Stanford historian traces the colonial origins of conflict diamonds in Namibia

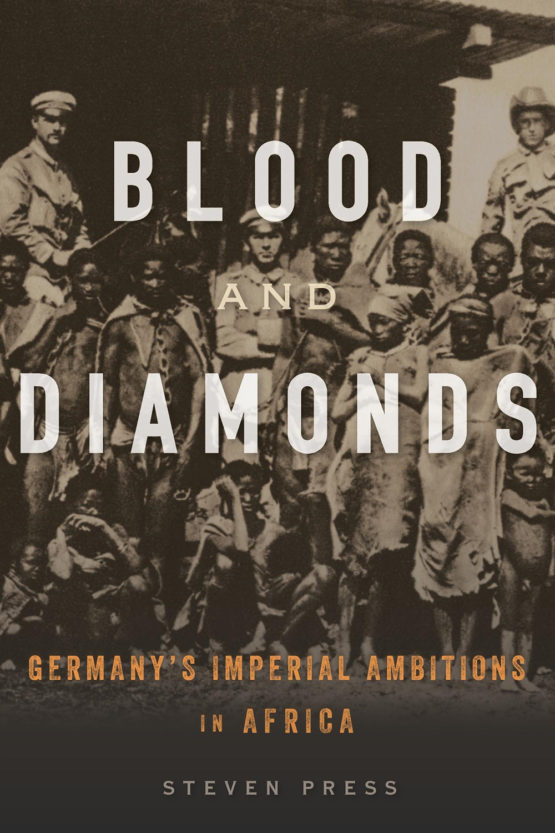

New book by Stanford historian Steven Press unearths previously obscured connections between German colonial activities and the world diamond market.

When Stanford historian Steven Press was trying to unearth hidden narratives about Germany’s colonial activities in Southwest Africa’s highly secretive diamond industry, he pursued that age-old maxim to “follow the money.”

Steven Press is an assistant professor of history in the School of Humanities and Sciences. His new book, Blood and Diamonds, traces the devastating cost of diamond mining and German colonial domination in Namibia during the late 18th and 19th centuries. (Image credit: Pui Shiau)

Chasing that trail led to some disturbing discoveries about the full extent of Germany’s ruthlessness as it pursued its economic aspirations in the African country now known as Namibia in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

In his new book Blood and Diamonds (Harvard University Press, 2021), Press outlines how from 1884 to 1918, the German colonial government and its representatives perpetrated genocide against the indigenous Nama and Herero peoples while scouring the region for diamonds. According to Press, Germany’s ambition reshaped the global diamond market and continues to do so today.

“While exploring what was going on in these German colonies, I saw an economic dimension and also a worldwide thread that hadn’t been appreciated,” said Press, an assistant professor of history in the School of Humanities and Sciences. “Following the path of diamonds showed important connections to economic life in Europe and the United States, not to mention Africa, and that dynamic hadn’t really been examined.”

While German colonialism has been studied extensively before, it was generally thought to be an economic failure for the country, which left many scholars and politicians wondering why the German government kept pouring resources into its Southwest African colony. What Press found, however, is that German colonial diamonds provided more economic gain than had previously been recognized.

Colonial latecomers

Lasting roughly from 1884 to the end of World War I in 1918, the German overseas empire had its signature holding in Southwest Africa, known today as Namibia. The colony was beset by mismanagement and a brutal military campaign that killed tens of thousands of Indigenous people, many of whom perished in concentration camps.

Germany discovered diamonds in Namibia in 1908 but was searching for them prior to, and throughout, its genocidal activities there. Press paints a dark picture of a forbidding and unforgiving desert area called The Zone, the colony’s richest diamond source. African migrant workers lost their lives mining in The Zone’s harsh, dangerous conditions, all of which were rendered deadlier by European greed and violence.

Germany was late to the colonial stage, behind rivals France and Britain. But noting that Germany was a powerful scientific and industrial nation, Press said he sought answers about the country’s perceived economic underperformance in Southwest Africa. What he found was a deliberate undercounting in terms of revenue produced by the German colony and new revelations about the ways the Germans capitalized on the burgeoning U.S. diamond market.

The reason for their undercounting, Press said, was to enrich a few colonial companies and German elites at the expense of the German people. Most Germans, let alone Namibians, never felt the impact of the extraordinary wealth obtained from colonial diamonds.

Diamond scarcity

The British had come into the diamond market ahead of the Germans and had constructed a false narrative about diamond scarcity, thus creating more demand. Stepping into this British-dominated market was a strategic move for Germany.

“That gave them a potential weapon against the British Empire, economically speaking,” Press said. “By being able to flood the market with their own diamonds, the Germans gained leverage.”

The Germans made strategic alliances with the diamond cutters of Antwerp and took advantage of the consumer appetites of Americans, who embraced mass-marketed diamond engagement rings. “By 1908, the United States accounted for 75 percent of world diamond demand, followed distantly by Britain, Germany and France,” Press writes. “Americans became consumers of ‘blood’ or ‘conflict’ diamonds, well before such concepts existed.”

Then as now, the diamond business was largely a secretive one. A lot of value was obscured and hidden, which made it difficult for Press to find both historical and current information on it. He examined archives around the world – from the U.S. to Southern Africa to Europe – to piece together and triangulate numbers from the U.S. market to reconstruct the value chain.

For example, Press found that after the extraction of rough diamonds in Namibia, the price of an average diamond increased by 20 times. Such inflation started in Berlin, where a consortium of bankers slapped major markups on diamonds in exchange for the easy work of forwarding them to Antwerp for cutting. In Antwerp, cut diamonds doubled in price and were shipped out to the United States. After dealing with importers, American jewelers finally sold diamonds to consumers after another price increase of 50 percent.

“By the time these diamonds ended up on someone’s finger as an engagement ring, their price had risen in an extraordinary way,” Press said.

Blood and diamonds

The title of Press’s book, Blood and Diamonds, is a nod to the idea of conflict minerals, or resources obtained at the cost of human life. In recent years, much of the world has used the term “blood diamonds” to describe diamonds extracted from war zones in places like the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

The reality of the German colony in Namibia is of importance today as Europeans and Africans struggle with the aftermath of colonialism in terms of reparations and ongoing legacies, Press said.

While today’s consumers can be more selective about where their diamonds are sourced or choose not to buy them at all, Press asks what Americans should or will choose to do with all those diamond engagement rings accumulated over decades of European colonial rule. The stones will continue to sparkle despite the darkness of their legacy.

“It’s important to have a discussion about conflict commodities,” Press said. “We want to buy things we feel good about, but what do we do with conflict resources we’ve had for 50 or 100 years? The stain of the blood, so to speak, never really goes away.”