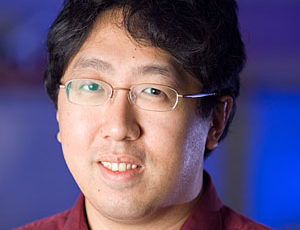

Stanford’s Robot Makers: Andrew Ng

Andrew Ng is an adjunct professor of computer science at Stanford University. In his first decade at Stanford, he worked on autonomous helicopters and the STAIR project. He is now focusing on applications for artificial intelligence in many areas, including health care, education and manufacturing. This Q&A is one of five featuring Stanford faculty who work on robots as part of the project Stanford’s Robotics Legacy.

What inspired you to take an interest in robots?

I’ve always played with robots. For example, I remember a competition in high school where my friends and I built a robotic arm to move the chess pieces on the chessboard. It seems very trivial now, but way back then, the robots were all primitive and as high school students, we thought that building a robot that could do that was a big deal.

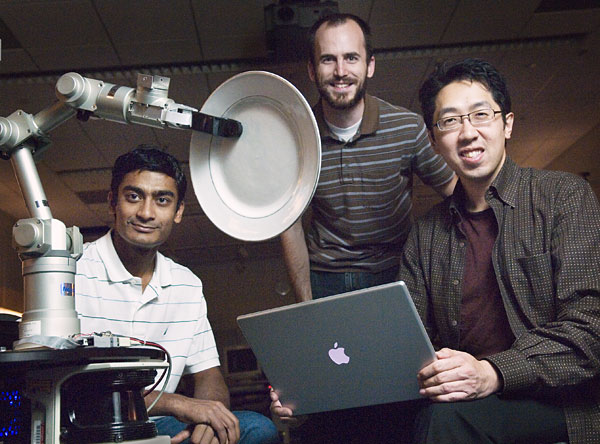

Graduate students Ashutosh Saxena, left, and Morgan Quigley, center, and Ng were part of a large effort to develop a robot to see an unfamiliar object and ascertain the best spot to grasp it. (Image credit: L.A. Cicero)

Today, I regularly see high school students do the stuff that would have won the best paper award at an academic conference if someone had done it 10 years ago. So our field is evolving a lot.

What was your first robotics project?

During my PhD thesis at UC Berkeley, I remember asking a bunch of people what were the hardest problems in robotics. Some of my friends suggested flying helicopters, so I wound up with a PhD thesis involving autonomous helicopter flight. Then, a couple of my earliest PhD students at Stanford, Pieter Abbeel and Adam Coates, did a phenomenal job of taking that to the next, next, next level, until, frankly, we ran out of things to do on autonomous helicopter flights. They did it so well, we had to shut the research down.

Afterward, I began working on machine learning and computer vision and perception. People were working on different subsets of the AI problem and I thought having a project called STAIR – the STanford AI Robot – would help synthesize multiple facets of AI faculty together. It was a generalized robot, very much inspired by Shakey [the first artificially intelligent robot].

I think one of the biggest things to come out of STAIR was a project called ROS (Robot Operating System). Today, if you go to pretty much any university that works with robotics they are using ROS. ROS has literally made it off our planet and is now running on a robot that’s been on the International Space Station. Plus, it’s maintained by a 20-person nonprofit called the Open Source Robotics Foundation, which was co-founded by one of my PhD students, Morgan Quigley.

Talking about all of this, I’m just a professor. Honestly, much of the work was done by the PhD students who are the real heroes behind this work.

Thinking back, what did you hope robots would be doing in the “future”?

When I was in high school, I did an internship. I was the office assistant’s assistant and I did lots of photocopying. I remember thinking that if only I could automate all of the photocopying I was doing, maybe I could spend my time doing something else. That was one source of motivation for me to figure out how to automate a lot of the more repetitive tasks.

At the STAN (Society, Technology, Art and Nature) event in 2011, Ng spoke about his work with autonomous helicopters. (Image credit: L.A. Cicero)

Even today, I think artificial intelligence is very poorly understood. The main power of AI today is not about building sentient robots. It’s automation on steroids.

One of the unfortunate things is there is artificial general intelligence and artificial specialized intelligence. Almost all the recent projects are having AI to do specialized tasks. It’s general intelligence that makes people picture the evil, killer robots that might enslave us all. It might be hundreds of years or thousands of years before AI might have general intelligence but none of us even see a clear shot to figure that out.

What are you working on now related to robotics?

My PhD background in robotics was really a control project – controls being the way you get robots to perform a specific task. But STAIR was where we realized perception was a more pressing problem. The perception problem is how robots interact with the environment around them, how they accurately sense the world and tell us, “Where is the person, where is the door handle, where is the stapler.”

A very special piece of work, done by my PhD student Ashutosh Saxena, was to get the robot to pick up objects it had never seen before. It was pretty controversial when he did it but now everyone in robotics thinks it’s the way to go. That’s when I had my research group start to spend most of its time on deep learning because that was the best way to solve a lot of the open perception problems.

At some point, hopefully, we’ll tie that back to robots but we’re not focused on that right now. The living incarnations of STAIR are alive and well. A lot of the early ideas we had about how robots should grasp an everyday object, those ideas have been crucial to the research.

How have the big-picture goals or trends of robotics changed in the time that you’ve been in this field?

The rise of deep learning has created a sea change over the last five years because deep learning has made it so robots can see much more clearly. There have been advances in other areas as well – more controls work, mechanical engineering, the materials work. There are perception solutions that work way better compared to five years ago. This has created a lot of opportunities in robotics applications.

As for the general purpose robot, like Shakey and STAIR, those are very research-focused. Research will continue to try to build general robots because that drives a program to explore basic science questions. In terms of the robots that are likely to make it into our lives in the near future, I think those will be specialized robots. For example, one of my students has a robot that was recently purchased for specialized agriculture.