Stanford historians put 2021 into its historical context

In the fall quarter course, History of 2021, Stanford faculty offered historically informed reflections on some of the year’s most pressing issues and showed students how many of today’s problems are inherited from the past.

Between the Jan. 6 attacks on the U.S Capitol, the withdrawal of American and NATO forces from Afghanistan, escalating anti-Asian violence across the country, not to mention an unrelenting global pandemic, it could be said that events of the past year are “one for the history books.”

How historians view events that defined 2021 and the present period was the topic of the fall quarter humanities course, History of 2021. Every week, nearly 140 Stanford students gathered to hear a different faculty member from the History Department relate a current affairs issue to their area of historical expertise.

“We hear a lot about living in unprecedented times. Studying history can help nuance these claims and challenge assumptions of contemporary exceptionalism,” said Fiona Griffiths, a professor of history in the School of Humanities and Sciences and the course’s faculty coordinator. “A historic perspective can enable or enhance critical attention to contemporary events – much of what we saw happen in the news this past year built on long-standing power dynamics, whether domestic or international, that are not always self-evident.”

Griffiths and her colleagues developed the course as a place for Stanford students to reflect on the upheavals of the past few years and to consider what set of historic circumstances stand behind them.

For example, Jonathan Gienapp showed how resistance to Electoral College reform has often been rooted in race rather than discrepancy in the size of states, and Gordon Chang explained how the current surge of anti-Asian violence in America is a long-standing pattern that goes back to the mid-19th century, when immigration from China to the U.S. began increasing.

Some lectures focused on grave humanitarian concerns, such as the detention of Uyghur Muslims in China or the difficult migration of low-wage workers across India. Other faculty showed students ways in which previous disease outbreaks – like the Black Death in Renaissance Italy and yellow fever in antebellum New Orleans – can inform our own understanding of the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic.

“Every single lecture in History of 2021 had an ‘aha!’ moment where, all of a sudden, a completely new vista and understanding of our present was opened for us through the speaker’s careful explication of the past,” Griffiths said.

Stanford News Service spoke to each of the faculty members involved in the teaching of the course and asked them to describe, in their own words, what a historical perspective can bring to bear on our understanding of present-day conflicts and challenges.

Jonathan Gienapp’s lecture, titled “Electing the U.S. President: The Electoral College,” focused on the origins of the Electoral College and attempts to reform it.

Tom Mullaney delivered a lecture titled “China’s Border Crises: Xinjiang, Hong Kong, Taiwan and the Legacies of Empire” that focused on a pair of crises unfolding in China: protests in Hong Kong and the internment of Uyghur Muslims in northwest China.

“Democracy is predicated on public debate, and that debate should ultimately turn on the merits of the question, not historical myths.”

– JONATHAN GIENAPP, ASSISTANT PROFESSOR OF HISTORY

James Campbell’s lecture, “Monumental Questions,” sought to provide some historical context for understanding the current controversy over Civil War monuments.

Gordon Chang delivered a lecture titled “Anti-Asian Violence in America” that examined the long history of anti-Asian hate crime in the United States.

“But if we look at this history, we can have a better appreciation of what people have gone through … including the long history of suffering, but also contributions of Asians to the country; I think people will have a different view of those living in the present.”

– GORDON CHANG, PROFESSOR OF HISTORY

Partha Shil delivered a lecture titled “Laboring Lives and the Pandemic in South Asia, c. 2020-21” about the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the Indian working classes and the urban poor over the last two years.

Robert Crews gave a lecture titled “The Year the Afghan War Ended?” that used history to show how despite the U.S. withdrawal of troops from Afghanistan in August 2021, conflict in the country is far from over.

“It’s easy to think of Afghanistan as a place that’s far from us, alien and wholly different. It’s hard to think about the ways in which we have a shared legacy, but it’s a place that has been very much part of our past. Thinking about the war is so important because we have had so many Americans who have made enormous sacrifices there.”

– ROBERT CREWS, PROFESSOR OF HISTORY

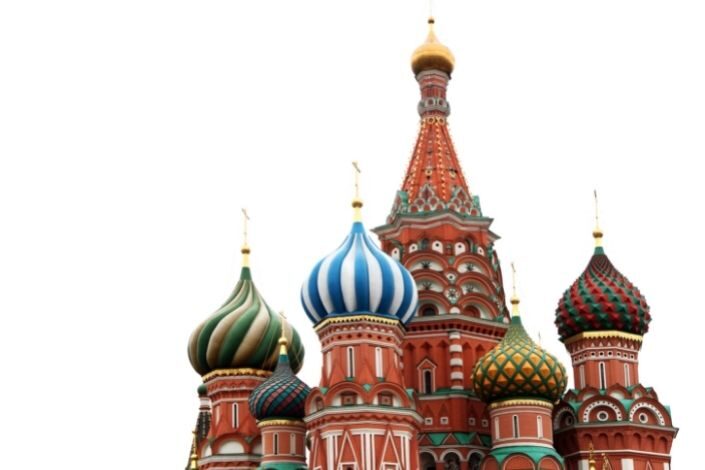

Nancy Kollmann, along with Amir Weiner, delivered a lecture called “Russia’s Love Affair with Authoritarianism: From Ivan the Terrible to Putin.” Kollmann focused on the origins of Russia’s authoritarian and autocratic rule to show students how Putin follows in this long tradition.

Amir Weiner, along with Nancy Kollmann, delivered a lecture called “Russia’s Love Affair with Authoritarianism: From Ivan the Terrible to Putin.” Weiner focused on the Communist era and how the collapse of the Soviet Union shaped Russian politics today and its president, Vladimir Putin.

“I think most people have tended to study a moment like the Black Death as the history of the very dead and gone that leaves behind a compelling record, but when you re-read that record in light of our own experience, it sounds different, doesn’t it?”

– PAULA FINDLEN, PROFESSOR OF HISTORY

Paula Findlen delivered a lecture titled “The Plague Generation: Love, Death, Healing and Friendship in a Time of Pandemic,” where she discussed The Decameron, a collection of 100 stories written by the Italian poet Giovanni Boccaccio during the mid-14th century as the bubonic plague ravaged Italy.

Kathryn Olivarius delivered a lecture titled “Public Health as Public Wealth: Yellow Fever, COVID-19 and the Politics of Immunity” that examined the individualistic approaches to COVID immunity in parallel to the repeated yellow fever epidemics that killed some 150,000 people between the Louisiana Purchase of 1803 and the Civil War in 1861.