Understandably, some scholars and music-lovers feel robbed when a favorite piece is dropped from the Josquin canon,” Rodin said. “When the authorship of a beloved piece was called into question, the musical community would reel – as if the music could no longer be good if it was no longer Josquin’s.”

The Josquin Research Project

While editing a volume of L’homme armé masses for the New Josquin Edition (2014), Rodin began working with Rifkin to explore how a guilty-until-proven-innocent approach might be applied to Josquin’s music.

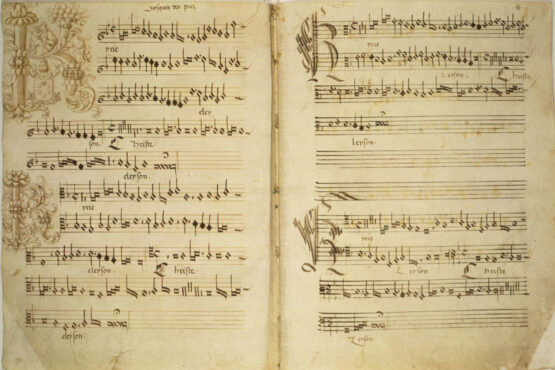

The Kyrie from the Missa de beata virgine by Josquin des Prez in the Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Ms. Cappella Sistina 45, folios 1v-2r. (Image credit: Wikimedia)

“Our aim isn’t to ignore the vast body of scholarship and popular knowledge about Josquin,” Rodin said, “We ask: ‘What does the most reliable evidence tell us? And how do we manage that evidence, and manage uncertainty, without letting untrustworthy information in the door or falling prey to wishful thinking or circular reasoning?’ ”

In 2010, Rodin created the Josquin Research Project in partnership with Craig Sapp, adjunct professor at Stanford’s Center for Computer Assisted Research in the Humanities. Putting new digital tools to use, they began refining our understanding of Josquin’s musical style, or as Rodin puts it, what “Josquin tends to do and not do” in his music, by analyzing pieces for which the source evidence alone makes Josquin’s authorship almost certain. This core group of 54 works was crucial because it served as a reference that helped the team recognize other music by Josquin.

The short sacred piece Domine, non secundum peccata is part of the core group. It was copied into a Sistine Chapel choir book around 1490 while Josquin was singing and composing music there. It is attributed to “Judocus de pratis,” the Latinized form of Josquin des Prez, on the first page of the Cappella Sistina 35 on folio 5v.

“If this scribe didn’t know what was Josquin, pretty much nobody did. So on the testimony of one manuscript, we can feel very safe about the work’s authorship,” Rodin wrote in Early Music.

Taking a comparative approach to source- and style-based evidence, Rodin and Rifkin assigned the remaining 292 pieces not in the core group to one of three categories: provisionally attributable (49 works); “problematic, ranging from ‘fat chance’ to ‘could be’ – but are there really good reasons to believe it is?” (35 works); and “the rest” (205, plus 3 lost compositions). In all, Rodin and Rifkin believe Josquin composed about 103 of the 346 works attributed to him – as compared to 143 compositions deemed secure by the New Josquin Edition.

Days before Aug. 27, 2021 – the 500th anniversary of Josquin’s death – the team finished tracking down, transcribing, and uploading to the Josquin Research Project’s fully searchable, online collection every surviving note attributed to Josquin. Rodin marked the anniversary and the project’s completion with a series of performances by Cut Circle that were recorded in Florence and Arezzo, Italy, cities close to where Josquin worked.

Rodin and Sapp have been developing new analytical tools and expanding the Josquin Research Project database to include music by other composers.

Rodin’s forthcoming monograph explores issues of musical form in pieces by Josquin and his contemporaries. He is also co-editing a book, provisionally titled Josquin: A New Approach, that features essays by prominent scholars writing about Josquin for the first time. “It’s exciting to finally be in a position to probe Josquin’s works and compare his style to music by other composers without worrying the findings will be clouded by problems of attribution,” Rodin said.

“Josquin’s compositions changed the course of music history in ways that continue to resonate today,” he added. “His music is not played on American radio with the same frequency as that of Liszt or Lizzo, but that doesn’t mean it doesn’t matter.”

This research was supported by funding from the Guggenheim Foundation, the American Council of Learned Societies, and Stanford University, with in-kind support from the Center for Computer Assisted Research in the Humanities (CCARH).