Hard-to-quantify emissions are the next frontier for Stanford sustainability goals

Stanford is celebrating Earth Day with a week of virtual events and is looking ahead to additional ways the campus can reach ambitious net-zero emissions goals, including tackling emissions from campus food, goods, travel and investments.

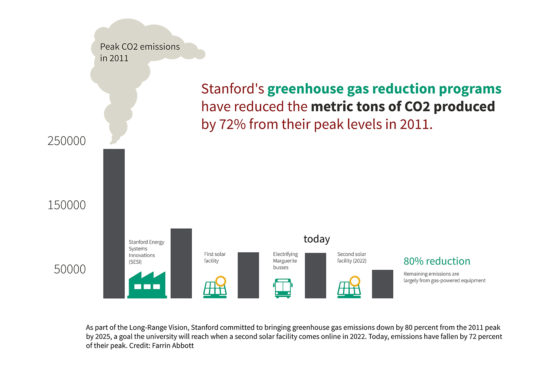

Even before the pandemic, Stanford’s emissions from campus operations, which include providing electricity, heating and cooling to buildings and running campus shuttles, had fallen by 72% from their peak 2011 levels. Emissions will achieve an 80% reduction by 2022 when a new solar facility comes online, which is 3 years ahead of the 2025 deadline Stanford set for reaching that goal.

But those numbers only reflect relatively easy-to-track emissions. Now, Stanford is beginning to measure what are known as Scope 3 emissions, the indirect emissions generated by things such as growing and transporting food, travel, investments and producing the goods we buy.

Tackling Scope 3 emissions will be critical for achieving the goals laid out last year when Stanford’s Board of Trustees signed a resolution to reach at least net-zero greenhouse gas emissions from its operations and endowment by 2050. The Faculty Senate later urged the university to revise that target date to 2040 and encouraged faculty, students and staff to accelerate efforts to reduce emissions in their own lives.

A living lab

Sally Benson, professor of energy resources engineering, has been working on measuring Scope 3 emissions produced through growing, producing, packaging and transporting food and goods. She hopes her work will have benefits beyond campus by helping governments, businesses and other universities reach their own emissions goals.

“If you want to be on the cutting edge of reducing emissions you are going to have to tackle Scope 3 too,” Benson said. “For me, what’s important isn’t just that we reduce ours. What we do doesn’t matter unless we can provide tools that others can use to replicate our success.”

With Earth Day approaching April 22, Stanford is looking ahead to this next frontier while also encouraging other areas of personal and policy sustainability solutions through a series of virtual events.

Food, travel and goods

Benson’s interest in Scope 3 emissions began more than a decade ago when she had her students evaluate their own carbon footprints.

“Everyone knows flying is really bad,” she said. “But we found the stuff we buy was the biggest part of the footprint and it’s completely invisible.”

These emissions are invisible largely because they are so difficult to quantify. Benson and a graduate student are working on a tool that will make quantifying Scope 3 emissions easier, starting with those produced by the lowest-hanging fruit – food.

Tools exist that attempt to calculate all the emissions generated by a product’s journey from raw materials to the hands of a purchaser, Benson says. But some calculate based on the weight and others based on cost, and the two aren’t comparable. It turns out goods appear to produce far less emissions when calculated by cost, which is what most tools use because the data is easier to get. And because the tools don’t report how they calculate emissions, the results are inconsistent and Benson and Grekin can’t tell which are correct.

“It isn’t apples to apples,” said Rebecca Grekin, the graduate student working with Benson. Two organizations ordering the same apples could report very different emissions – up to a three-fold difference, according to Benson – depending on the tool they use. In order to tackle Scope 3 emissions, they needed to start with a tool they could trust.

In collaboration with Residential & Dining Enterprises and the Office of Sustainability, Grekin has started from scratch, calculating emissions generated by the food actually served on Stanford campus. She is also coordinating with 10 other universities that have given her their own food data.

Grekin added that Stanford had already made great strides in reducing emissions in the food served, in particular by offering many choices as alternatives to carbon-intensive beef.

“When you compare the food served on campus to the typical American diet they’ve had a lot of initiatives to make improvements,” Grekin said.

Creating a tool to quantify the emissions produced by food served on campus has been the focus of Grekin’s master’s degree, but it’s not her final goal.

“The tool can also be edited to categorize other things,” she said.

For her PhD project, which she’ll begin with Benson next year, Grekin is going to begin looking at other sources of emissions including products like office goods. Eventually, Grekin says, the tool will be used to help Stanford evaluate and then reduce sources of emissions, and be made available for other businesses, governments or universities that wish to do the same.

Many campus organizations have taken pledges to reduce emissions and have done a good job with energy efficiency and renewable energy sources, Benson said. She suggested that organizations with Scope 3 commitments could form a buying group to support emerging office products or food sources that have lower emissions. Benson added that her group’s focus on food and goods is just one part of a multi-year effort Stanford has launched to reduce its Scope 3 emissions, under the leadership of Randy Livingston, vice president of business affairs, chief financial officer and university liaison for Stanford Medicine. The program will be advised by a working group including faculty, staff and an undergraduate and graduate student.

A helping hand

Reducing your carbon footprint – the emissions your actions directly produce – is important, Grekin said, but can feel discouraging. Instead, Grekin focuses on what she calls her handprint, or the emissions her influence has helped to reduce. Working on Scope 3 emissions is a way of increasing her handprint and having an even larger impact.

“You need to not only look at the emissions you cause but also the emissions reductions you cause,” she said. “With this work, I can have a larger handprint by helping others become aware and reduce their own emissions.”

Earth Day virtual events

In observance of Earth Day, Stanford’s Office of Sustainability is hosting a week of virtual events that celebrate campus commitments and support community sustainability efforts, including virtual tours of Codiga, discussions of how to sort waste and save water and energy at home and a sustainable cooking demonstration. The Stanford Woods Institute for the Environment will have additional scientific panels on wildland fire, sustainable development, human and planetary health and environmental justice.

The events also include a panel on carbon pricing – a policy mechanism that puts a price on carbon emissions as an incentive for industries to reduce their own emissions. The panel will be moderated by Catherine Luo ’23, who has been working with faculty and student organizations encouraging Stanford to sign a letter acknowledging carbon pricing as an indispensable step to effectively combat climate change.

The Associated Students of Stanford University have passed a resolution calling on the university to sign the letter, address its Scope 3 emissions and implement a carbon pricing system on campus.

“Carbon pricing is a critical part of tackling climate change,” said Luo, who is majoring in Earth systems and economics. “When I heard about other higher education institutions signing on to support the carbon pricing letter I thought advocating for that at Stanford was a way I could make a difference.”

She’s been working with those Stanford faculty who support carbon pricing as a way of gaining attention for the policy solution among students, other faculty and university leadership. Although carbon pricing has many supporters, other faculty members support alternative mechanisms for combating climate change.

The panel, which takes place April 21 at 4 p.m., includes Lawrence Goulder, Shuzo Nishihara Professor of Environmental and Resource Economics, Frank Wolak, Holbrook Working Professor of Commodity Price Studies, John Weyant, professor of management science and engineering and Robert Litterman, from Kepos Capital. It is intent is to help educate the community about the nuances of carbon pricing and how it may be incorporated into future climate policy at the national level.

Luo has worked on her carbon pricing initiative with Kunal Sinha ’24, who is a member of Fossil Free Stanford. “We’ve gotten a lot of support from faculty members who think carbon pricing is an important policy solution,” he said. Next year, Luo is thinking about doing research on carbon pricing and plans to continue advocating for it during her time at Stanford.

Luo will be the initial undergraduate student representative on the working group advising the Scope 3 effort overseen by Randy Livingston. “Carbon pricing is one of many mitigation initiatives that the Scope 3 program and working group will consider.”