Interdisciplinary thinking: Stanford scholars and students imagine truly ‘human cities’

Through Stanford’s Human Cities initiative, students explore how cities can evolve into places where the focus is on people and sustainable living.

At Stanford, scholars and students are looking for creative ways to make cities better places for people to live and thrive – places that offer quality and affordable housing, desirable public spaces, robust transportation systems, healthy air and water, and economic promise for all.

Go to the web site to view the video.

Great cities foster human relationships and social inclusion, said Deland Chan, a lecturer in urban studies and co-founder of Stanford’s Human Cities initiative: “This is as much about the process of decision-making in designing our cities as it is about technological solutions.”

In the Human Cities initiative, students identify urbanization challenges and then attempt to develop technological, policy and design solutions to them. Though housed within the Program in Urban Studies, the effort is interdisciplinary above all, offering courses and programming open to undergraduate and graduate students from any major, while harnessing faculty brainpower from across campus. The focus is on innovative curriculum, influencing policy and building research networks, Chan said.

“We are drawing from existing and rigorous methods from the fields of engineering, design, planning and architecture. There are existing best case practices and lessons that show a human-centered approach has worked in cities of all sizes around the world,” she said.

An urbanized world

The world is increasingly urban – 2010 was the first year that more people lived in urban than rural areas, and nearly two-thirds of the population is expected to reside in cities by 2030. Eighty-two percent of U.S. citizens lived in urban areas in 2015, compared with 70 percent in 1960, according to the United Nations.

Cities, Chan explained, are complex entities that require interdisciplinary efforts across all walks of life and study.

“Instead of engineers focusing on the infrastructure of cities and social scientists focusing on social networks and practices of a city, we need to create a new global citizen and scholar who is able to navigate across disciplines, across cultures, and integrate elements in a holistic systems approach to cities,” she said.

And now, there is no better moment to address the issue of inclusion in our cities. “Entire segments of urban populations are excluded from the potential that cities have to elevate quality of life,” said Chan.

Urban harmony, collaboration

Sneha Ayyagari, a senior majoring in environmental systems engineering, said the collaborative approach behind Human Cities courses resonated with her goals to “promote harmony between human and natural environments” across different cultures.

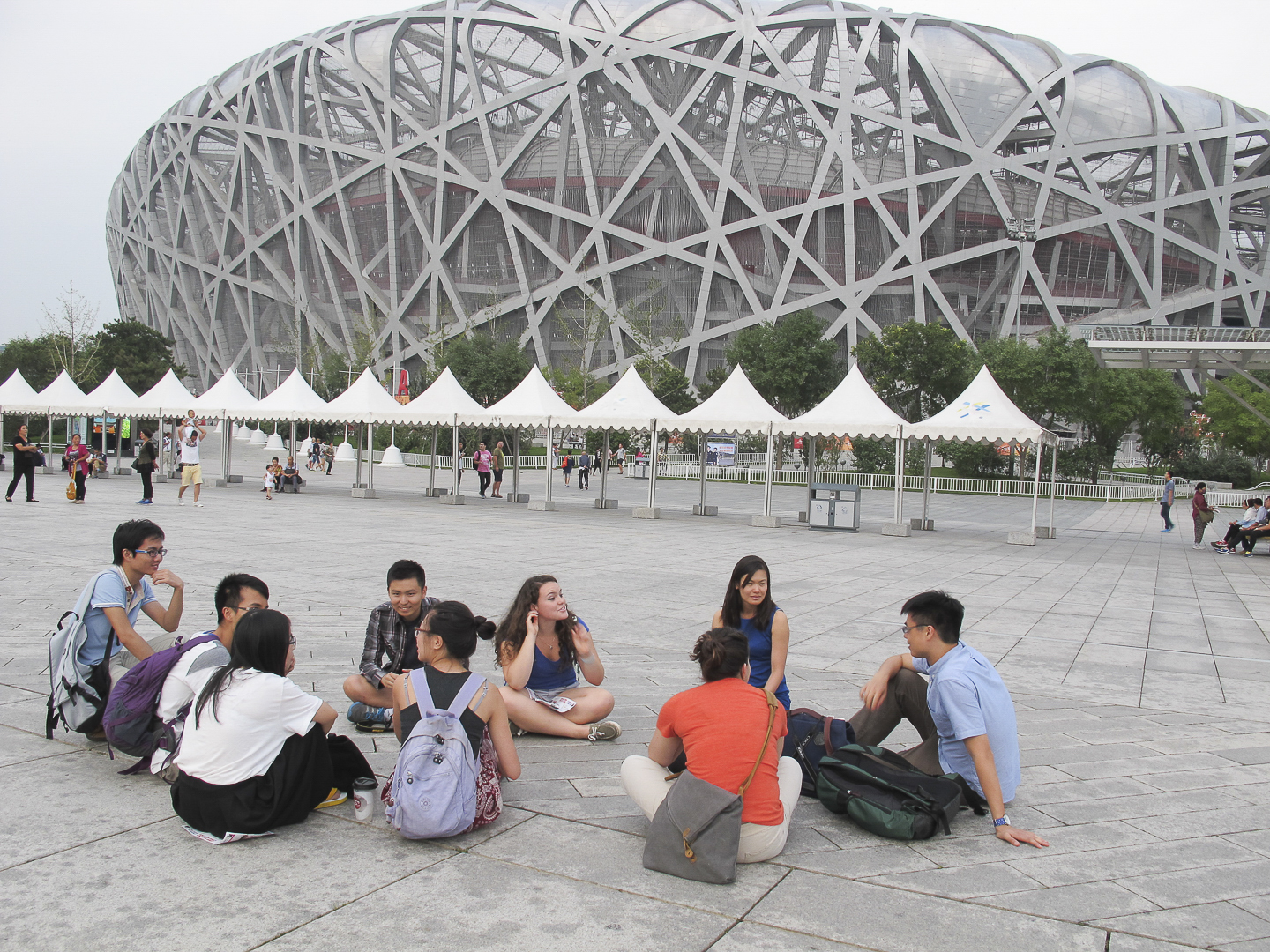

A discussion group meets at Beijing National Stadium, popularly known as the Bird’s Nest, which was constructed for the 2008 Summer Olympics. (Image credit: Linda Ly)

“We learned the importance of respecting local context while working with multinational teams and projects,” Ayyagari said.

She added, “In particular, learning about the interactions between the four pillars of sustainability – environmental quality, economic vitality, social equity and cultural continuity – motivated me to actively seek interdisciplinary teams, spaces and communities to brainstorm integrated solutions to urban challenges.”

Chan said that the initiative draws on faculty and students from all sectors of campus, culminating in an interdisciplinary approach across campus and with organizations beyond.

She noted, “To do this work effectively, we need to build relationships and collaborate.” At Stanford, the initiative has built relationships with the Civil and Environmental Engineering Department and Stanford Arts, among others. And off campus, it has partnered with community groups and corporations. For example, students contributed ideas to planning groups in the city of Belmont and to the San Francisco Bicycle Coalition.

Chan said, “We are not hired by these groups and do not accept monetary compensation. It’s not a consulting or client relationship. Rather, we provide tools and capacity to analyze their work in an objective, analytical manner.”

She said it is an important lesson for the students to listen to the people who live in communities, get feedback on what works and does not work, and then learn how to clearly present findings in public forums and to policymakers.

As a result, it is a “bottom-up and top-down” approach, as Chan described it, to envisioning how metropolises and surrounding regions – like Beijing, the San Francisco Bay Area and Paris – might evolve.

For example, in their coursework on Beijing, students discovered that the lack of open spaces is a huge concern in China’s capital city. And in the Bay Area, the availability of transportation options and the lack of affordable housing are affecting the quality of life.

Experiential learning is key. Now in its fourth year, the initiative offers a Beijing-based studio where U.S. and Chinese students examine sustainable urban development at a human scale. It is part of International Urbanization, a collaboration between Stanford and Tsinghua University in China.

Other courses underway include Defining Smart Cities, cross-listed in Urban Studies and Civil and Environmental Engineering, and an International Policy Studies graduate seminar focusing on the United Nations HABITAT III summit.

‘Living spaces’

Stanford graduate student Caroline Nowacki explained that cities are typically viewed from one perspective, such as that of the architect, planner or engineer, who are considering technical issues and trying to find one optimal solution.

A student conducts fieldwork in Beijing by interviewing a train station guard. (Image credit: He Fan)

“However, cities are living spaces that historically have emerged from collective work and add-ons from individuals more or as much as from the grand design of a planner,” said Nowacki, a doctoral candidate in civil and environmental engineering. “As we design cities of an increasingly large scale and incorporate increasingly complex technologies, the risk of forgetting the ‘users’ of the city increases.”

For students, it is about building a toolbox of analytical skills. As Chan noted, “When students graduate and start working in the field, they’re going to need this toolbox: How do you approach this work in a way that is meaningful, respectful of local context and, most important, effective?”

Nowacki agreed: “How does one with no Chinese language skills interview hutong inhabitants [people who live in narrow alleys in Chinese cities]? I turned my role into an observer of body language, sounds, qualitative and quantitative aspects of the cityscape, and tried to complement my teammates’ skills as best I could.”

Chan co-founded the initiative with urban studies lecturer Kevin Hsu, and they-co-lead the initiative with history Professor Zephyr Frank and urban studies acting director Michael Kahan. She sees the initiative as leveraging Stanford talent to address pressing urban issues on behalf of humanity’s future.

“The key is to develop frameworks that allow students to think globally and creatively,” Chan said, “while respecting local communities and the need to collaborate far and wide.”