Stanford launches digital humanities minor, combining tech skills with critical thinking

A new interdisciplinary minor gives students the opportunity to blend traditional humanistic research with technology tools.

Digital Humanities is a new minor for Stanford undergraduates, combining digital tools with explorations of history, literature and other topics. (Image credit: Stanford University)

By combining scientific and computational methods with interpretative and critical thinking skills, the field of digital humanities opens unprecedented doors to what scholars can achieve.

This burgeoning field is attracting Stanford undergrads.

In addition to taking courses in which they use digital tools, growing numbers of students are also working closely with faculty members on digital humanities projects outside of the classroom, where they apply computational criticism to the study of literature, combine historical and digital analysis to investigate Chinese grave relocations, and develop social annotation tools to be used in teaching online courses, to mention a few.

Many of these projects are conducted in labs at the Center for Spatial and Textual Analysis (CESTA) and in the Stanford libraries.

But until now, there has been no formalized way of acknowledging digital humanities as part of the undergraduate curriculum.

Administered by the English department, the Digital Humanities minor program officially launched in September to fill that need.

“The timing is right for a Digital Humanities minor at Stanford,” said Zephyr Frank, CESTA’s director and one of the four originators of the minor.

Frank pointed to the duality of a growing number of humanities faculty experimenting with digital tools and the unprecedented access students have to technical capacity.

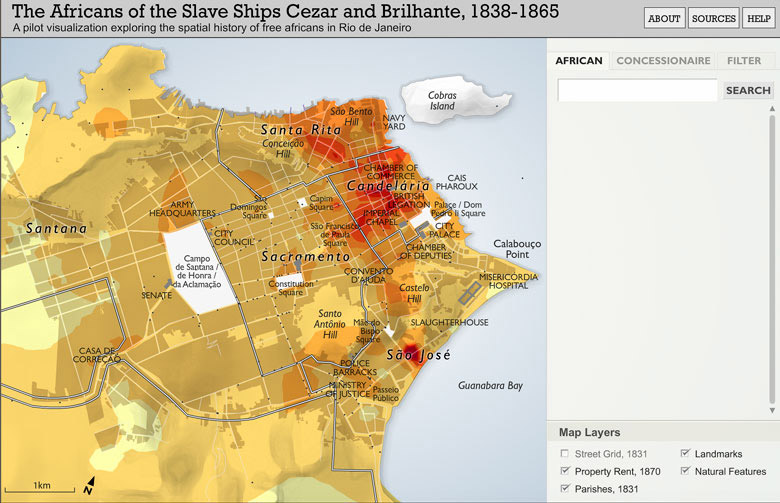

The Broken Paths of Freedom visualizes Africans rescued from a Brazilian-flag slave ship. Click to enlarge. (Image credit: Courtesy Stanford Spatial History Project)

The intersection of faculty research and teaching and student interest and capacity makes DH a natural place to grow and sustain our shared commitment to the humanities at Stanford,” Frank said.

During her freshman year, current sophomore Angelica Previte worked in the CESTA lab on the Nineteenth-Century Crowdsourcing project directed by Sarah Ogilvie, lecturer in linguistics.

Previte, who will likely major in computer science, is one of the first students to enroll in the digital humanities minor.

“It will help me investigate a wider variety of computer science applications than CS department courses alone usually do,” she said. “Computer science courses provide a set of tools and ways of solving problems, and digital humanities provides an opportunity for a more diverse field of uses for those tools.”

Creating new knowledge

Students satisfy the minor requirements by completing six courses within one of three Digital Humanities clusters: geospatial humanities, quantitative textual analysis, and text technologies. The courses are picked from more than 70 offerings that span disciplines as varied as linguistics, history, management science and engineering, and earth sciences.

The program, Frank said, “is distinctive in its embrace of computational methods and simultaneous commitment to humanistic inquiry. Students will learn how to apply these methods now, building skills and critical capacity, while also fostering a durable connection to the arts, literature, and human culture.”

Unlike the existing CS+X joint majors program, the DH minor does not require any computer coding knowledge. Instead, courses in the minor focus on teaching students how to use existing digital tools and methods to expand their research.

Particularly, students in computer science, statistics, or similar technical or scientific fields should look at the DH minor as complementary to their studies.

Mark Algee-Hewitt, assistant professor of English and director of the quantitative textual analysis cluster, said the minor “offers students instructions on how to apply the skills that they already have to humanities data, in such a way as to be responsible to the critical thought that is the hallmark of humanistic inquiry.”

For example, classes in the geospatial humanities concentration draw upon anthropology, geography and other disciplines with a tradition of interest in space in order to teach students how to visualize data from fields like literary studies.

Meanwhile, quantitative textual analysis courses use computers to quantify formal properties of texts, ranging from word frequencies to chapter divisions to character networks.

Text technologies encompasses technologies of communication; social media analysis; database creation, coding, TEI; technologies of publishing and text access; and digital curation of virtual exhibitions.

The hope, Algee-Hewitt said, is to eventually expand the minor to include additional clusters relevant to the field such as digital music studies, game studies and critical code theory, “areas of very active research and teaching at Stanford.”

Like Previte, May Peterson also worked as a research assistant on the Nineteenth-Century Crowdsourcing project. Though already majoring in classics and minoring in medieval studies, the junior is also a minor in digital humanities.

Peterson said she hopes the minor will allow her to “learn the skills I need to carry out humanities research in new ways, and continue to open my mind to new ways of thinking about quantitative and qualitative research. I’ve begun to experience this through CESTA, but want to learn more of those skills through course work.”

Formalizing a trend

The minor was the collective brainchild of Stanford scholars Elaine Treharne, Zephyr Frank, Mark Algee-Hewitt, and Sarah Ogilvie. Together, they realized the need for a formalized digital humanities track for students who were already engaging in this kind of research in their courses.

Treharne, an English professor and the minor’s co-director who also directs the text technologies cluster, said the minor is a way to involve Stanford’s undergraduates in the “innovative, ground-breaking projects” going on at Stanford.

Treharne said she realized that the interest in digital humanities was already present and there just needed to be a formalized program students could engage in.

Although the minor has the word “humanities” in its title, Algee-Hewitt encourages students from STEM fields to consider it as well. “It will be a common ground for both students in the humanities and those in sciences to think together about the advantages and challenges of this new field,” he said.

Sarah Ogilvie, the minor’s co-director and the Digital Humanities Coordinator at CESTA and at the Stanford Humanities Center, pointed to the practical benefits the minor offers. Students will be able to show “they are serious scholars who know technology,” which will be an added bonus on their resumes later on.

Ogilvie said that the intention is for the minor to continue growing in its offerings. Any course in which digital tools are being used can potentially be made part of the minor offerings, and Stanford faculty are encouraged to reach out to add their classes to the growing list of digital humanities courses.