Stanford researchers develop an intervention that cuts recidivism among children reentering school from the justice system

New data show that a one-page letter asking a teacher to support a youth as they navigate the difficult transition from juvenile detention back to school can reduce the likelihood that the student re-offends.

For a child leaving juvenile detention, building a relationship with a teacher who believes in them can make all the difference. A new Stanford-led study suggests that a personalized one-page letter can go a long way toward helping forge that relationship – and reduce the likelihood that the student will re-offend.

Go to the web site to view the video.

Researchers found that this letter, which articulated the child’s aspirations and asked for their teacher’s support, reduced recidivism to juvenile detention through the next semester from 69 percent to 29 percent in a small initial sample, published Oct. 4 in Psychological Science.

“Our goal was to create an experience where children could reflect on their positive goals and values, what they wanted to do in school and who they wanted to be, and then to identify an adult in school who they thought could help,” said Stanford psychologist Greg Walton, lead author of the study. “Then we gave kids a platform to elevate their voices directly to that person, introducing themselves in a positive way. We hoped that would help orient both the student and their chosen teacher toward each other, as people who could come together with trust and respect to do the hard work of reentry.”

The researchers also include Jennifer Eberhardt, a professor of psychology in Stanford’s School of Humanities and Sciences, and UC Berkeley’s Jason Okonofua, who studied under Walton and Eberhardt during his doctoral studies at Stanford. The team worked closely with the Oakland Unified School District (OUSD) in partnership with the Alameda County Juvenile Justice Center (JJC), as well as community after-school groups and programs across Oakland, California, to better understand the challenges young people leaving juvenile detention face and how teachers and students can work together to make the transition back to school successful.

Community-rooted research

The intervention the research team developed drew from a rigorous, 15-month long pilot project with community partners in Oakland, including OUSD and the JJC.

Oakland, a diverse and vibrant city east of San Francisco, has also faced challenges with crime and gang violence. Youth who get caught in criminal activity end up at JJC, a detention facility for minors.

Many of the youth who are detained in Oakland are also Black. On average 73.5 percent of all juvenile arrests by the Oakland Police Department are children of color, even though they represent only one-third of Oakland’s youth population, according to one report co-authored by the ACLU of Northern California.

The researchers spoke at length with some of these children. They learned about the challenges they faced upon release from JJC and heard stories about instability at home and in their neighborhoods, being behind in school and the various traumas they endured – several children spoke of having seen friends get shot before the age of 12.

Another challenge students described involved the severe stigma they faced as people who had been detained in the justice system. As prior research has shown, youth with experience in the justice system can be seen as a lost cause, as out-of-control or as troublemakers – particularly if that child is a person of color. These biases, even if unconscious, can give rise to mistrust and escalate conflict in the classroom that ultimately undermines students’ learning experience and pushes them deeper into the criminal justice system.

Reorienting the student-teacher relationship

Combining on-the-ground insights with the researchers’ previous scholarship – including Eberhardt’s extensive research on bias, Walton’s work on how improving a student’s sense of social belonging at school can reduce racial disparities in discipline citations, as well as his research with Okonofua showing that increasing teachers’ empathy for misbehaving students can reduce suspension rates – the team developed an intervention and tested it with 47 youth who had been detained at the JJC and were returning to middle or high school in the OUSD.

Instead of trying to confront or overturn stereotypes – common approaches to problems of bias – the researchers took an approach that aimed to “sideline” bias.

“Bias can be activated or deactivated in the situation,” Eberhardt explained. “We know the situational triggers for bias, and if we have that in mind, then we can think about bias as not just something associated with how a person thinks but related to the situation they are in.”

The researchers decided to create an environment that would make it hard to trigger people’s biases and stereotypes. So they created a situation that invited teachers and students to become their best selves for each other.

“Teachers want to have positive relationships with kids. They want to be a person a kid can rely on, especially a kid facing a difficult situation, and help that kid succeed,” said Walton. “The goal of this approach is to evoke that positive self, to evoke that teacher self that is caring and supportive and to not let bias be what controls behavior.”

Testing the intervention

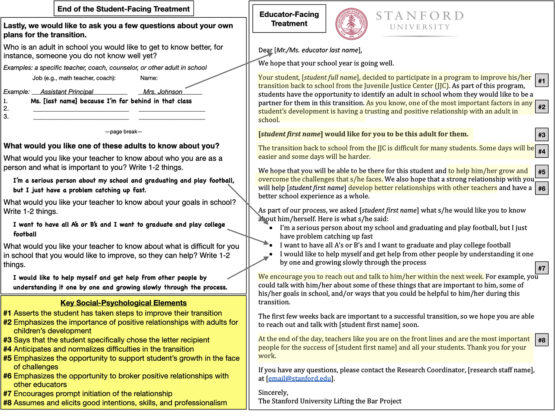

The intervention began shortly after each child was released from JJC in a one-on-one meeting at the child’s school between them and a member of the research team.

The team member opened the session by acknowledging that the transition back to school is hard. They shared how they had spoken with other students who had gone through this transition but wanted to learn more from the child directly so they could help other children in the future. They then shared two things that other students in similar situations had found helpful: First, identifying their personal goals and values. And second, establishing relationships with adults at their school who could help them make progress toward these goals.

The researcher then gave the student a list of values, called “ideas from other students.” Included were statements such as “Make my parents proud of me”; “Be a good role model for my younger brother or sister”; “Learn skills that could help me get a good job.” The student chose the values that mattered to them most and said why.

Next, students heard stories from four other youth drawn from the pilot process. Through these stories, students learned about challenges older students had faced, and how relationships with adults at their school had helped them. As one story said, “The world seems difficult sometimes, but things seem a lot more doable knowing there are people who have your back. It helped me feel more in control.”

The student also learned that building rapport with adults was not always easy, but that with persistence, a relationship could be established.

The student was then invited to share their own story and ideas about how they could develop relationships with adults that could be important for them – a psychological strategy Walton has called “saying is believing.” His research has found that a powerful way to help people internalize a message is to ask them to describe it in their own words.

Finally, the researchers asked the child to name a teacher at their school who they thought could help them. They were asked to describe what they would like this person to know about them, including who they are as an individual and what is important to them, as well as the challenges they faced at school that the teacher could help with.

The researchers then delivered a personalized, one-page letter to that teacher.

The letter included the information the student provided, including the child’s hopes and dreams. As one letter read: “I’m a serious person about my school and graduating and play [sic] football, but I just have problem [sic] catching up fast.”

The letter also emphasized the importance teachers play in a child’s life, “As you know, one of the most important factors in any student’s development is having a trusting and positive relationship with an adult in school.” And it emphasized that the student had chosen the adult personally, “[Student name] would like for you to be this adult for them.”

The research team closed the note by thanking the teacher for their work and acknowledging the role they play in a child’s success.

“While educators have worked in a system that has failed youth, that has failed them and sometimes is seen in our society as a failing system, nobody signs up to go to work every day and fail,” said Hattie Tate, an administrator/coordinator for the OUSD in partnership with the JJC and a co-author on the study.

The main goal of the letter, Tate explained, is to shift the teacher’s pattern of thinking. “A key part of the work that we do with this intervention is changing the mindset, the fixed thought of adults about youth that get involved in the justice system,” she said. “As educators, this intervention gives us a lot of opportunities to shift the culture and the climate of schools by having adults believe in at least one student’s success.”

The results of this simple letter were stunning. In the control group where a letter was not presented to the teacher, two out of three students – 69 percent – recidivated. But for students whose teacher received the letter, it was less than one in three: 29 percent.

The researchers also ran a test group where the one-on-one session was administered but no letter was delivered (students were always told the researchers “might” be able to deliver the letter). In this group, 64 percent of students recidivated, indicating that the letter was a key factor in improving children’s outcomes.

What made the intervention so successful was the partnership it inspired between student and teacher, said Eberhardt.

“The letter that the teacher received allowed the student to tell their story to that teacher and tell it in a way that the teacher was committed to their success,” she said. “The teacher knew that this student identified them as the person they wanted to partner with. That mattered, because it’s not researchers, it’s not administrators, it’s the student identifying the person that they think would be best for them to partner with on this journey back to school.”

Next steps

With further support from the Stanford Impact Labs, a new initiative that connects Stanford faculty studying social problems with community partners to co-create solutions, the researchers will continue to work with Oakland and expand their study to the city of San Francisco and Sacramento County to evaluate the effectiveness of this approach and how districts and counties can implement it in a sustainable, policy-relevant way.

As the researchers note in the paper, the stakes could not be higher.

Tate recounted an exchange she had with an adult inmate who was participating in a literary program at a detention center in Alameda County. “A 50-year-old inmate said, ‘I shouldn’t have had to wait until I was 50 to enter an environment where somebody tells me, you can learn to read. You can do math,’ ” she recalled. “Taking time to create this intervention and connect teachers and students is really important, especially for young, troubled students.”

In addition to Gregory Walton, Jason Okonofua, Hattie Tate and Jennifer Eberhardt, co-authors include Kathleen Remington Cunningham, who received her PhD from Stanford Graduate School of Education and is now research director at the Minnesota Justice Research Center, and Daniel Hurst. Andres Pinedo at the University of Michigan, Elizabeth Weitz at the University of Hawaii and Juan P. Ospina at Ohio State University also contributed.

Support for the study came from Character Lab, a nonprofit organization that advances scientific insights to help kids thrive.