To instruct, entertain and persuade: political art at the Cantor

Stanford curator explains the history of art and politics in the context of current affairs.

As the 2020 presidential election approaches, artists across the nation – including Deborah Kass, Richard Serra, Stephanie Syjuco, Carrie Mae Weems and others represented in the Cantor Arts Center’s permanent collection – are creating new works to protest, comment on U.S. politics and inspire people to vote.

Elizabeth Kathleen Mitchell, the Burton and Deedee McMurtry Curator and Director of the Curatorial Fellowship Program at the Cantor Arts Center. (Image credit: Courtesy Cantor Arts Center.)

“I think all of us right now are grappling with how to both be responsive and active in the world at this moment – whether it’s in the streets or whether it’s in our communities or outside our spaces of comfort,” Syjuco, MFA ’05, said this summer in a virtual artist talk with Susan Dackerman, the John and Jill Freidenrich Director of the Cantor Arts Center.

For some, that means designing art to be worn at rallies and marches. Others are optimizing works for digital consumption by formatting images and reproduction rights to facilitate social media sharing. Although mediums and messages have evolved alongside the zeitgeist, the history of art and politics is vast.

In this Q&A, Elizabeth Kathleen Mitchell, Cantor’s Burton and Deedee McMurtry Curator and the director of the Curatorial Fellowship Program, talks about the relationship between art and politics and previews opportunities at the museum to engage with art that addresses conflict, power and governance while prompting dialogue about artists’ enduring calls for social justice.

What is the relationship between art and politics?

Art and politics became intertwined as soon as humans realized that images could instruct, entertain and persuade. I explore this fascinating and complex relationship throughout the upcoming exhibition Paper Chase: Ten Years of Collecting Prints, Drawings, and Photographs at the Cantor, which will be presented at the Cantor in 2021. Nearly every work in the exhibition has a political undercurrent – even omission and distortion are powerful tools in visual culture.

Not only is meaning invested in the design, but an artist’s choice of materials, processes and sites of production can speak volumes. For instance, Paper Chase will feature an impression of the 1770 “Boston Massacre” engraving, the famous image of British soldiers shooting American colonists, that fueled support for the American Revolution. Our print comes from an edition that was published and sold in London. Knowing that printers in England dared to produce such a politically explosive image adds another layer of information to our understanding of its history.

Given your role curating works on paper, can you speak specifically to the rich history of political posters in the U.S. and globally?

For centuries, posters and prints have been vehicles for the visual representation of identities, beliefs and social issues with the intention of motivating social and cultural change. Printed propaganda has long played an essential role in spreading information in times of war, political action or during quests for social justice. Artists traditionally created political posters and prints from cheap materials, knowing the objects would be stuck onto city walls and papered over, torn down or destroyed by weather. The Cantor has a significant representation of American, French and Russian war posters, as well as the “fine art” prints that responded to those same moments. An example of the latter is José Clemente Orozco’s 1935 lithograph The Masses, another print that will feature in Paper Chase. It depicts a politician’s nightmare. Orozco shows us a furious mob of figures with grasping hands, oversized mouths and bulging bellies; they are worked up into a furor because they lack brains, and a clear cause, to guide them.

Image credit: ©Stephanie Syjuco; Courtesy of the artist and RYAN LEE Gallery, New York

Zapatello is a mixed media sculpture from composer and performer Guillermo Galindo created for his series Border Cantos, an exploration of the U.S.-Mexico border. It will be included in the upcoming Cantor exhibition When Home Won’t Let You Stay: Migration through Contemporary Art.

Pakistani-American artist Ambreen Butt’s work addresses topics of fear, violence, free speech, beauty, strength and power. Her 2008 piece Untitled, part of a five-part series, responds to the 2007 siege of Lal Masjid, or Red Mosque, in which women were used as shields when the complex was raided by the Pakistani government. The work will be featured in the postponed exhibition Paper Chase: Ten Years of Collecting Prints, Drawings and Photographs at the Cantor.

Image credit: Palmer Gross Ducommun Fund, 2011.38.5

Canvassing for Votes is from the set of four related engravings Four Prints of an Election based loosely on the Oxfordshire election of 1754. It aims to unveil political corruption, covertly accepted bribes, coercion and mob attacks.

Image credit: Fenton Family Fund, 2019.51.3.1

Image credit: Elizabeth and Leonard Offield Art Fund, 2019.196

Kallat’s Woven Chronicle redraws a map of the world crisscrossed by migratory paths and transportation lines constructed from barbed wire, portending both danger and continuity. Within the map are speakers that contain an audio component and echoes the movement of people, goods and animals across borders defined and otherwise. The work will be included in the upcoming Cantor exhibition When Home Won’t Let You Stay: Migration through Contemporary Art.

Image credit: © Reena Saini Kallat. Courtesy the artist and Nature Morte, New Delhi. Installation view, Insecurities: Tracing Displacement and Shelter, The Museum of Modern Art, New York, 2016–17. Photograph by Jonathan Muzikar. Digital image © The Museum of Modern Art/Licensed by SCALA/Art Resource, NY

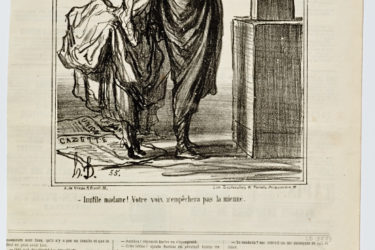

Prolific French printmaker, painter, sculptor and caricaturist Honoré Daumier frequently offered comment on the social life of France in the 19th century and criticism of the monarchy. Over 40 years, he contributed nearly 4,000 lithographs and hundreds of wood engravings to daily publication including Le Charivari, which offered political critique and satires of everyday life.

A close look at Wesaam Al-Badry’s photograph of a Muslim woman in a traditional niqab reveals a deeper level of symbolism: the veil is made of designer silk and decorated with symbols of independence. His work Hermes #V will be featured in the postponed exhibition Paper Chase: Ten Years of Collecting Prints, Drawings and Photographs at the Cantor.

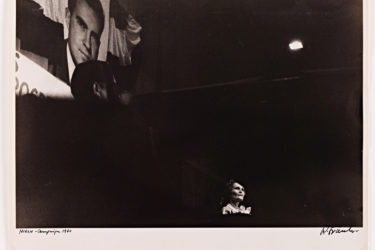

Influential documentary photographer Robert Frank chronicled American life through black-and-white images. His 1959 book, The Americans, was, according to the Washington Post, a “group portrait of the nation, honest and stark and not always flattering.”

Painter, printmaker and cartoonist Don Freeman considered Honoré Daumier to be one of his greatest influences. Though his subjects included political figures and daily life in New York City during and after the Great Depression and Second World War, he is perhaps best known for his publication of the children’s book Corduroy. Here he depicts the wartime President Roosevelt, victorious after taking a “bruising” during the 1940 election, which made him the only U.S. president to serve a third term.

As curator Elizabeth Mitchell describes, “Orozco shows us a furious mob of figures with grasping hands, oversized mouths and bulging bellies; they are worked up into a furor because they lack brains, and a clear cause, to guide them.” The work will be included in the postponed exhibition Paper Chase: Ten Years of Collecting Prints, Drawings and Photographs at the Cantor.

What examples from the Cantor’s collection would you highlight that explicitly addresses political contexts?

In 2021 we also will be presenting an exhibition I curated titled A Loaded Camera: Gordon Parks which features highlights from The Capital Group Foundation’s recent gift to the Cantor of a body of exceptional Parks photographs exploring Black life during the American civil rights era. Paper Chase will feature many other new acquisitions concerned with how different people express personal identity and autonomy, negotiate social power structures and relate to the environment. Among those are Boston photographer Jess Dugan’s portraits of aging trans and non-binary identifying adults and Carrie Mae Weems’ landmark 1997 photographic series Not Manet’s Type, which questions the place of women and artists of color in the art historical canon. Another great inclusion is the fantastic 2009 lithograph by Stanford faculty member Enrique Chagoya titled Illegal Alien’s Guide to the Concept of Relative Surplus Value, which confronts institutionalized racism, immigration and climate change.

How have these resources been utilized for scholarship at Stanford?

Changing exhibitions like Paper Chase, the permanent collection installations, and our public programs often address art’s political underpinnings. We invite curatorial staff, scholars, students and artists to discuss complex works of art, making the museum a forum for relevant political conversations.

Students who participate in our scholarly research programs also use the collection to investigate thorny historic issues in exhibitions and publications. However, the most focused and intensive use happens in our study rooms. Faculty also bring students in to directly experience the iconography and physicality of objects and to conduct research with museum staff. Now that access to campus is limited and these encounters must happen online, we are developing new digital teaching resources to feature the collection and make it accessible in new ways.

Performance artist Tania Bruguera, who spoke at Stanford in 2016, issued a statement saying “Political art is the one transcending the field of art, entering the daily nature of people, an art that makes them think … Political art has doubts, not certainties; it has intentions, not programs; it shares with those who find it, not imposes on them; … Political art is uncomfortable knowledge.” What can these works teach us about “uncomfortable knowledge” and how it might encourage the viewer to reframe her or his values?

When we open ourselves up to experiencing new art, we also must accept the possibility of becoming very uncomfortable – and having to dissect that discomfort. Art has the power to make us temporarily set aside our assumptions and everyday distractions in order to look, listen and contemplate how other people experience the world. This kind of thinking pushes us to decide who we are and what we stand for. It connects us with others across time and national boundaries, and the experience can be transformative.

How are artists and political art responding to this moment?

This is a fascinating moment for artists, which makes in all the more exciting for museum professionals. As the conversation of the moment is shaped by urgent local issues and critical global problems, so many kinds of art experiences and conversations about art have shifted to happen online. What interests me is what will happen when we can begin to have these experiences together in person – and in front of the art objects – again.