Earthquake drill strengthens campus response skills and abilities

Some 400 people gathered in more than 20 campus and hospital locations to practice their response to a 7.0 earthquake that, thankfully, did not strike California on Nov. 8. But it could have.

The 7.0 earthquake struck about 7:30 a.m. on election day, Tuesday, Nov. 8, with its epicenter about 5.5 miles northwest of Stanford on the San Andreas Fault.

Shirley Everett, center, senior associate vice provost, Residential & Dining Enterprises, speaks with other administrators at the QuakeSU 2016 exercise in the Emergency Operations Center. (Image credit: L.A. Cicero)

It was a powerful, frightening and destructive temblor, felt throughout campus and the Bay Area. Bay Area downtowns were destroyed, roads and airports closed and a state of emergency declared.

AlertSU messages quickly encouraged Stanford students, faculty and staff to evacuate buildings and head to designated evacuation assembly points. Some people were crying, some were in shock and some were injured. Most remained calm.

Phones were mostly operational, but landlines and cell connections were quickly congested. The university invoked its emergency backup power. The president canceled classes, and research was suspended. Temporary shelters were raised to house students. One faculty member died.

And that was all before the 6.2 aftershock hit.

Only a drill

If you missed that earthquake entirely, don’t worry. It never happened.

Of course, it could have, and that’s why about 400 people gathered in some 20 locations throughout campus Thursday morning to practice how the university would respond to the needs of the campus community should such a powerful earthquake strike.

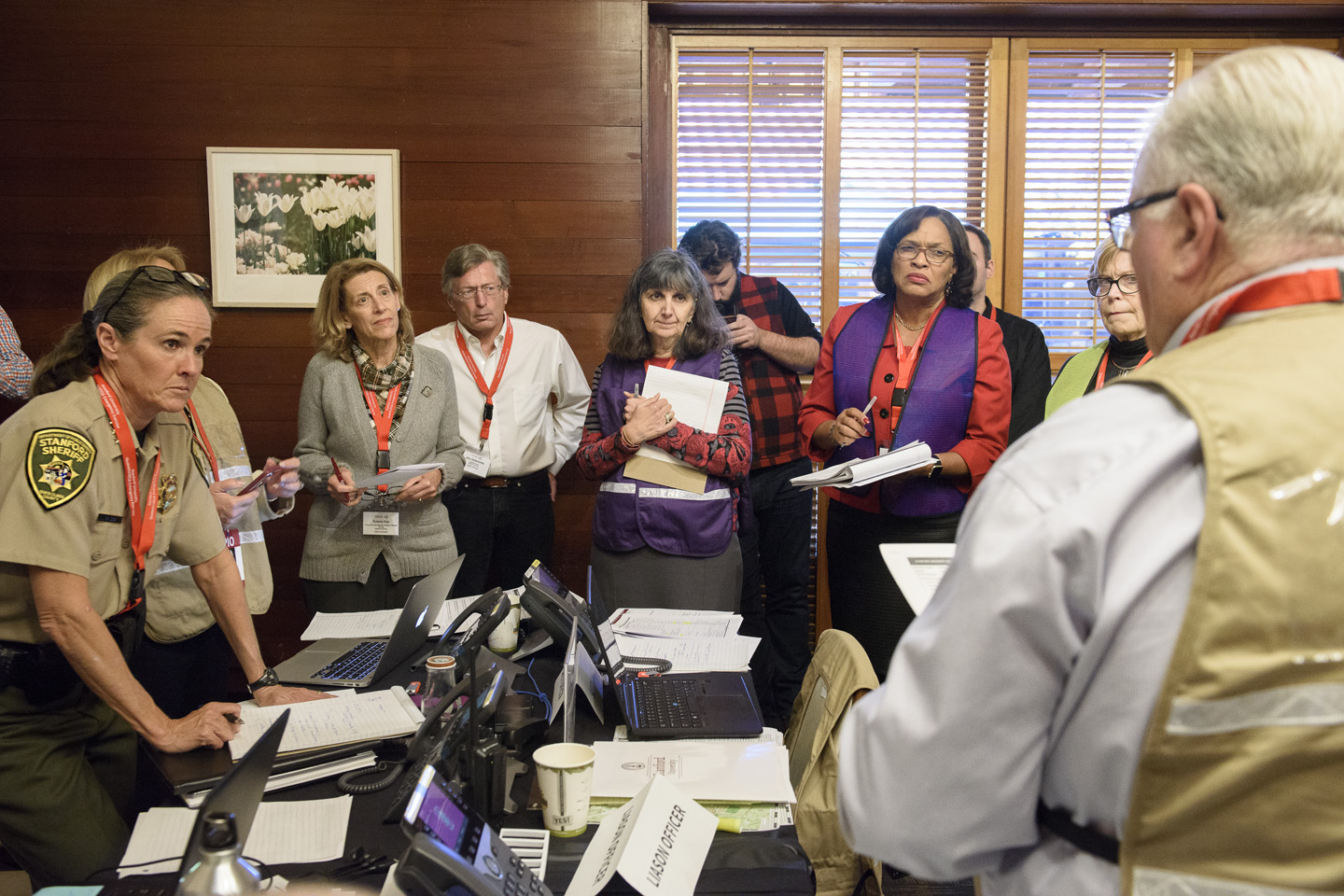

Participants in the Emergency Operations Center listen to Larry Gibbs, right, vice provost for environmental health and safety, as the exercise moves to a close. (Image credit: L.A. Cicero)

The earthquake drill, a year in the planning, involved both university and Stanford Medicine emergency operation centers. The drill allowed for exchange between the two for the first time. The university frequently practices emergency scenarios, but this also was the first drill to focus on actions 48 hours subsequent to the earthquake, rather than during its immediate aftermath.

Thursday’s drill asked responders to consider how they would, for instance, account for everyone on campus. How would Stanford continue to feed thousands of people and provide for sewage disposal in the face of possible damage to the university’s infrastructure? How do you quickly assess the safety of 800 buildings? How do you answer the thousands of people calling the university, concerned about their loved ones?

“We wanted to create an experience focusing mainly on recovery and restoration, rather than the immediate life safety you would experience right after an emergency,” said Keith Perry, university emergency manager and training and communications manager for Environmental Health and Safety.

“It’s a difficult kind of challenge and forces you to look at a completely different set of issues than we have invoked in past drills,” Perry added.

The scenario and actions of participants left an impression on President Marc Tessier-Lavigne after his first emergency drill at Stanford.

“I’m impressed with the preparedness of the team,” he said. “This is a finely honed machine.”

Impressed was also the word used by Police Chief Laura Wilson, whose job was to manage the many people gathered in the main emergency operations center in the Faculty Club.

“I really appreciated the professionalism, expertise and collaboration of everyone involved,” she said. “My job was made much easier by the fact that people practice and know what to do. But the challenge is communications. And that’s something we’ll have to continue to work on.”

Complicated challenges

Most of the morning’s action was focused on the Faculty Club, where participants were grouped into policymakers, including the president, provost and many of the university’s vice presidents; operations leaders, whose areas of concern ranged from health care to housing to finance; and University Communications, which simulated emergency messages alerting and updating the campus community. At Stanford Stadium, which was called the Simulation Cell, participants contributed the probable reaction of external participants, from parents to trustees to politicians. Some 20 local emergency centers participated from schools and departments throughout campus.

Perry, a 20-year veteran of Stanford emergencies, believes that, with each drill performed, responders get better at handling the complexities of issues involved in protecting public safety, ensuring the integrity of the university’s infrastructure and quickly returning the university to normal teaching and research functions.

“After you participate in these drills, you begin to realize the vast and complicated challenges of a distributed day-to-day operational model,” he said. “I think everyone learned a lot today.”