How the Biden administration can help to slow damage and build resilience in a rapidly changing Arctic

Stanford University scholars discuss the Biden administration’s early actions on environmental issues in the Arctic and how the U.S. government can address threats to ecosystems, people and infrastructure in the fastest-warming place on Earth.

“A climate in crisis,” President Biden said in his inauguration speech, is among a cascade of challenges in a “winter of peril and possibility.”

An iceberg melts in Kangerlussuaq Fjord, Greenland. Warm fjord waters melting the iceberg underwater produce a rounded and smooth texture. The iceberg extends about 160 feet above the surface of the fjord. The circle of slush surrounding the berg demonstrates how rapidly the berg is eroding. (Image credit: Rob Dunbar)

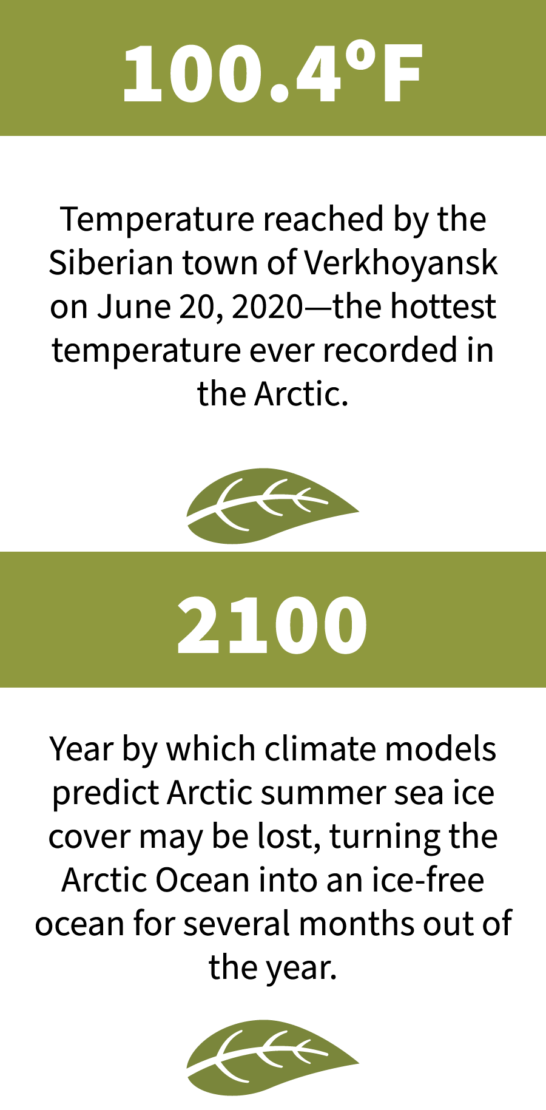

Few places face more urgent threats from climate change than the Arctic, which is warming more than twice as fast as anywhere else on Earth. Sea ice has radically declined since the 1970s. Within a few decades, summer sea ice may disappear completely – with implications for regional weather patterns, erosion, shipping traffic and oil exploration, as well as extreme weather events and sea-level rise in the U.S. and around the world.

Rapid environmental changes add to challenges facing the Arctic’s more than 4 million residents, roughly 1 in 10 of whom are part of Indigenous groups who have long relied on sea ice and marine ecosystems.

According to Stanford University scholars, the Biden administration can help to slow damage and lay groundwork for a more sustainable future for Arctic ecosystems and inhabitants. Actions they see as key include slashing carbon emissions; hitting the brakes on oil development in sensitive coastal areas; repairing relationships with other Arctic countries; improving fisheries management; and providing resources for Arctic communities to relocate from places becoming unlivable due to global warming.

“Given the speed of change in the Arctic, the sooner that environmental policies are implemented, the more effective they are likely to be,” said Kevin Arrigo, professor of Earth system science.

Executive orders

On his first day in office, President Biden committed the country to rejoin the Paris Agreement, the 2015 international accord designed to avert catastrophic climate change. He ordered a moratorium on oil and gas leasing in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge (ANWR) and a review of the potential environmental impacts of the long-debated oil and gas program in the coastal refuge. He also reinstated Obama-era protections for a “climate resilience area” off the coast of Alaska, withdrawing certain offshore waters and the Bering Sea from oil and gas drilling.

Sea ice surrounds the U.S. National Science Foundation Polar Research Vessel Nathaniel B. Palmer, which has supported Stanford science teams in the Arctic and Antarctic since 1995. (Image credit: Rob Dunbar)

Stanford oceanographer Rob Dunbar said he favors halting oil activity in ANWR, where the Trump administration approved leases for drilling on its last full day in office – nearly four years after Congress opened a 1.5 million-acre section of the refuge to oil development.

“We do not need the oil and gas that is in ANWR to keep our country going as we transition to green energy,” Dunbar said. “It is expensive and environmentally dangerous to explore for and produce hydrocarbons in the far north, and it seems nuts to do so while we are trying to develop, fund and implement the non-fossil energy systems that we need to quickly bring online.”

For animal populations in the Arctic, recent research led by Arrigo suggests climate-related stresses have a greater impact than do acute stressors such as increased shipping and subsistence harvesting. “The biggest concern in the short term is the loss of sea ice,” Arrigo said. Longer term, the Arctic Ocean’s relatively shallow waters and the importance of shelled marine animals in its food web heighten its vulnerability to acidification, which occurs when seawater absorbs more carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. “The only policy intervention I can think of to address these issues is to reduce CO2 emissions,” Arrigo said.

The new administration’s return to the Paris Agreement and framing of climate change as an “existential threat” central to U.S. domestic, national security and foreign policy may aid cooperation among Arctic nations on emissions and other climate issues.

“The United States was in effect blocking much of that work for four years,” said David Balton, a senior fellow at Stanford’s Center for Ocean Solutions and a former U.S. ambassador who was in charge of Arctic policy until 2017. “President Biden’s decision to bring us back into the Paris Agreement had immediate effects on the perception of the United States among the other Arctic governments and on their willingness to deal with us.”

Resilience and adaptation

Reinstatement of the resilience area in the Bering Sea carries “huge” significance, Dunbar said. “It sends a message to the Indigenous inhabitants of the region that we as a nation do care about their plight.”

By prohibiting bottom fish trawling and limiting shipping and oil and gas development, the arrangement protects a highly productive ecosystem, including iconic species such as whales and polar bears. While these protections cannot fully mitigate the effects of climate change, he said, dealing with local stressors can buy time. For example, better fisheries management can help prevent stock collapses even as warming oceans and streams cause some fish populations to decline, he said.

At the regional level, securing commitments to rein in soot pollution could have “strong and fairly quick consequences” for slowing Arctic warming, Balton said. When the dark particles settle onto ice and snow, reflectivity is lowered, so more of the sun’s heat ends up being absorbed.

According to Balton, the central Arctic Ocean notably lacks an international marine science organization of the sort that has helped to spur science efforts in the North Atlantic and North Pacific regions. “That might be a good first step to build confidence and strengthen international institutions for the region,” he said.

Kristen Green, a Stanford PhD student whose research focuses on sustainable marine resource planning for Alaskan Arctic communities, hopes to see the Biden administration bring new urgency to climate adaptation. “This issue will affect every aspect of Arctic decision-making, from an international to village scale,” she said.

The Coastal Climate Resilience program, proposed by President Obama but never enacted, offers a promising model, Green said. The program would have provided funding to relocate entire Alaska Native villages threatened by the effects of climate change, and offered resources for at-risk coastal states, local governments and their communities to prepare for and adapt to climate change.

“There are huge economic costs to a warming Arctic Alaska,” she said. These are not distant threats: “The wild foods that Alaska Natives have relied on since time immemorial are becoming harder to access,” she said. And already, thawing of the permafrost that underlies homes, pipelines, railroads, military bases and other infrastructure throughout much of the Arctic has caused cracks, buckles and spills. According to Green, “The rest of the world will be looking to Arctic communities for lessons in adaptation and resilience in the face of climate change, and the United States can be a leader here.”

Kevin Arrigo is the Donald and Donald M. Steel Professor in Stanford’s School of Earth, Energy & Environmental Sciences (Stanford Earth). Rob Dunbar is the W.M. Keck Professor at Stanford Earth and a senior fellow at Stanford’s Woods Institute for the Environment. Kristen Green is a PhD student in the Emmett Interdisciplinary Program in Environment and Resources (E-IPER). David Balton is affiliated with the Wilson Center’s Polar Institute in Washington, D.C.

To read all stories about Stanford science, subscribe to the biweekly Stanford Science Digest.