Stanford English professor explores the oceans through many lenses

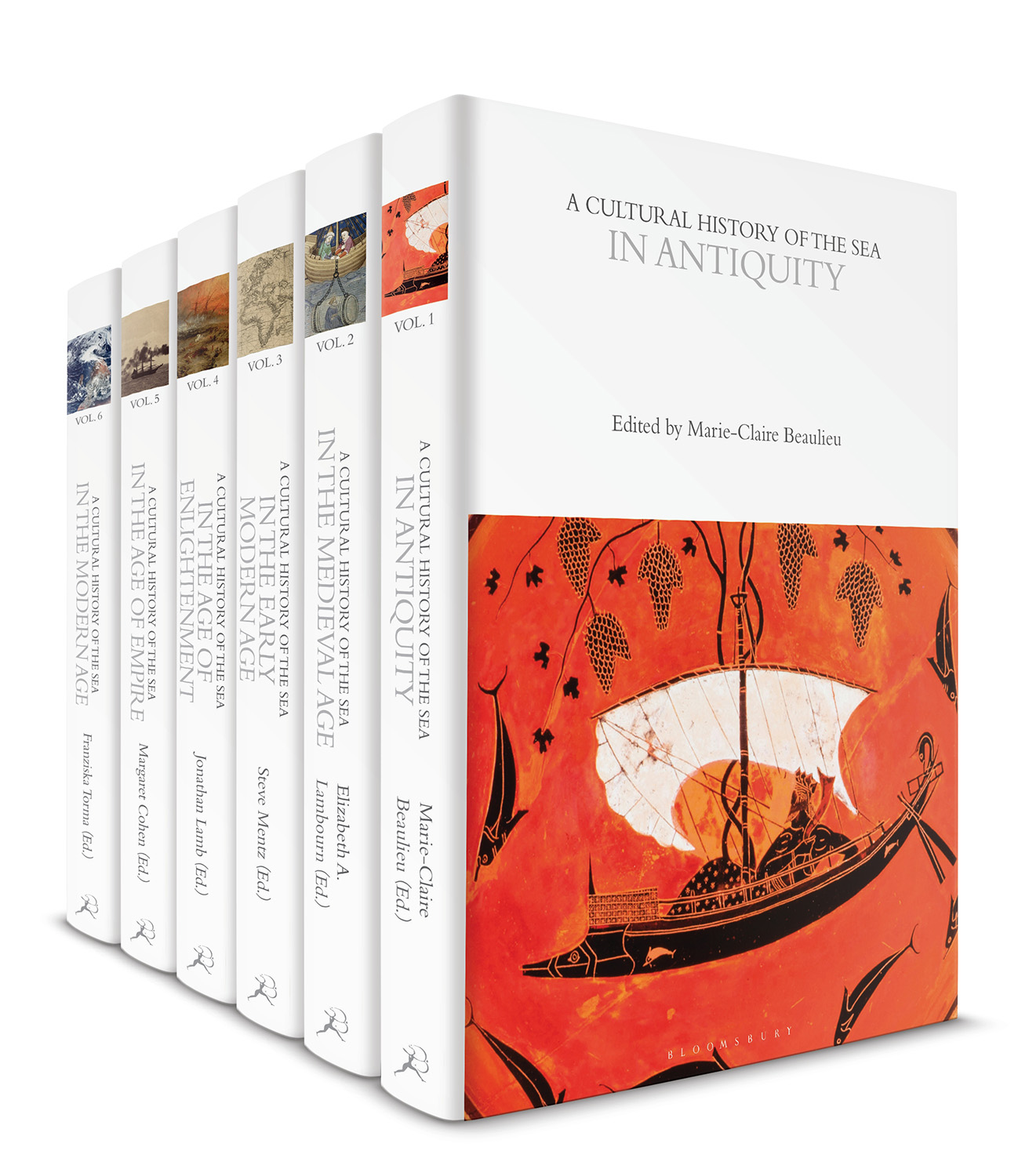

With a publication date coinciding with Earth Day, a new, six-volume set edited by Stanford English Professor Margaret Cohen explores the cultural history of Earth’s oceans from antiquity to the modern era.

English Professor Margaret Cohen can often be found paddling her surfboard out into the Pacific Ocean, sharing the beautiful natural habitat with California sea lions and harbor seals. Her appreciation for the magic and mystery of the ocean and its influence on human history spans both her personal and professional life. Now, she shares her passion for the ocean as the general editor of a new, six-volume series, A Cultural History of the Sea (Bloomsbury Academic, 2021), fittingly being released on Earth Day, April 22.

A new book series on the cultural history of the sea looks at this vital resource thorough historical, literary and cultural perspectives. An image from the series: Hendrick Cornelisz Vroom, A Number of East Indiamen off the Coast, c. 1600–1630. (Image credit: © Wikimedia Commons [public domain])

From antiquity to the modern era, Cohen’s series shows the vital role oceans have played – something that people often overlook. Sometimes it takes a major disturbance for people to realize their significance. A recent case in point: When the ship Ever Given was stranded in the Suez Canal, it not only blocked the movement of cargo, but also caused massive disruptions in supply chains throughout the world. “Now people realize over 90 percent of the world’s commerce is by sea,” Cohen said.

Cohen’s new book series shines a renewed spotlight on this vital resource thorough a variety of lenses and examines oceanic history through historical, literary and cultural perspectives.

Over the past 30 years, the field of oceanic studies has emerged in the humanities as an interdisciplinary field. Incorporating earlier scholarship, which focused on maritime transport, naval warfare and global exploration often within the context of nations, the new field takes a broader approach.

“Today, oceanic studies aim to tell the stories of all who have traveled the seas,” writes Cohen, the Andrew B. Hammond Professor in French Language, Literature, and Civilization in the School of Humanities and Sciences. These travelers include adventurers, forced migrants, professionals and animals.

Each volume features established scholars as well as newer voices, Cohen said, and their work represents original research. As general editor and editor of the volume covering the 19th century, she recruited and worked with scholars whose expertise spans the oceans of the globe, from the Mediterranean and the Atlantic to the Indian and Pacific oceans.

A new, six-volume series, A Cultural History of the Sea, is fittingly being released on Earth Day, April 22. (Image credit: Courtesy Bloomsbury Academic)

A feature of the series is chapter themes that run through all the volumes so that a reader might explore by area of interest, such as “Networks,” rather than by historical periods. Theme topics, which the volume editors worked together to choose, reflect new ways of exploring history. “We tried to decolonize representations of the ocean,” Cohen explained. “Instead of ‘War and Empire’ as themes, as had been used previously, we turned it into ‘Conflicts.’ There are so many ways the sea is a violent place.”

For example, the volume The Age of Empire (1800-1920) examines a range of conflicts throughout the 19th century, including the violence that arose from how ships managed their crew, to slavery, to battles at sea between military vessels. But there also was the unpredictable violence of the elements, a theme of life on the seas throughout the eras.

“The themes that run from antiquity to the 20th century give people another way to connect concepts across many volumes, which is important because some things about the sea exceed centuries and are different from history on land,” Cohen said.

For example, the years 1769 to 1989 form one period in the history of navigation, but in the series spans three volumes. As Cohen points out, in 1769, British engineer John Harrison perfected a chronometer that kept accurate time throughout a long journey. But that technology was not widely used on ships until the 19th century and celestial navigation remained the norm. It wasn’t until 1989, with the invention of the global positioning system, that celestial navigation became obsolete.

Another recent shift in oceanic studies is a greater understanding of humankind’s harmful impact on marine environments, once thought to change at a geological pace. Now, those impacts can be seen within a lifetime, as with global warming leading to the melting of ice caps at the Earth’s poles and the impacts of overfishing on the environment, Cohen said. Not only do those changes affect the long-held view of the ocean as an inexhaustible natural resource, the melting of the polar ice caps may also shift or raise tensions between nations as the long-sought Northwest Passage for trade becomes a global reality – topics that are addressed in the final volume in the series, The Modern Age.

English Professor Margaret Cohen’s passion for the ocean spans both her personal and professional life. (Image credit: Sylvain Cazenave)

Cohen has long been captivated by oceans, having used her expertise in comparative literature to produce The Novel and the Sea (Princeton University Press, 2010), an examination of maritime literature. But she notes that general interest in the world’s oceans has ebbed and flowed.

“There have been eras across history when oceans were on the minds of decision makers,” Cohen said, referencing the height of the British Empire, when maritime power was an imperative for achieving colonial aspirations. However, in much of the 20th century, people were less concerned with the oceans and focused on space exploration instead, she said.

Another part of ocean life explored in the series are underwater cables, which first sped up communications when they were laid in the 19th century and still account for much of the world’s connections. Figures from 2015 showed that more than 98 percent of international data travels through submarine space. In the 19th century, information became transmissible underwater with the inception of transoceanic cable networks that were linked in 1866 across the Atlantic. “In 1870, overland and undersea links were joined up to enable cable transmission from London to Mumbai, creating another medium of passage between Atlantic and Indian Ocean worlds,” Cohen writes.

Her scholarly interest in oceanic studies came from maritime literature such as Herman Melville’s Moby-Dick and Joseph Conrad’s The Mirror of the Sea – books that demonstrate the sea’s appeal, power and ferocity. Now, the professor finds that the ocean is her place to relax and reset, as long as she has her wetsuit and surfboard to admire and tackle the cold Pacific Ocean’s formidable waves.