Stanford student discovers writing on pieces of ancient Egyptian mummy case

A Stanford sophomore found inscriptions on an ancient Egyptian mummy case as well as the name of the woman buried in it while researching pieces of the artifact.

When Ariela Algaze signed up for a spring 2018 course on museums, she didn’t expect to get wrapped up in the mystery of an ancient Egyptian mummy case that Jane Stanford herself purchased more than 100 years ago.

Ariela Algaze studies pieces of the ancient Egyptian mummy case as part of her spring 2018 class, “Museum Cultures: Material Representation in the Past and Present.” (Image credit: Christina Hodge)

“I was just excited to learn how to put an exhibit display together,” said Algaze, a Stanford art history sophomore. “But I became obsessed with finding out everything I could about this artifact.”

Algaze’s research led her to discover information that was not known by university scholars – including inscriptions on the coffin and the name of the mummified woman inside it.

“Being able to see and examine words written on a 2,000-year-old coffin was an exhilarating feeling,” Algaze said. “It’s like a voice calling out thousands of miles away.”

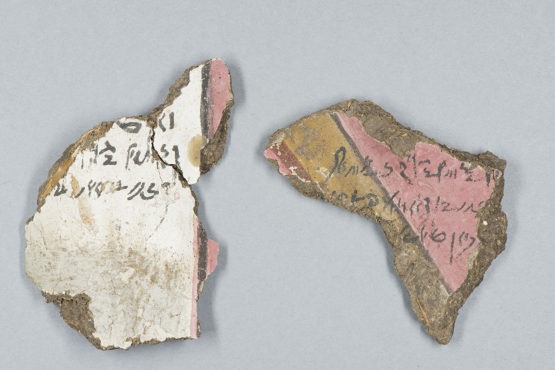

Algaze learned that the artifact contained writing after sifting through hundreds of its fragments, which have been stored in three boxes, unstudied for decades.

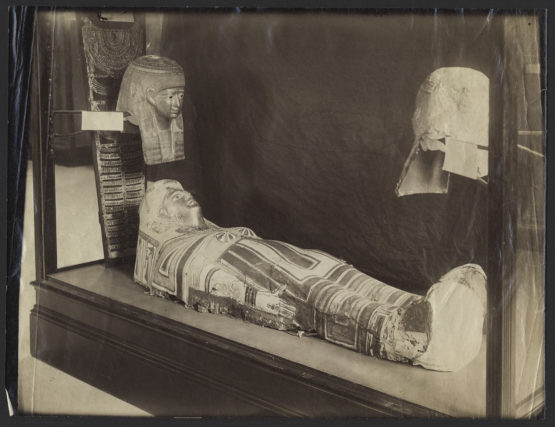

The mummy case, which Jane Stanford purchased in 1901, was once display at the Stanford Museum. But the 1906 earthquake shattered the coffin made up of fragile cartonnage, a type of ancient Egyptian material of either linen or papyrus covered in plaster, into hundreds of pieces.

The fragments went largely unexamined until Algaze took them out and studied each piece as part of Christina Hodge’s course, Museum Cultures: Material Representation in the Past and Present.

This historical photo shows the ancient Egyptian mummy case on display at the Stanford museum before the 1906 earthquake broke it into pieces. (Image credit: Department of Special Collections and University Archives, Stanford University Libraries)

As part of the class, Algaze and other students picked an object from Stanford’s collections to research and present in an exhibit at the Stanford Archaeology Center.

“I just had this gut feeling when I saw those three boxes,” Algaze said. “I knew there had to be something important in there.”

Algaze’s research into the coffin advanced when she discovered two inscribed fragments. To translate the text, Algaze consulted with Egyptologists Foy Scalf at the University of Chicago and Barbara Richter at the University of California, Berkeley, and other experts on demotic, the ancient Egyptian written language.

Algaze found that the name of the buried woman was Senchalanthos. One part of the inscription translated to: “May her name rejuvenate every day.”

Excavated in the area of present-day Egyptian city Akhmim, the mummy case dates to the Greco-Roman period of ancient Egypt, somewhere between 100 BCE and 100 CE. But the style of the grammar used in the inscription indicates that the mummy case was buried during the Roman period, which started at 30 BCE, Algaze said, citing her consultation with Scalf.

“There are so few inscriptions from that era of Egypt that the experts I contacted were really excited and eager to take a look and help me out,” Algaze said.

The process of digging through Stanford’s vast collection of objects always reveals something interesting, said Hodge, academic curator and collections manager of the Stanford University Archaeology Collections.

But uncovering previously unknown inscriptions on pieces of the ancient cartonnage was an especially unique find, she said.

Ariela Algaze found that two fragments of the cartonnage she studied contained ancient Egyptian writing. (Image credit: Christina Hodge)

“It’s been one of the most surprising discoveries in the collection so far,” said Hodge, who has been in charge of organizing and cataloging Stanford’s archaeology materials for the past four years. “Inscriptions are one of those things Egyptologists get especially excited about, so you would think that someone would have noted down that this cartonnage has writing on it. The fact that this wasn’t documented is very unusual.”

Hodge said it’s possible that the inscriptions were mentioned somewhere, but those records did not survive the 1906 earthquake.

This ancient mummy case is one of three in the Stanford University Archaeology Collections. The other two, which were also damaged in the earthquake, include partial cartonnage that covered only the head and pectoral area of the coffin, Hodge said.

“Considering how much damage the earthquake caused, pulverizing many of the objects, it’s also serendipitous that the writing survived on one of the bigger fragments of the cartonnage,” Hodge said.

For Algaze, being able to tell the public who was buried in that mummy case is the most important part of her research experience.

“It’s all about restoring dignity to fragmented objects,” Algaze said. “To be able to say the name of a woman who was in a coffin that withstood two earthquakes and traveled all the way from Egypt here is incredible. That’s the most powerful thing to me.”

Some pieces of the mummy case are now on display at the Stanford Archaeology Center until May 2019.