Proscriptions and prescriptions for the next wave of cleantech investments, new Stanford-led analysis finds

The boom and bust in clean energy investments starting in 2008 produced some lessons to guide future government policy and investment strategies for the next cycle of investment in a sustainable energy future.

A U.S. investment boom in clean energy technology could go better the second time around with guidance from an analysis led by Stanford University experts of what went right and wrong the first time.

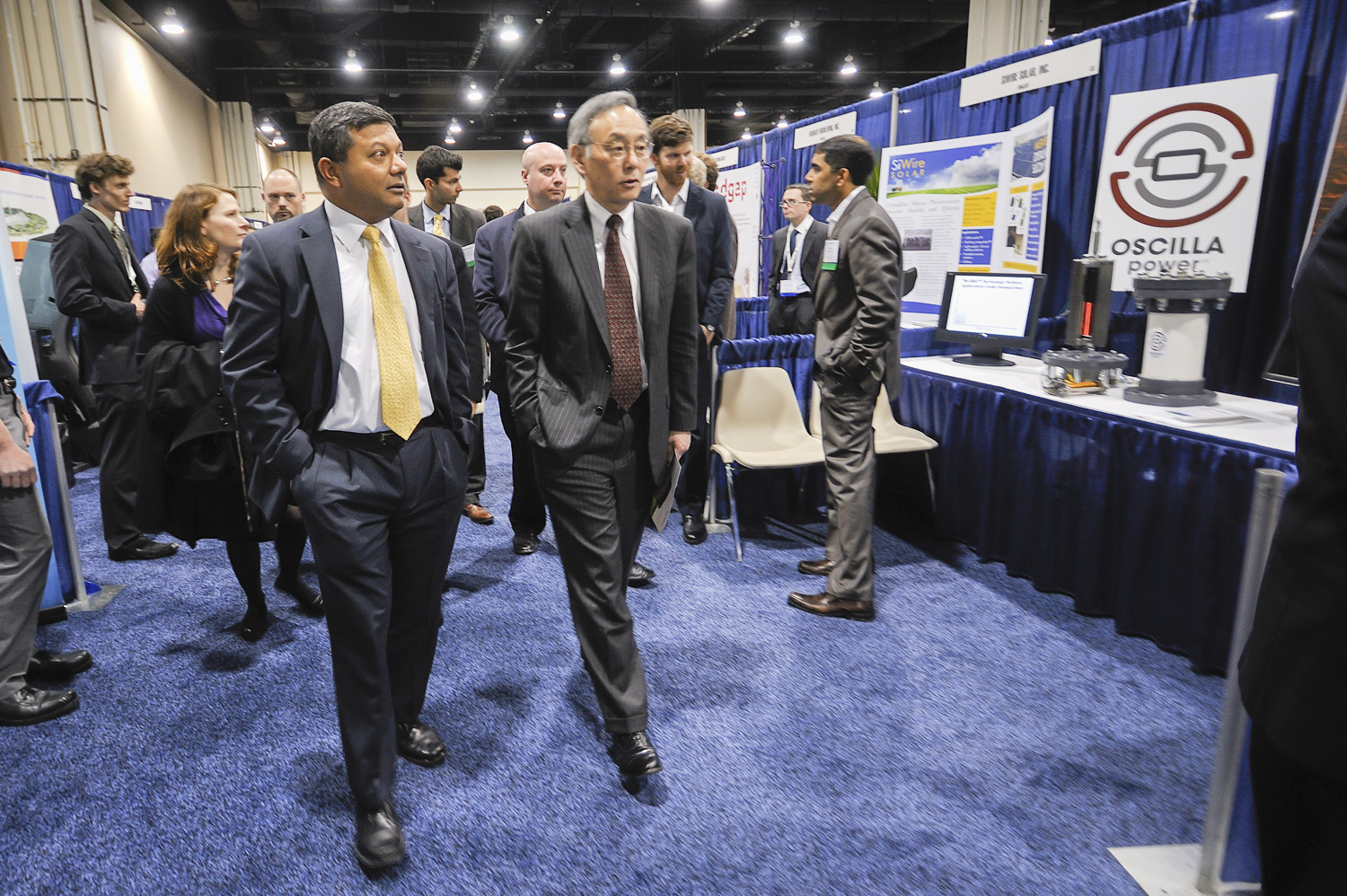

Former U.S. Secretary of Energy Steven Chu, right, and Arun Majumdar, former director of the Department of Energy’s Advanced Research Projects Agency-Energy, tour the agency’s Energy Innovation Summit in 2011. Now both members of the Stanford faculty, Chu and Majumdar are two of 11 experts interviewed for a new analysis of how the next boom in cleantech investments can be more productive than the first one. (Image credit: Ken Shipp / DOE)

Venture capital investments in clean energy – or cleantech – startups peaked in 2008 and have been mired in a slump the past six years, despite a 10-year bull market for almost all other U.S. investment sectors. When funds dried up, a generation of companies merged, shut down or sold cheaply. The lessons learned from that cycle by investors, government policymakers and entrepreneurs will help when cleantech investing rebounds, according to the researchers.

“The next cycle will be much more productive,” said Stanford professor of management science and engineering John Weyant, who co-authored a new book outlining the findings. “It has to be. The prerequisites for making the world’s energy sustainable, affordable and reliable is technological innovation and rapid deployment of the fruit of those efforts.”

Weyant and the co-authors of Renewed Energy: Insights for Clean Energy’s Future drew their conclusions from in-depth interviews of 11 thought leaders in the energy sector, including John Woolard, who led startups Silicon Energy and BrightSource Energy; Tom Baruch, the founder of CMEA Capital; Carol Browner, former head of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency; and Steven Chu, former U.S. Secretary of Energy and now Stanford professor of physics and of molecular and cellular physiology.

A commonly held idea is that the main problem with cleantech was that new energy technologies require much more time and money to develop than do IT startups, with which the investors had much success.

The new analysis dives deeper. Cleantech startup founders and employees usually had extensive experience in areas like inventing new materials and devices, but they often utterly lacked experience in manufacturing or operating a business, the researchers find. A similar lack of experience was not necessarily fatal for information technology startups, because they often were creating new markets, whereas clean energy ventures are trying to capture a share of an existing market.

“The oil companies and utilities that the startups seek to displace are very well-tuned operations,” said co-author Ernestine Fu, BS ’13, MS ’13, MBA ’16, an investor at venture capital firm Alsop Louie Partners. “The good news for cleantech is that an increasing number of managers from traditional energy companies now work at startups, providing much needed knowledge.”

The researchers and the people they interviewed agree that fund managers should not invest in startups that are not ready for commercialization, but they disagree on which types of funds will get the cleantech ball rolling again. Baruch advises that smaller funds should avoid cleantech, because they do not have sufficient capital to survive energy’s long development cycle.

However, Susan Preston, founding general partner of the California Clean Energy Fund’s angel investments, thinks venture capital for cleantech will remain minimal for at least a few more years and that angel investors through typically modest stakes will reinvigorate the market over the next decade.

The role of government

“Today’s cleantech industry is like the early days of ocean exploration,” said Fu. “The monarchs sponsored the early expeditions, which were expensive, very risky and potentially highly profitable. By doing so, they created new trade routes and new markets, and after a while, trading companies and the rest of the private sector took over. The original investments paid huge dividends to their countries.”

In cleantech today, the group agreed that government should not make venture-style investments in companies that are fairly advanced. Instead, if the government wants to spur cleantech, public funds should instead go to research and development of technologies too speculative for the private sector to sponsor. These dollars should be relatively small and spread out among many promising technologies.

The people interviewed also agree that good public policy is key to developing sustainable energy, and they offer a wide variety of policy prescriptions that would help build the market and infrastructure:

- Government should create markets by building demand for clean energy with incentives like taxing greenhouse gas emissions, giving tax credits for energy-efficient vehicles and setting efficiency standards for appliances and lightbulbs.

- Low-interest government-backed loans should be available only to startups that have already eliminated almost all technical uncertainty and achieved low production costs.

- Instead of supporting commercialization of advanced technologies with direct investment, government can support these companies with long-term supply contracts at competitive prices.

- Government should inform investors when a particular technology is ready for commercialization and educate consumers about new options in the market.

As these policies create demand and technologies develop, the cleantech investors can identify strong teams to support.

“Investors can identify talented, bold entrepreneurs in a way that government cannot and should not,” said the third co-author, Justin Bowersock, founder of Rockhill Advisors and a former researcher with Stanford’s Steyer-Taylor Center for Energy Policy and Finance. “An early investment is often a bet on the founder and the team as much as on the technology. This involves a lot of intuition and pattern matching from past experience. No government policy can replicate this process.”

After setting clear goals and ground rules, government should leave the private sector as much flexibility as possible, suggests Browner.

For entrepreneurs, Baruch advises that trying to make energy cheaper is a losing battle for solar companies. Instead, successful U.S. solar companies today are those that provide solar services and finance, rather than manufacture panels. Woolard says that entrepreneurs should first learn what the market wants before developing a new technology.

The work was supported by the Kauffman Fellows Program.