“Without the death of Leland Stanford Jr., you don’t have the museum and you don’t have Stanford University.”

—Mark Dion

2019-20 Diekman Contemporary Commissions Program Artist

When Jane and Leland Stanford experienced the immense pain of losing their only son, Leland Jr., just before his 16th birthday, they were compelled to enshrine his memory in a meaningful way. The resulting museum and university they founded not only secured young Leland’s place in history – artist Mark Dion argues that this particular death changed the world. Dion’s exhibition, The Melancholy Museum: Love, Death, and Mourning at Stanford, opens at the Cantor Arts Center Sept. 18.

“Without the death of Leland Stanford Jr., you don’t have the museum and you don’t have Stanford University,” Dion explained. “Without Stanford University, you probably don’t have the Silicon Valley. Without the Silicon Valley, there are a number of things that we certainly don’t have in the way that they look today, including personal computers, and phones and the internet. So, the death of a child set off a chain reaction that dramatically shaped the course of the information future of the world.”

Go to the web site to view the video.

Curiosity

At Stanford University’s 2019 Commencement ceremony, Stanford President Marc Tessier-Lavigne remarked on visiting the Cantor and reading the young Leland Jr.’s journals: “What truly leaps from the pages is Leland Junior’s extraordinary curiosity.”

It is this broad curiosity that is highlighted in the Cantor’s new exhibition, with numerous examples of things that fascinated the 19th-century child, like a toy cannon and a coin trapped in lava. Although these vernacular objects are not things one might normally expect to see in an art museum, these objects were chosen by Dion to help tell the Stanford story.

“I see the museum as a space where one obtains knowledge through an encounter with things,” the artist explained. “I think of the museum as the place that generates wonder, which leads to curiosity, that results in knowledge. The best museums start a chain reaction in visitors, but the catalyst for this reaction is the object or collection itself.”

To give Cantor visitors that transformative experience with objects, Dion created an interactive Victorian mourning cabinet to display myriad items from the family, including beautiful ones like a jade bird and a beaded necklace; unusual items, like cannonballs and a piece of the Roman Colosseum; as well as items that reflect the young Leland’s interests such as toys, antiquities and natural history specimens. The display is organized according to the five classical elements: air, earth, ether, fire and water, which were used by the artist as a way to place disparate elements into cohesive groupings and to reflect ancient times when the elements provided a way to create order in an often-unpredictable world.

Visitors to the exhibition will be able to open over 50 drawers that are included in the display cases and in the mourning cabinet, a creation of Dion’s that is reflective of the curiosity cabinets of the Renaissance era, where collections were often displayed.

Interactive Victorian mourning cabinet created for the exhibition. (Image credit: L.A. Cicero)

Expanding narratives

While the original Stanford Family Galleries focused almost exclusively on the story of the Stanfords themselves, Dion has broadened the narrative in this exhibition using archival documents and found memorabilia from the laborers who built the railroads – some of whom later labored on the Stanford family’s many estates and helped them amass their wealth. Leland Stanford Sr. was president of the Central Pacific Railroad, which employed many Chinese laborers who worked in perilous conditions to construct a railroad through the difficult terrain of the Western United States. The Last Spike, used by Stanford Sr. at Promontory Summit, Utah, to connect the two halves of the intercontinental railroad 150 years ago, is part of the exhibition.

Alfred A. Hart (U.S.A., 1816-1908), The Last Rail is Laid scene at Promontory Point, May 10, 1869. Photograph. (Image credit: Department of Special Collections, Stanford Libraries)

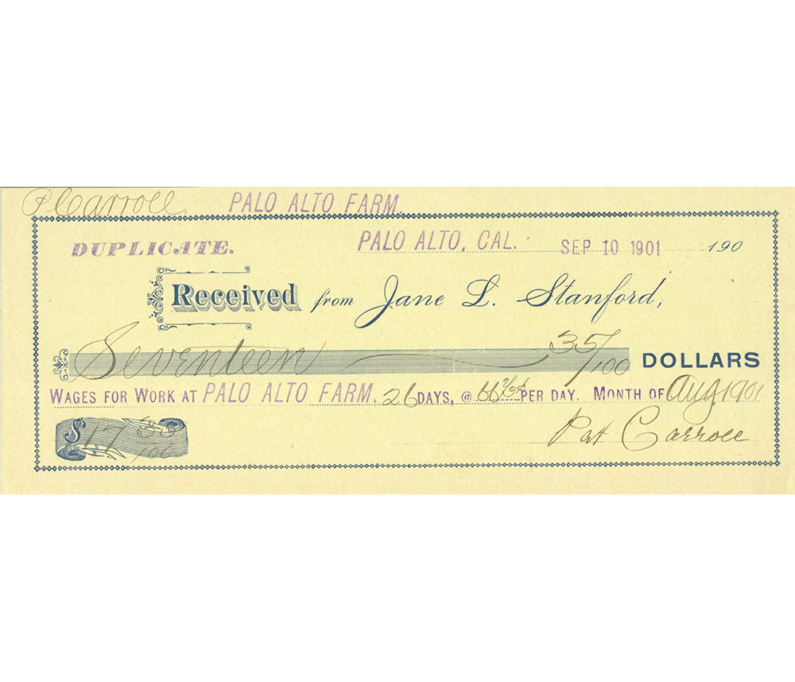

Artist unknown, Check Receipt, 1901. (Image credit: Department of Special Collections, Stanford Libraries)

Also on view are objects from the native Ohlone people on whose ancestral land the university now stands. An essay in the Field Guide that accompanies the exhibition explains the deep connection between the university, the museum and the Ohlone people. In 1988, Stanford repatriated human remains and funerary objects that had been stored in the basement of the museum to the Ohlone for reburial. The university and tribe now cooperate in many ways including community-led archeology, historic interpretation and a native plant garden.

Other areas explored in the new exhibition include the two earthquakes in 1906 and 1989 that destroyed large parts of the historic museum; the afterlife; and photography, a passion of young Leland Jr.’s.

Student involvement

Throughout his more than a year on campus, reviewing over 6,000 items in the Stanford Family Collections, Dion has had the opportunity to work with students to explain his practice and provide insights into his process. Student guides, undergraduate and graduate students who receive a year of training and then lead tours at both the Cantor and Anderson Collection at Stanford, had the opportunity to learn from Dion as did students in the course Wonder, Curiosity & Collecting: Building a Stanford Cabinet of Curiosities taught by Dackerman and Paula Findlen, professor of early modern Europe and the history of science in Stanford’s Department of History. The undergraduate and graduate students in the winter quarter course had the opportunity to examine objects with Dion and to contribute essays about select objects to the Field Guide that accompanies the exhibition. Another key student contributor to the project was Anna Toledano, a PhD candidate in the History of Science, who authored the Field Guide chapter about the earthquakes that struck the museum.

Ben Maldonado, ’20, one of three undergraduate students to participate in the Stanford Family Interpretive Project. (Image credit: George Philip LeBourdais)

In conjunction with the Melancholy Museum exhibition, George Philip LeBourdais, who received his PhD in 2018 from Stanford’s Department of Art and Art History, worked with three undergraduate students in the Stanford Family Interpretive Project to create interactive media projects that reveal hidden stories and forgotten peoples through close examinations of artifacts in the Stanford Family Collections. These include 19th-century watercolor paintings of the California missions by Henry Chapman Ford, Asian antiquities and Native American objects.

In collaboration with the Cantor staff and under the direction of staff and faculty at the Center for Spatial and Textual Analysis, the students produced “story maps,” interpretive historical essays woven together with images and interactive maps, in order to trace the complex histories of objects and the people that made them.

Ben Maldonado, ’20

Maldonado’s project focuses on artist Henry Chapman Ford’s watercolor depictions of the Spanish missions that were established in California.

Cathy Yang, ’20

Yang’s project focuses on the over 300 Asian artworks – including bronzes, jade and ivory pendants and ink paintings – in the Stanford family’s collection.

Roshii Montano, ’20

Montano’s project focuses on the Stanford family’s collection of Native American objects, much of which was amassed in the 1880s and 1890s.