Stanford grad students develop award-winning app that streamlines U.S. Air Force training

A suite of mobile learning tools created at Stanford, which recently won the top prize of $30,000 at a national security innovation competition, is capturing the attention of U.S. military officials.

An interdisciplinary team of Stanford graduate students is developing an app to improve training for U.S. military personnel.

The technology – originally created to help sports teams train athletes more quickly and efficiently – is receiving rave reviews from military leaders and recently garnered the top prize at the U.S. Department of Defense-sponsored Hacking4Defense competition in San Francisco.

Andrew Powell, MBA/MA ’20, said his team’s approach addresses a persistent problem facing the U.S. armed forces, particularly the Air Force.

Phil Stiefel, JD/MBA ’21, at Beale Air Force Base near Sacramento. (Image credit: Courtesy Phil Stiefel)

“Pilots often lacked accessible, effective tools for staying up-to-date on the mechanical and engineering details of their aircraft or for learning new emerging topics,” he said. “Things like an updated emergency procedure plan that evolves in light of what people learn from a mishap.”

During spring quarter, Powell and fellow grad students Phil Stiefel, JD/MBA ’21; Sasha Seymore, JD/MBA ’20; and Samuel Lisbonne, MS ’20; teamed up to solve the problem. They enrolled in MS&E 297: Hacking4Defense, a course in which students invent new technologies that tackle complex problems critical to the U.S. Department of Defense or the intelligence community.

Adapting sports tech

Before coming to Stanford, Powell and Seymore developed a platform to help football players and other athletes learn playbooks and game plans in an accelerated and more effective way. Learn to Win is a hit with college football programs.

At Stanford, Navy reservists Seymore and Stiefel ruminated on the limitations they experienced during their military training. That’s when it hit them.

“There was a flash-of-inspiration kind of moment when we realized we could use this platform to improve the accessibility, adaptability and functionality of Department of Defense trainings,” Stiefel said.

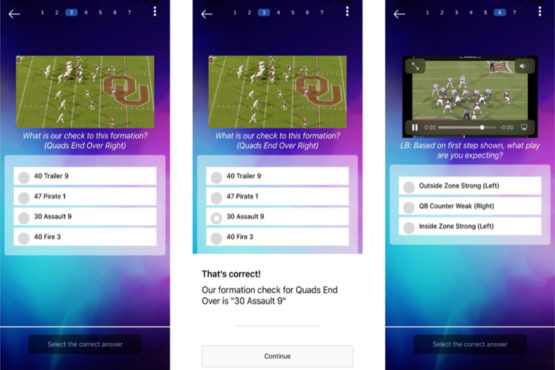

The mobile interface for Learn to Win, which was adapted to meet Air Force training needs. (Image credit: Courtesy Phil Stiefel)

In the Hacking4Defense course, the students began adapting Learn to Win for military instruction. However, the first few weeks proved to be challenging.

“We had no real direction for the first five weeks, and the course is structured that way on purpose to weed out any preconceived notions about solutions that participants have,” Stiefel said.

Halfway through the quarter, Steve Blank, one of the course instructors, encouraged the students to leave the classroom and talk to those who would be affected by their work.

So they visited Beale Air Force Base near Sacramento and Tinker Air Force Base in Oklahoma to interview military commanders. They learned that USAF training methods had gone unchanged for decades. Antiquated computer-based training programs weren’t compatible with the iOS or Windows and were accessible only off-base. The scores from computer-based trainings were recorded by hand and stored in three-ring binders. Aircraft technical manuals were often thousands of pages long. What’s more, these analog training methods cost American taxpayers hundreds of millions of dollars a year and generate little discernable return on investment.

“One thing that became perfectly clear from the class is that the high-budget, computer-based trainings the taxpayer is buying are hated by pilots and not being used after the first stages of training,” Stiefel said.

The students modified Learn to Win to streamline the training process. They created an interface that’s functional and adaptable to each user, integrated audio and video, and made the app compatible with mobile phones and tablets. They also developed a process to track and measure analytics, such as who takes the trainings and how they perform. With this app, Air Force commanders could create new lessons in a matter of minutes and push relevant, engaging training materials to airmen’s mobile devices.

A winning application

Feedback from Air Force personnel was overwhelmingly positive.

“People loved it,” Stiefel said. “Everyone expressed a preference for our model; exactly nobody that we interviewed said they would prefer to keep the status quo.”

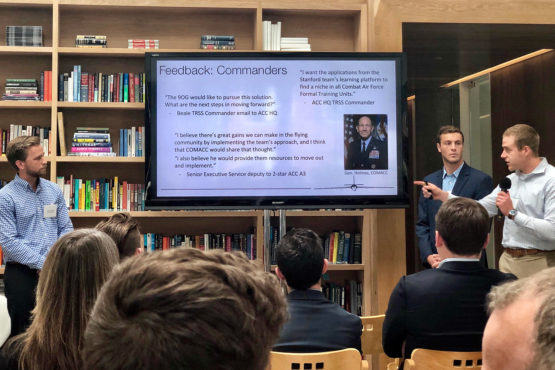

Stanford graduate students Andrew Powell, Samuel Lisbonne and Phil Stiefel present their app at the Hacking4Defense competition in San Francisco. (Image credit: Courtesy Phil Stiefel)

During spring quarter, Powell, Stiefel, Seymore and Lisbonne submitted their idea to the Hacking4Defense national security innovation competition sponsored by the U.S. Department of Defense. They beat out more than 200 teams from around the country to make it to the final round, which took place in June at the Founder’s Fund in San Francisco. There, the students pitched the app to a panel of Silicon Valley venture capitalists before claiming the top prize of $30,000.

This summer, the students will continue developing the app and are optimistic about the platform’s prospects.

“I think if the Air Force adopts this, then civil aviation is the next obvious market,” Stiefel said. He and his teammates credit much of their success to the Hacking4 Defense course.

“This class is exactly why I came to Stanford,” Powell said. “It allows you to tackle real-world problems and is a testament to the unique opportunities on this campus.”