Millennials hope to reach life milestones by the same age as other generations, new Stanford study says

New research from the Stanford Center on Longevity shows that the ideal time for life events, such as marriage and home ownership, has remained relatively constant across generations.

Millennials – young adults in their 20s and 30s – are marrying, buying homes and starting families later in life. But just because they are postponing these major life events does not mean they want to.

A new study from the Stanford Center on Longevity shows that millennials are not intentionally delaying life milestones, such as buying a home or getting married. (Image credit: martin-dm / Getty Images)

Millennials hope to achieve important life goals at the same age as previous generations, including those now in their 60s, 70s and older, according to a new study from the Stanford Center on Longevity.

Researchers found that the ideal timing of major milestones has remained relatively constant across generations.

“Millennials want to achieve the same things around the same time as everyone else,” said Tamara Sims, a research scientist at the Center on Longevity, about the findings of the study, called the Milestones Project.

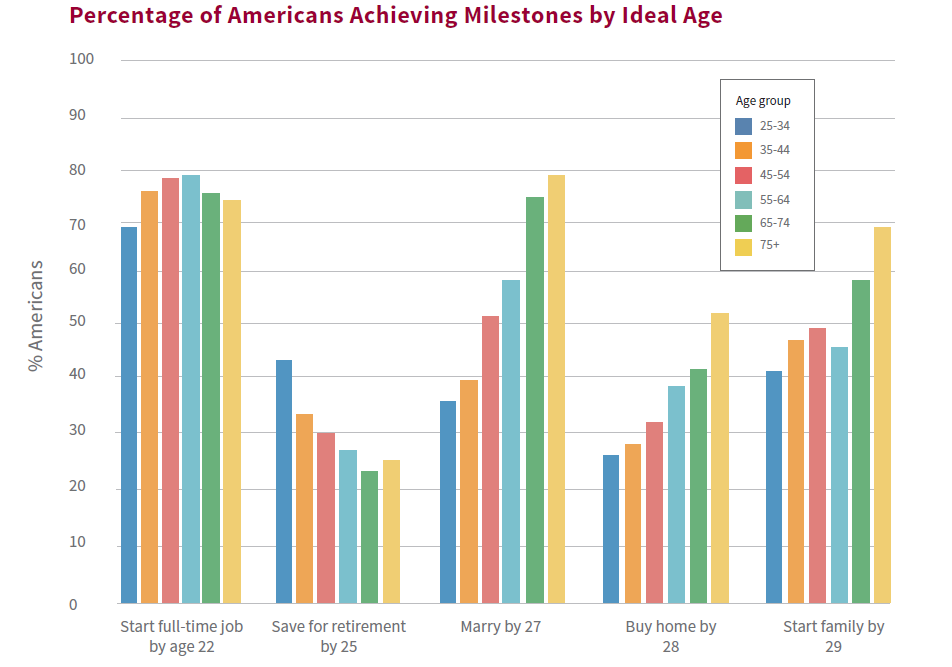

On average, people over 25 said they wanted ideally to marry by 27, buy a home by 28 and start a family by 29. However, the extent to which people reached these goals decreased with every successive generation, with those between 25 and 34 being the least likely to achieve them.

“Our findings suggest that young adults are not the disruptors that they have been made out to be,” Sims said. “They are indeed getting married, buying a home and starting a family later than their ideal age at lower rates than other generations, but this decline did not start with them.”

As part of the project, researchers surveyed four generations – 1,716 participants ranging from ages 25 to 75 and older – to find out when people hoped to attain their goals versus when they actually reached them.

A graph from the results of the study by the Stanford Center on Longevity shows the percentage of Americans experiencing five different life milestones at the ideal age across age groups. (Image credit: Courtesy Stanford Study on Longevity)

The study showed that home ownership was a goal that the fewest number of American millennials actually reached. And millennials are not alone. Researchers found that even those aged between 35 and 54 experience a 7-year difference between when they intended to buy a home and when they did. Those 65 and older reported buying homes only one or two years after their ideal age for home ownership.

In addition, the study showed that millennials want to save for retirement sooner than previous generations, and 43 percent are actually doing so, more than any other older generation did when they were that age. This finding could be attributed to an increase in policies and programs promoting retirement savings in recent years, Sims said.

“Beliefs and values about the right way of doing things – in this case, when you should get married, buy a home – are very ingrained in our culture,” said Jeanne L. Tsai, a Stanford professor of psychology in her comments about the new study. “At the same time, I think the results on saving for retirement are really encouraging. They suggest that with education and alternative models for doing things, beliefs, expectations and even behavior can change.”

Discrepancies between what people desire and what actually happens in their life can reliably predict poorer health and well-being, Sims said about previous research, noting that it is important to track these generational changes and strive to reduce those discrepancies.

“People are appearing to pursue ideals for life that were set around World War II, and it doesn’t make sense that we as a society haven’t questioned these ideals,” Sims said. “We hope this study, along with the center’s broader mission, helps people rethink their goals in this era of long life and empower younger generations.”

The study is the latest effort from the Center on Longevity’s Sightlines initiative to stir conversation about what leads to long, healthy living. Americans have added an unprecedented 30 years to their life spans over the last century, and the center hopes to encourage more policymakers, entrepreneurs and members of the public to think about ways of dealing with an aging population and longer life expectancies.