Earth likely to cross critical climate thresholds even if emissions decline, Stanford study finds

Artificial intelligence provides new evidence our planet will cross the global warming threshold of 1.5 degrees Celsius within 10 to 15 years. Even with low emissions, we could see 2 C of warming. But a future with less warming remains within reach.

A new study has found that emission goals designed to achieve the world’s most ambitious climate target – 1.5 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels – may in fact be required to avoid more extreme climate change of 2 degrees Celsius.

Already, the world is 1.1 degrees Celsius hotter on average than it was before fossil fuel combustion took off in the 1800s. More extreme rainfall and flooding are among the litany of impacts from that warming. (Image credit: Lisa Maree Williams/Stringer/Getty Images)

The study, published Jan. 30 in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, provides new evidence that global warming is on track to reach 1.5 degrees Celsius (2.7 Fahrenheit) above pre-industrial averages in the early 2030s, regardless of how much greenhouse gas emissions rise or fall in the coming decade.

The new “time to threshold” estimate results from an analysis that employs artificial intelligence to predict climate change using recent temperature observations from around the world.

“Using an entirely new approach that relies on the current state of the climate system to make predictions about the future, we confirm that the world is on the cusp of crossing the 1.5 C threshold,” said the study’s lead author, Stanford University climate scientist Noah Diffenbaugh.

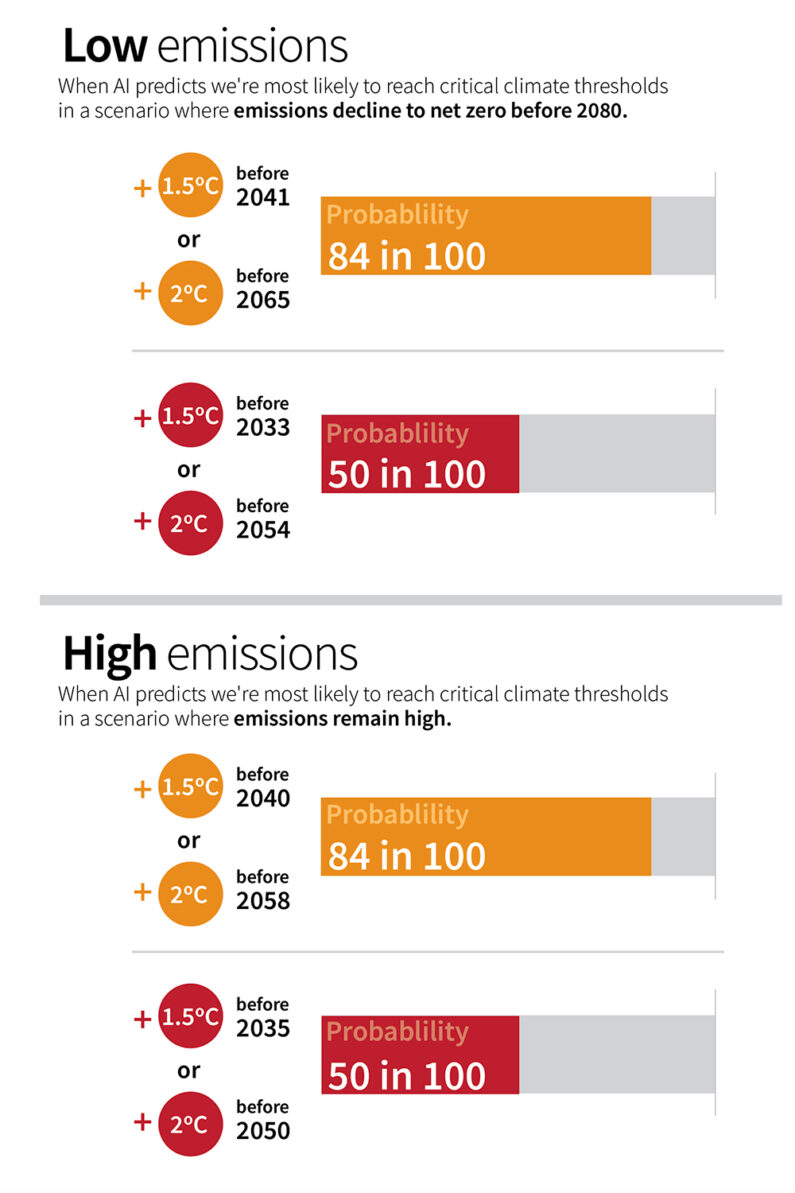

If emissions remain high over the next few decades, the AI predicts a one-in-two chance that Earth will become 2 degrees Celsius (3.6 Fahrenheit) hotter on average compared to pre-industrial times by the middle of this century, and a more than four-in-five chance of reaching that threshold by 2060.

According to the analysis, which Diffenbaugh co-authored with Colorado State University atmospheric scientist Elizabeth Barnes, the AI predicts the world would likely reach 2 C even in a scenario in which emissions decline in the coming decades. “Our AI model is quite convinced that there has already been enough warming that 2 C is likely to be exceeded if reaching net-zero emissions takes another half century,” said Diffenbaugh, who is the Kara J Foundation Professor and Kimmelman Family Senior Fellow in the Stanford Doerr School of Sustainability.

This finding may be controversial among scientists and policymakers, Diffenbaugh said, because other authoritative assessments, including the most recent report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, have concluded that the 2-degree mark is unlikely to be reached if emissions decline to net zero before 2080.

Why does half a degree matter?

Crossing the 1.5 C and 2 C thresholds would mean failing to achieve the goals of the 2015 Paris Agreement, in which countries pledged to keep global warming to “well below” 2 C above pre-industrial levels, while pursuing the more ambitious goal of limiting warming to 1.5 C.

Already, the world is 1.1 degrees Celsius (2 Fahrenheit) hotter on average than it was before fossil fuel combustion took off in the 1800s, and the litany of impacts from that warming includes more frequent wildfires, more extreme rainfall and flooding, and longer, more intense heat waves.

Because these impacts are already emerging, every fraction of a degree of global warming is predicted to intensify the consequences for people and ecosystems. As average temperatures climb, it becomes more likely that the world will reach thresholds – sometimes called tipping points – that cause new consequences, such as melting of large polar ice sheets or massive forest die-offs. As a result, scientists expect impacts to be far more severe and widespread beyond 2 C.

In working on the new study, Diffenbaugh said he was surprised to find the AI predicted the world would still be very likely to reach the 2 C threshold even in a scenario where emissions rapidly decline to net zero by 2076. The AI predicted a one-in-two chance of reaching 2 C by 2054 in this scenario, with a roughly two-in-three chance of crossing the threshold between 2044 and 2065.

It remains possible, however, to bend the odds away from more extreme climate change by quickly reducing the amount of carbon dioxide, methane, and other greenhouse gases being added to the atmosphere. In the years since the Paris climate pact, many nations have pledged to reach net-zero emissions more quickly than is reflected in the low-emissions scenario used in the new study. In particular, Diffenbaugh points out that many countries have net-zero goals between 2050 and 2070, including China, the European Union, India, and the United States, as do many non-state actors, including Stanford University.

“Those net-zero pledges are often framed around achieving the Paris Agreement 1.5 C goal,” said Diffenbaugh. “Our results suggest that those ambitious pledges might be needed to avoid 2 C.”

AI trained to learn from past warming

Previous assessments have used global climate models to simulate future warming trajectories; statistical techniques to extrapolate recent warming rates; and carbon budgets to calculate how quickly emissions will need to decline to stay below the Paris Agreement targets.

For the new estimates, Diffenbaugh and Barnes used a type of artificial intelligence known as a neural network, which they trained on the vast archive of outputs from widely used global climate model simulations.

Once the neural network had learned patterns from these simulations, the researchers asked the AI to predict the number of years until a given temperature threshold will be reached when given maps of actual annual temperature anomalies as input – that is, observations of how much warmer or cooler a place was in a given year compared to the average for that same place during a reference period, 1951-1980.

To test for accuracy, the researchers challenged the model to predict the current level of global warming, 1.1 C, based on temperature anomaly data for each year from 1980 to 2021. The AI correctly predicted that the current level of warming would be reached in 2022, with a most likely range of 2017 to 2027. The model also correctly predicted the pace of decline in the number of years until 1.1 C that has occurred over the recent decades.

“This was really the ‘acid test’ to see if the AI could predict the timing that we know has occurred,” Diffenbaugh said. “We were pretty skeptical that this method would work until we saw that result. The fact that the AI has such high accuracy increases my confidence in its predictions of future warming.”

This research was supported by Stanford University and the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Biological and Environmental Research as part of the Program for Climate Model Diagnosis and Intercomparison Project.

Diffenbaugh is a professor of Earth system science, a senior fellow at the Stanford Woods Institute for the Environment, and the Olivier Nomellini Family University Fellow in Undergraduate Education.