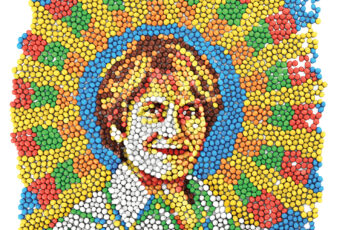

Stanford’s Carolyn Bertozzi wins Nobel in chemistry

Stanford chemist Carolyn Bertozzi was awarded the Nobel Prize in chemistry for her development of bioorthogonal reactions, which allow scientists to explore cells and track biological processes without disrupting the normal chemistry of the cell.

This story was updated on Wednesday, Oct. 6, at 1:23 p.m. PDT.

Carolyn Bertozzi received an early birthday gift this year.

Bertozzi, the Anne T. and Robert M. Bass Professor in the School of Humanities and Sciences and a professor of chemistry, with courtesy appointments in Chemical & Systems Biology and Radiology, has won the 2022 Nobel Prize in chemistry – just a few days before her 56th birthday next Monday.

Go to the web site to view the video.

She shares the $10 million Swedish kronor (about $1 million USD) prize equally with Morten Meldal, professor at University of Copenhagen; and K. Barry Sharpless, PhD ’68, professor at Scripps Research “for the development of click chemistry and bioorthogonal chemistry.” The Nobel Prize in chemistry is awarded by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences.

Bertozzi was recognized for founding the field of bioorthogonal chemistry, a set of chemical reactions that allow researchers to study molecules and their interactions in living things without interfering with natural biological processes. Bertozzi’s lab first developed the methods in the late 1990s and early 2000s. Since then, her lab and others have used them to answer fundamental questions about the role of sugars in biology, to solve practical problems, such as developing better tests for infectious diseases, and to create a new biological pharmaceutical that can better target tumors, which is now being tested in clinical trials.

“I could not be more delighted that Carolyn Bertozzi has won the Nobel Prize in chemistry,” said Stanford President Marc Tessier-Lavigne. “In pioneering the field of bioorthogonal chemistry, Carolyn invented a new way of studying biomolecular processes, one that has helped scientists around the world gain deeper understanding of chemical reactions in living systems. Her work has had remarkable real-world impact, unleashing new diagnostic and therapeutic approaches to treat disease. Carolyn is so deserving of this honor, and all of us at Stanford are tremendously proud to call her one of our own.”

Early Wednesday morning, Bertozzi held her hands to her face, in shock. “They call and I’m not even awake … Starbucks isn’t even open yet,” she exclaimed while in her pajamas at her kitchen table in Palo Alto.

By 3 a.m., Bertozzi had nearly three dozen voicemails. “This is how it’s going to be all day. This is insane,” she said. “Maybe I should cancel meetings.”

Pausing between interviews about two hours later to check her messages, Bertozzi said, “My family is already booking their flights to Stockholm. It’s hilarious. Go back to sleep!”

Sugar highs

At 1:43 a.m., Bertozzi was awakened by a phone call from a Nobel committee member who, in addition to breaking the momentous news, told her, “You have 50 minutes to collect yourself and wait until your life changes.”

Instructed not to share the announcement outside of her tightest inner circle, the first person Bertozzi called was her father, William Bertozzi, a retired physics professor from MIT. “He’s 91 and, of course, he was just overjoyed,” said Bertozzi. “And then he called my sisters for me, and we’ve been texting. One of my sisters and my dad watched it live.”

Bertozzi’s development of bioorthogonal chemistry – a term Bertozzi coined, which means “not interacting with biology” – grew out of an interest in complex carbohydrate molecules, called glycans. Along with proteins and nucleic acids such as DNA, they are one of the key building blocks of life and also one of the least well understood – in large part because they are hard to make in the lab and, when Bertozzi began her career, one of the hardest to analyze.

Then, after working for years to understand the structure and function of one glycan, Bertozzi had an idea: What if she could attach fluorescent tags to sugar molecules, so that she could literally see where the sugars were in live cells? The tricky part wasn’t attaching a fluorescent tag, however. Instead, it was attaching that tag in a way that didn’t interfere with what the sugar and all the other molecules in the cell were supposed to be doing.

Bertozzi, then a professor of chemistry at the University of California, Berkeley, and colleagues tried a number of different chemical reactions to make it work, but eventually dug up a roughly hundred-year-old process called the Staudinger reaction, and modified it for their purposes. The reaction, now known as Staudinger ligation or Staudinger-Bertozzi ligation, allowed her to attach fluorescent tags to specially modified sugar molecules after the sugar molecules had already been incorporated into a cell – all without reactions that would muck up a cell’s biochemistry. For the first time, chemists could actually see how sugars were distributed on the surface of a cell, but the discovery also opened the door to studying chemistry as it actually happens in living things, one of the most complex chemical environments imaginable.

The next step forward in bioorthogonal chemistry built upon Sharpless and Meldal’s work in click chemistry – a form of simple, reliable chemistry where molecular building blocks snap together quickly and efficiently. Looking for a way to speed up her bioorthogonal process, Bertozzi saw potential in a reaction Sharpless and Meldal discovered independently, called copper-catalyzed azide-alkyne cycloaddition. This reaction, already the crown jewel of click chemistry, required modification for use in living cells because it would introduce copper into a cell, which is toxic. Inspired by chemistry from classic textbooks, Bertozzi’s lab modified the reaction, resulting in copper-free click chemistry. This faster version of bioorthogonal chemistry allowed Bertozzi to track the activity of glycans in cells over time.

Since their development, Bertozzi’s bioorthogonal reactions and derivatives thereof have been used to study how cells build proteins and other molecules, to develop new cancer medicines, and to produce new materials for energy storage, among many other applications.

“Research at the interface of chemistry and biology has always been where I practice, and having a Nobel Prize in chemical biology is really great for the field,” said Bertozzi, who is also an investigator with the Howard Hughes Medical Institute (HHMI), which has helped fund her work since 2000. “The field is not so old, but the impact is clear.”

Despite having had only a few hours to reflect on her new status as a Nobel laureate, Bertozzi is already considering ways to make the most of the honor. “I’m the same person I was at 1 a.m., but I’m realizing that my voice now has a platform, and I’m thinking about how to use that.”

Translating discovery

In recent years, Bertozzi said, she has grown increasingly interested in applying her decades of experience as a chemist to medicine. In 2015, Bertozzi moved to Stanford to help lead Sarafan ChEM-H, an institute devoted to bridging chemistry, engineering, and medicine to better understand human health and treat disease. In 2020, she was named Baker Family Director of Sarafan ChEM-H, and has worked to build stronger connections between foundational chemistry and biology researchers and clinical researchers across the street at Stanford Medicine. In her own research, she has helped develop new, lower-cost tests for tuberculosis, more efficient tests for HIV, and a new class of medicines that can clear disease-causing proteins from the surface of cells.

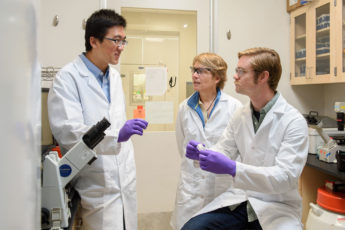

She is also known as a prolific mentor, having advised more than 250 undergraduates, graduate students, and postdoctoral fellows. “I’ve had a lot of impact, so I’m the vehicle through which the spotlight gets cast onto the field and then also onto all the amazing students and postdocs that I’ve had over a 25-year career,” Bertozzi said.

“You could tell that momentous science was happening in her lab,” said Fred Tomlin, a former graduate student in Bertozzi’s lab. “Not only did bioorthogonal chemistry create an entirely new field of research, but over time, she shaped that field to directly benefit humanity.”

Former graduate student Ellen Sletten praised Bertozzi for being an incredible teacher, mentor, and advocate for women and for the LGBTQ communities. “Being a woman in science and being trained by her, it was really inspiring to see her speaking about her challenges and I’m so grateful that she paved the way because it’s made it much easier for all of us in the next generations that have followed,” said Sletten, who is now an associate professor at UCLA.

Bertozzi founded and continues to lead the Sarafan ChEM-H Chemistry-Biology Interface Predoctoral Training Program, which helps train graduate students to bridge the gap between chemistry, biology, and medical research. Together with Chaitan Khosla, the Marc and Jennifer Lipschultz Director of the Stanford Innovative Medicines Accelerator (IMA), she launched the Postbaccalaureate Program in Target Discovery to prepare recent college graduates from diverse and historically underserved backgrounds to apply for doctorate programs in the sciences. Her commitment to mentorship and to increasing diversity in science was recognized with the 2022 Lifetime Mentor Award from the American Association for the Advancement of Science.

Amidst all the hustle and bustle of documenting and celebrating this latest achievement, members of Stanford’s communications team couldn’t help but notice that Bertozzi keeps a Christmas tree year-round in her living room. When asked about it, she explained, “Every day is Christmas,” before pausing to add, “Today is definitely Christmas.”

Bertozzi is a member of the National Academy of Sciences, the National Institute of Medicine, and the National Academy of Inventors; a fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences; and an Investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute since 2000. She was awarded a MacArthur Fellowship in 1999 at the age of 33, making her one of the youngest to receive that recognition. At Stanford, Bertozzi is also a member of Stanford Bio-X, the Wu Tsai Human Performance Alliance, the Maternal & Child Health Research Institute (MCHRI), the Stanford Cancer Institute, and the Wu Tsai Neurosciences Institute.

Chelcey Adami, Bjorn Carey, Melissa De Witte, and Rebecca McClellan contributed to the reporting of this story.