Stanford students study the stories behind medical breakthroughs

In a graduate seminar taught by Stanford medical anthropologist S. Lochlann Jain, students examined how previous epidemics – such as yellow fever, smallpox, polio and AIDS – can illuminate the social dynamics and politics of the era.

As the world races to find a treatment for COVID-19, a group of Stanford graduate students have reflected on the extraordinary – and often difficult – history of disease, vaccination and prevention.

Go to the web site to view the video.

In a graduate seminar, The History of Vaccines, taught by Stanford medical anthropologist S. Lochlann Jain, students learned that behind stories of scientific success is a complicated and complex past that, when closely examined, can reveal the social dynamics of the era.

“This history of vaccines is an incredibly interesting history of social relationships, colonial relationships, global relationships, and relationships between animals and humans,” said Jain, a professor of anthropology in the School of Humanities and Sciences.

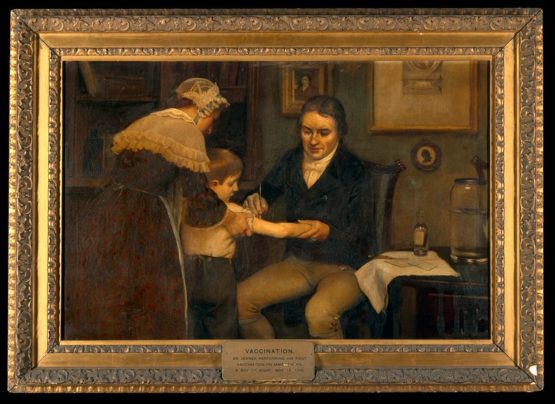

For example, when British physician Edward Jenner developed the smallpox vaccine in the late 18th century, he used his gardener’s 8-year-old child as one of his test subjects – an action that demonstrates both the loose ethical standards and social hierarchies of Georgian England. Jain also pointed out that Jenner’s idea for inoculation came from countryside folklore that dairymaids’ exposure to cowpox made them immune to smallpox.

“Although Jenner is known as the father of vaccinations, the idea didn’t come from nowhere. He built on social knowledge of the time,” said Jain.

Beyond the breakthrough

Jain also tried to impress upon her students that the journey from a scientific discovery to a medical treatment can be arduous.

Edward Jenner performing his first vaccination, on James Phipps, a boy of 8. May 14, 1796. (Image credit: Wellcome Collection. Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0))

While Jenner discovered a preventive measure against smallpox, it took over 150 years for his method to be administered in a way that was safe to vaccine recipients. For example, early experiments exposed test subjects to the virus to make sure the vaccine worked, which sometimes led to infection and even death from the very illness one was being inoculated against. In other instances, early doses of the vaccine were sometimes contaminated with other harmful agents, such as the bacterium that causes syphilis.

“This history raises a host of questions about how we think about what is effective,” said Elliott M. Reichardt, a PhD student in anthropology, who took the class. “It challenges this history that we have of Edward Jenner and that the development of the smallpox vaccine was just perfect. No – it was quite dangerous for a lot of people.”

Reichardt said he was also surprised to learn about other dangers scientists encountered as they developed vaccines for other diseases, including the polio vaccine. For example, throughout the 1940s and 1950s, researchers in the U.S. relied on monkey cell lines in vaccine production. However, due to inadequate sterilization procedures, millions of Americans were inadvertently infected with an animal virus, simian virus 40.

“What these examples reveal is the iterative nature of engineering and medical research,” said Reichardt. “It also illustrates how this complex past is at times neglected in explaining the origins of contemporary vaccinology.”

Students also learned that these origin stories can illuminate the interplay between science and global politics.

For example, during development of the polio vaccine in the 1950s, scientists and government officials put aside Cold War politics of the era in a global effort to eradicate the disease. Students studied the case of communist Hungary, which even during the midst of civilian uprisings lifted the Iron Curtain to allow scientific collaborations with the West, enabling the import of both the polio vaccine and iron lungs, tank respirators used to support breathing in polio patients.

“If there is the right disease, avenues for collaboration can open up politically that otherwise might seem impossible,” said Reichardt.

Relaying between past, present

As the class learned about the global challenges of combating smallpox and other diseases like yellow fever, polio, HIV/AIDS, Ebola and Zika, they had to reckon with a pandemic of their own: the novel coronavirus.

“It was reassuring to know society is not going to collapse and we will be fine. Humans are resilient and we’re going to get through this.”

—Elliott M. Reichardt

PhD Student in Anthropology

With their own world upended by uncertainty of a new virus, stories from previous outbreaks felt all too familiar – particularly how people grappled with an illness they knew little about. For example, during the polio outbreak in the 1950s, all that people knew about the disease was that children were particularly vulnerable. Out of fear, some parents forbade their children from going outdoors.

“We could understand it from a very personal, urgent kind of way,” said Jain, who is currently studying how HIV/AIDS first emerged in New York and San Francisco when little was known about the disease – other than that it was fatal.

“Having to personally weigh our own risks amid uncertainty gave us a new insight into how people may have made decisions about sociality before they understood what they were dealing with, in the polio epidemic or in the HIV epidemic,” Jain said. “The pandemic has been particularly difficult for people in non-normative families, such as young people and queer people. This has provided insight into the early days of HIV.”

As Reichardt adjusted to sheltering-in-place, he said he was consoled by the knowledge that this was by no means the first occasion in history when people had to confine themselves to prevent contagion.

“Humans have been isolating themselves for extended periods of time for very long periods of time,” said Reichardt, observing that Italians in the 14th century quarantined themselves as a way to thwart the bubonic plague. “It was reassuring to know society is not going to collapse and we will be fine. Humans are resilient and we’re going to get through this.”