NBA legend Kareem Abdul-Jabbar visits Stanford

In a discussion Wednesday at Memorial Auditorium, Kareem Abdul-Jabbar discussed the intersections of race, religion and politics.

Kareem Abdul-Jabbar’s accomplishments on the basketball court have made him a sports legend and a cultural icon. As the National Basketball Association’s all-time leading scorer and a six-time league champion, he remains best known for his contributions to the sport. However, he insists there’s much more to him than basketball.

“I love the game, but it’s not my only love,” he said before a sold-out crowd at Memorial Auditorium Wednesday evening.

Hakeem Jefferson, assistant professor of political science, and Alaina Morgan, a postdoctoral fellow in the Department of Religious Studies, interview retired NBA star Kareem Abdul-Jabbar at Memorial Auditorium on Wednesday, May 1, 2019. (Image credit: Rod Searcey)

In a discussion with religious studies postdoctoral fellow Alaina Morgan and Assistant Professor of Political Science Hakeem Jefferson, Abdul-Jabbar discussed his many interests off the court – politics, race relations and religion, all of which he explores in his book Writings on the Wall: Searching for a New Equality Beyond Black and White.

The event was sponsored by the Abbasi Program in Islamic Studies, the Stanford Global Studies Division and the Department of Religious Studies. It was part of a series called “Islam in America,” which highlights the diverse experiences of Muslims in the United States.

A native of New York, Abdul-Jabbar was raised Roman Catholic but converted to Islam in 1968. That was the year he boycotted the summer Olympics by forgoing a chance to try out for the men’s national basketball team. His reason, he said, was the racial violence occurring in the country, including the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

“It didn’t make sense to me that we would go to Olympics,” he said. “I wasn’t feeling very patriotic.”

At the time he was a junior at the University of California, Los Angeles, playing for legendary coach John Wooden. In the classroom, he was studying history, which he has called the ultimate self-help book. Reflecting on America’s own history of racism and violence, Abdul-Jabbar said the country still has a long way to go before reaching full equality. When asked about political polarization and the current state of American democracy, he urged those who are losing trust in the process to be patient.

“The process takes time. It doesn’t work fast,” he said, adding that demographic changes in the country mean our political system will need to be more inclusive in order for civility to be maintained.

“The reins of power now have to be shared with those who are not white,” he said. “There’s only one planet so we have to find a way to get along.”

Outside of basketball, Abdul-Jabbar has made a name for himself through other platforms. He’s made numerous film and television appearances, including his film debut in Bruce Lee’s 1972 film Game of Death and a memorable role in Airplane in 1980. He’s also become a prolific writer, authoring 14 books and contributing articles about

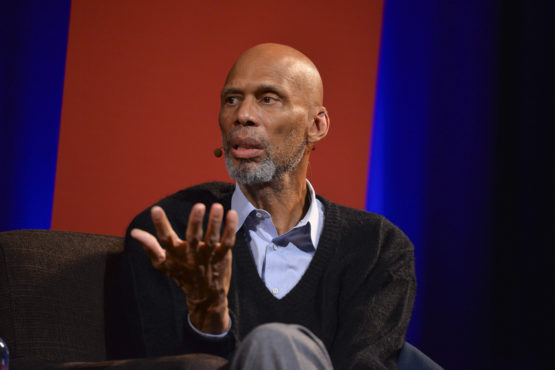

Retired NBA star Kareem Abdul-Jabbar discusses politics, race and religion at Memorial Auditorium on Wednesday, May 1, 2019. (Image credit: Rod Searcey)

politics and social issues for publications like The Guardian and the Hollywood Reporter.

Addressing the pressure many athletes and entertainers have to avoid activism and stick to performing, Abdul-Jabbar insisted everyone has a right to get involved in the political process and express their views.

“The fact that someone is an athlete does not remove their right to speak out,” he said.

During the 90-minute talk, Abdul-Jabbar also discussed his love of fiction and the art of storytelling. He said he loves detective novels and recommends IQ, the debut novel from author Joe Ide. When the conversation inevitably turned to the NBA playoffs, he said he had no idea who would win the finals, but added, “the Boston Celtics and Milwaukee Bucks are looking tough this year.”

During a question-and-answer session with the audience, Abdul-Jabbar also discussed mass shootings, newly elected congresswoman Ilhan Omar and how he was influenced by such activists as Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X, who was also a prominent American Muslim.

When asked about the modern role of religion in a country that seems to be growing more secular by the day, he maintained its importance. “I think religion still serves a great purpose in defining morality,” he said. “I’m glad I had Islam to teach my kids the difference between right and wrong.”